Introduction

Young people face myriad obstacles in finding work, and more than 71 million are unemployed globally (International Labour Office, 2017). Many of these youth have limited job search skills, poor labor market information, and difficulty accessing jobs, obstacles more pronounced for marginalized youth and first-time work-seekers.

Key Findings

Digital professional platforms like LinkedIn can affect the rate at which some marginalized youth find work in developing economies.

New research shows that youth can be taught at low cost to successfully use these platforms.

Education, training, and skills providers should teach digital professional platform use and promote uptake in career guidance and job placement support services.

Governments should consider equity in digital platform access and promote low-cost mechanisms for use of these powerful platforms.

Digital professional platforms may give some youth a more effective way to find work than traditional job search strategies. In this brief, we explore digital professional platform use in developing economies. We then present evidence on low-cost ways to teach youth to use these platforms. We end by drawing policy implications for the education and workforce development field.

The Rise of Digital Job Portals and Professional Networking Platforms

Traditionally, job searching meant checking job boards, scouring classified ads, visiting a career center, or tapping personal networks. The digital age has brought a wider reach of job opportunities into view and at a lower cost. Internet-based job searching is now the predominant form of job searching worldwide (Kuhn & Mansour, 2014). Besides job postings, some platforms allow job seekers to post resumes and maintain profiles, build and bolster professional networks, and read professional news and trends. These types of platforms also allow employers to increase the reach of their job postings and gain information on job applicants.

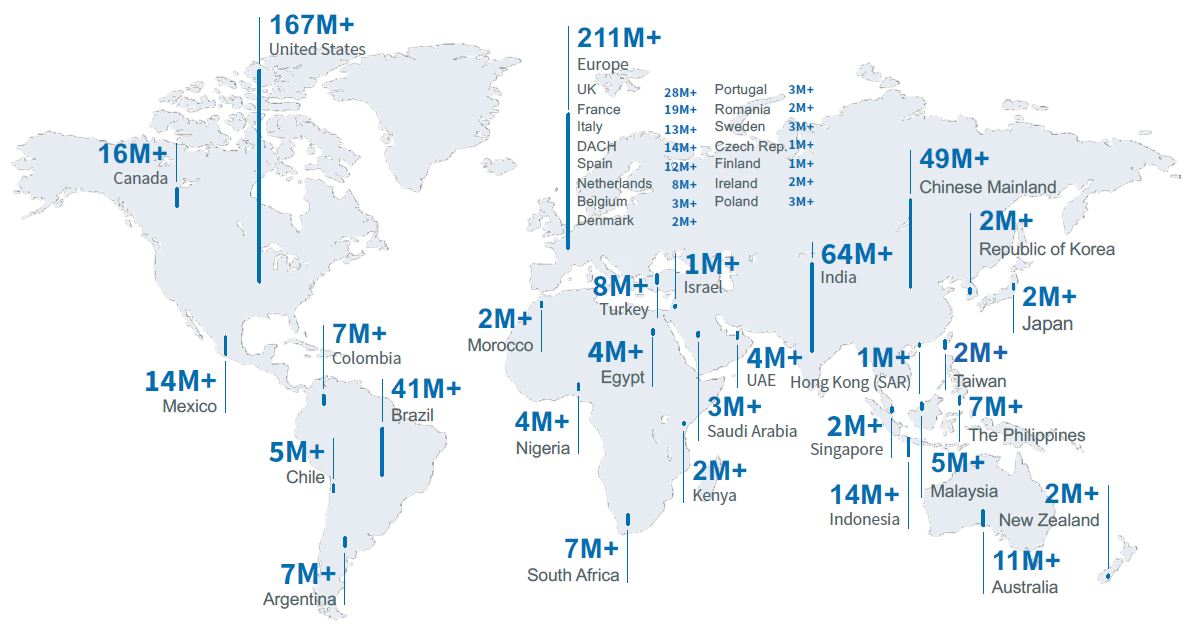

To be sure, access to digital resources is uneven and prone to inequity (DiMaggio et al., 2004), and not all youth may be able to use these job search tools. Yet with more than one million new users coming online each day, more than four billion current Internet users, and three billion social media users, use of these assets is extensive and growing (Kemp, 2019). Worldwide, more than 675 million individuals and 20 million companies use LinkedIn, making it the world’s largest digital professional networking and job-related platform. More than 75% of LinkedIn users come from outside the United States (Figure 1) (LinkedIn, 2020b, 2020a).

LinkedIn envisions a world in which every individual, company, school, and job would be listed on their site, yielding a real-time “Economic Graph” of the labor market (LinkedIn, 2020b). As part of its Economic Graph initiative, LinkedIn partnered with the World Bank to explore trends in youth engagement with its platform (Barbarasa et al., 2017). The study was driven by the following belief:

In today’s digital economy, it is more and more important for jobseekers to have a digital professional footprint through presence on online platforms. Online job portals and professional networking platforms such as LinkedIn can help match youth to jobs and provide a forum to signal skills to prospective employers (Barbarasa et al., 2017, p. 9).

Analyzing data provided by LinkedIn in four large middle-income countries (Brazil, India, Indonesia, and South Africa), Barbarasa et al. found that youth were less likely than more-established professionals to use the platform, with youth under 30 accounting for 10% of LinkedIn users in these markets (Barbarasa et al., 2017). The authors suggested that youth may underutilize LinkedIn because they undervalue both the utility of professional platforms for job searching and the power of professional networking in the job search process, among other reasons.

Among those who did use LinkedIn, younger users were more successful than older users in adding professional contacts and growing their networks (Barbarasa et al., 2017). The authors suggested this could occur because youth have more-advanced digital skills and comfort with forming online connections. Barbarasa et al. recommended that stakeholders “Conduct targeted information campaigns to get more youth to join digital platforms that can connect them to job information, employers, and networks” (Barbarasa et al., 2017, p. 42)

Other recent research suggests this recommendation has merit. In a study of another global online job platform (oDesk), Pallais found that publishing inexperienced workers’ performance on data entry tasks tripled their future earnings on average (Pallais, 2014). In Scotland, use of an online job platform broadened the types of jobs work-seekers considered and the number of interviews they received (Belot et al., 2016). Finally, in another partnership with LinkedIn, RTI International and Duke University researchers, Wheeler et al., found that when disadvantaged work-seekers in South Africa used LinkedIn, they experienced a 10% increase in employment (Wheeler et al., 2019). We explore this study in more detail in the section below.

Supporting Use of Digital Professional Networking Platforms

Wheeler et al. report results on the viability of teaching youth to use platforms like LinkedIn (Belot et al., 2016). South Africa is a useful case for exploring this given its relatively high level of digital connectivity and high youth unemployment.

High Digital Connectivity

In 2018, 31 million people, 54% of the South African population, had access to the Internet (MyBroadband, 2018). A contemporaneous study by Google found that 65% of South Africans over the age of 16 were online (MyBroadband, 2018). This level of connectivity is higher than average for sub-Saharan Africa, a region in which only South Africa has more than half its population online (Pousher et al., 2018). LinkedIn reports 7.1 million members in South Africa, with 288,000 companies on the platform and 264,000 jobs posted in this market (LinkedIn, 2020b). Still, South Africa’s data costs are high. The International Telecommunications Union found that mobile data costs almost three times as much in South Africa as it does in India (International Telecommunications Union, n.d.). South Africa mobile data costs are higher than those in other emerging African economies like Uganda, Kenya, Ethiopia and Rwanda.

High Youth Unemployment

South African government labor market statistics indicate that 52% of total youth 18–34 years of age are unemployed (Statistics South Africa, 2019). Unemployment in South Africa disproportionately affects youth who are black, female, and/or living in a rural area (Wilkinson et al., 2017). A recent study found that the median monthly cost of work seeking among disadvantaged South Africans was $37, about 15% of monthly household income for this group (Graham et al., 2016). As a result, only 22% of a cohort entering the labor market was employed one year later; 50% ended up neither employed nor pursuing further education (Mlatsheni & Ranchod, 2017).

A bright spot in South Africa is Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, a high-performing social enterprise that trains and places youth into employment. To date, Harambee has worked in six urban locations with more than 500 employers to provide 140,000 jobs and income-generating opportunities to a network of nearly 650,000 youth. Generally, applicants are eligible to receive Harambee’s programming if they are between the ages of 18 and 35, have completed high school, come from a disadvantaged background, and have little or no previous employment. Harambee determines disadvantage based on the household income of the applicant, their level of dependency on social welfare, and their education qualification. The Harambee program provides work-readiness training through skills building and behavioral transformation in short courses ranging from three days to eight weeks.

In the Wheeler et al. study, 890 participants from Harambee’s training programs for entry-level jobs in banking, insurance, and business operations were randomly assigned to receive a 1-hour presentation on LinkedIn: what it is, how to use it, and why it might be important to their career progression (Wheeler et al., 2019). Participants in these cohorts also received weekly “nudge” emails encouraging them to join LinkedIn, fill out their professional profile, and grow their professional networks. In-person coaching and discussion sessions supported these nudges. The trainings lasted 6–8 weeks, and the LinkedIn portion cost an estimated $20 per trainee. A second, randomly assigned control group of 748 participations did not receive the LinkedIn intervention but proceeded through Harambee’s typical training program. It should be noted that Harambee students in these banking, insurance, and business operations programs were of higher socioeconomic status, had better education backgrounds, and were assessed as having higher-order cognitive skills than Harambee’s typical student, and likely than other marginalized youth populations in South Africa.

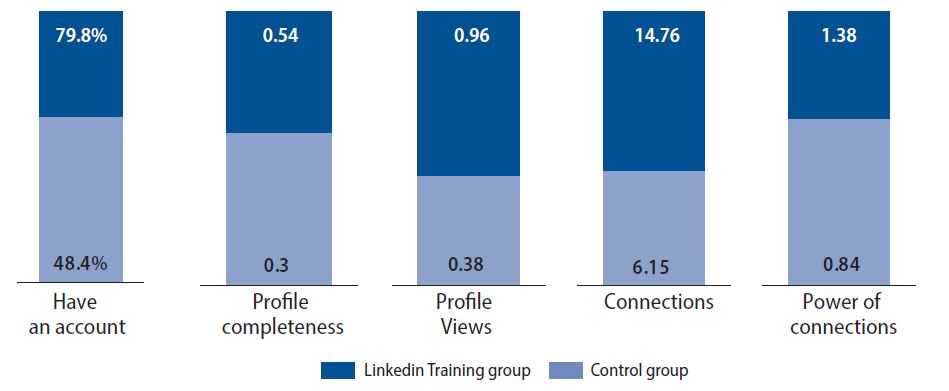

Through an agreement with LinkedIn and with informed consent from the participants, researchers gained access to data on the trainees’ LinkedIn usage (i.e., profile completeness, network metrics, and site usage) at the end of training and at 6 and 12 months post-training. The LinkedIn training had significant effects on both LinkedIn uptake and usage, increasing the percentage of participants with LinkedIn accounts from 48% to almost 80% (Figure 2, bar 1). Compared with participants who had not received the LinkedIn training, those trained on LinkedIn had more-complete profiles (Figure 2, bar 2), were more likely to have their profile viewed by others on the platform (Figure 2, bar 3), had more than twice as many network connections (Figure 2, bar 4), and connections that were more “powerful,” as defined by LinkedIn (Figure 2, bar 5) (Wheeler et al., 2019). Neither the treatment group nor the control group used the platform to view or apply for jobs in any significant way.

Figure 2.

43495LinkedIn uptake and usage factors

Note: Profile completeness is a binary indicator of whether an individual scores above the median in terms of profile completion, calculated by LinkedIn. Profile views are the number of views of one’s profile each month. Power of connections is a measure of the quality of one’s network connections, calculated by LinkedIn based on the education level, professional status, and network characteristics of one’s connections on the platform.

These data indicate that LinkedIn use can be adopted, taught, and improved over a sustained period and at low cost to urban youth such as those who participated in this study. We also know that this training and subsequent platform use matters: treatment group participants gained employment at a 10% higher rate than the control group did (Wheeler et al., 2019).1

The authors conclude that LinkedIn training increases account creation and platform use, which then helps work-seekers convert job applications (made off-platform) into job offers. LinkedIn use likely alleviates either or both of two information failures in the job market. First, the LinkedIn profiles may provide information to firms that helps them to decide which work-seekers to hire. Second, LinkedIn use may provide information to work-seekers that helps them to identify where to apply and to prepare for interviews. It may provide supply-side information that helps work-seekers target their job search and perform well in interviews. Related to both, LinkedIn also may also provide a referral benefit in which firms and work-seekers can tap networks to gain third-party references.

Policy Implications

Emerging evidence indicates that use of digital professional networking platforms matters in easing youth transition to the labor market, but that their rate of use is sub-optimal. The research presented here demonstrates, however, that some young people can be taught to use these platforms at low cost. This evidence has implications for policy, and we recommend the following approaches:

Teach digital literacy and professional networking skills: Youth can be taught digital professional networking skills that aid in job search and labor market transitions. For youth with access to digital resources, education and training providers should integrate digital jobs-platform use into their training curricula, particularly curricula focused on career counseling and job placement. RTI and the Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator developed the curriculum used in the South Africa study and have made it available for open use through RTI’s Global Center for Youth Employment (http://gcyerti.com/projects-publications/projects/). Harambee is extending its LinkedIn training to a wider range of jobseekers. LinkedIn has more than 50 partnerships with training providers that are using LinkedIn in their programs, including Braven, Basta, Coop, Beyond 12, Boys & Girls Club, and Infrastructure Leasing & Financial Services (IL&FS) Skills Development Corporation (LinkedIn, personal communication). For more on the ambitious IL&FS partnership and extension of LinkedIn services into more blue-collar professions in India, see Dubey and Nomura et al. (Dubey, 2017; Nomura et al., 2017).

Reduce data cost constraints: Youth face constraints in using digital services, including the cost and availability of connections, and must make tradeoffs between personal/social and professional services use. To ease these constraints, public and private stakeholders might provide low-cost or free Internet access for work-seekers to use these services during active unemployment periods. For example, the city of Johannesburg mounted a digital literacy and free Wi-Fi campaign called Maru a Jozi. Although that publicly funded initiative has been discontinued, South African youth can still find free Wi-Fi spots through corporate sponsorships like AlwaysOn.

Promote more inclusive and comprehensive digital platforms: Digital solutions must attend to issues of equity. Bias in digital algorithms and in differential access to digital platforms has been well-documented (DiMaggio et al., 2004). So, too, have concerns that platforms like LinkedIn are only relevant for certain job categories and for jobseekers of certain socioeconomic backgrounds. It is encouraging to see the rise of country- or region-specific sites like Lynk in Kenya, Babajobs in India, and Edukasyon in the Philippines, among hundreds of others, that seek to connect work-seekers to a wide range of formal and informal job opportunities across skill and income ranges. LinkedIn Lite and other lower-cost, easier-access services are also a step in the right direction, as is LinkedIn’s effort to extend networks to the underserved (Plus One Pledge) and provide coaching and mentorship services.

Extending access to and uptake of digital jobs platforms is but one way to reduce job search frictions and ease school-to-work transition burdens for young people. The Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Laboratory (J-PAL) recently published a policy brief on a range of interventions that reduce job search barriers (Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL), 2018). The J-PAL review covers transportation subsidies for job searches, career fair vouchers, linking job searches to unemployment insurance, CV and interview workshops, reference letter promotion, job search planning, and increasing the information available to work-seekers and employers via digital job portals. They find that job search assistance for work-seekers, and especially efforts to improve qualifications signaling, are effective in reducing search-related employment barriers, with caveats that some evidence may not translate across all economic development levels.

J-PAL’s review also highlights cases where job search interventions did not work as intended, likely because of other, more-influential mitigating factors like economic downturns (lack of job demand), mobility and migration costs, and mismatches in youth expectations or preferences for certain jobs versus those available and offered. These limitations likely apply to findings and recommendations related to use of digital platforms such as LinkedIn. Any policy response to youth employment also must attend to displacement effects. If the number of jobs is constant or diminishes in times of economic downturn, increasing the job search skills of some may “displace” the employment of others. Policy change includes tradeoffs, including in the case of youth employment.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Laurel Wheeler of the University of Alberta, Robert Garlick of Duke University, and Marissa Gargano of RTI for their collaboration in this research. We also thank Maryana Iskander and staff at Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator and Meg Garlinghouse and her team at LinkedIn for their support.