District Malaria Surveillance Officer Shaabani Khamis visits the home of a malaria patient in the Charawe district of Zanzibar to test her mother for malaria, check on medication, and follow up using the Coconut Surveillance system on a tablet.

In recent years, Zanzibar, a semi-autonomous archipelago that is part of Tanzania, has made huge gains towards malaria elimination. Having a strong malaria surveillance system in place—defined as the people, procedures, and tools to generate information on malaria cases and deaths—is central to a countries’ ability to sustain progress and ultimately achieve elimination. In fact, surveillance systems are so important that the World Health Organization views them as a core malaria intervention.

As countries move toward malaria elimination, the tools for conducting malaria surveillance change. As transmission decreases, as has been happening in Zanzibar, malaria becomes isolated to certain geographic areas, and the intensity and frequency of reporting increases. In these situations, surveillance systems must evolve from reporting aggregate case data by month over large geographical areas (e.g., districts) to reporting near-real-time individual case data in small areas called foci.

RTI has worked closely with the Zanzibar Malaria Elimination Programme (ZAMEP) since 2006 to strengthen its malaria surveillance system, supporting the development of a case-based surveillance system (known as Coconut Surveillance), a mobile software app that district malaria surveillance officers (DMSOs) use on tablets to capture and respond to real-time cases at the facility and household level.

With funding from the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID)-led U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI), we continue this work through the Okoa Maisha Dhibiti Malaria (OMDM)—Save Lives, End Malaria (2018-2023) Activity by promoting integration and local ownership of data systems and strengthening the use of malaria data for decision-making to move Zanzibar and Tanzania closer to elimination.

Here are a few of our takeaways from designing, implementing, and integrating these data systems.

1. Understand the ecosystem

When implementing technology on global health projects, we are big believers in (and endorsers of) the Principles of Digital Development. These are a set of best practices endorsed by 250 organizations for designing and developing digital technology in international development. One of these principles is to understand the ecosystem. To us, understanding the ecosystem means knowing what information systems are already in place and having a sense of the local capacity to use and maintain new systems.

In Zanzibar’s case, the Malaria Early Epidemic Detection System (MEEDS) is the original system that helped health facilities report aggregate case data through mobile phones, enabling ZAMEP to identify epidemic outbreaks within two weeks. In 2012, MEEDS was updated to support individual case reporting, but the malaria officers that would respond to reported cases still needed a systematic way to collect additional information and supply the exact geographic location of the case.

To fill this need, RTI worked with ZAMEP to develop Coconut Surveillance, an app that would run on the malaria officers’ tablets, collect all necessary data when they investigate individual cases, and guide them through an active case response protocol. For all of this to work, this app would need to be easy to use, work offline (as malaria knows no network coverage boundaries), and most importantly would need to be interoperable with MEEDS and the District Health Information Software (DHIS2), the main platform that the Ministry of Health uses to collect all public health data at the national level.

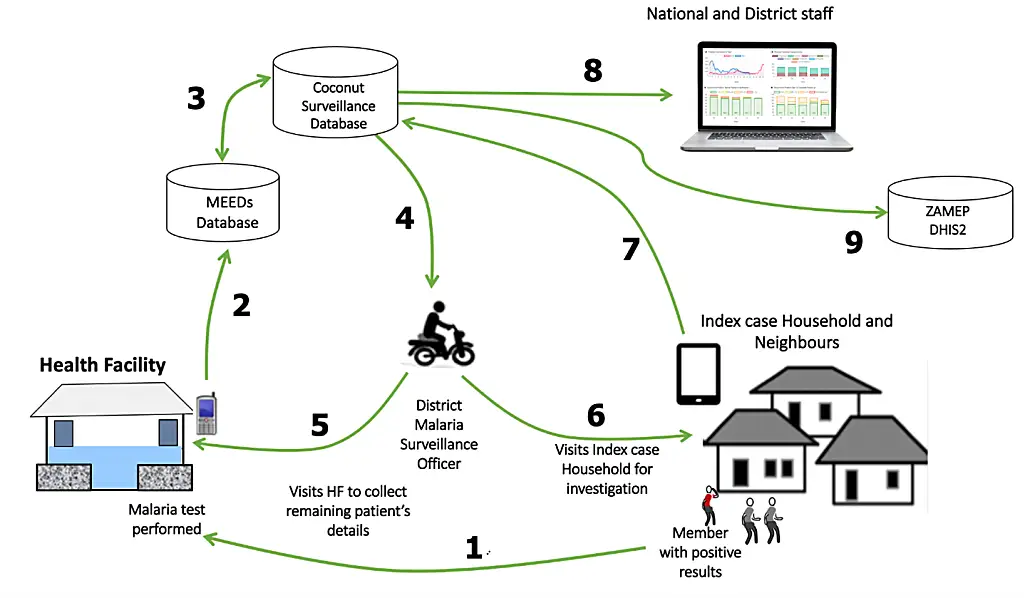

See the figure below for how Coconut fits into the broader malaria surveillance ecosystem in Zanzibar.

The malaria case notification process starts when an individual tests positive for malaria at a health facility. A health care worker at the facility uses a feature phone to record this case by sending a text message to the MEEDS system. This new case is then picked up by Coconut Surveillance to alert the district malaria surveillance officer with a notification on their tablet. They visit the household and are guided through a reactive case response protocol while capturing Geographical Positioning System (GPS) coordinates of the patient’s household. The data are synchronized at least daily with a shared cloud database. Finally, a web-based dashboard enables near real-time monitoring of active follow-up.

2. Ensure interoperability and embrace open data systems

While DHIS2 is the government standard for public health surveillance, it is not able to capture information about malaria cases at the household level. As certain districts get closer to eliminating malaria, a technology like Coconut is essential to collecting information on individual cases, including the use of preventive measures like bed nets and travel history to be able to understand whether cases were locally acquired or whether they are being imported from other countries.

Since not all health workers and decision makers have access to the Coconut database, we knew we needed to ensure that Coconut worked within the broader surveillance ecosystem and was interoperable with the country-owned systems already in place to ensure the seamless transfer of information.

For this reason, we designed Coconut to be an open system that uses the internet to communicate and operates using the same protocol as Zanzibar’s existing surveillance system. Through the USAID OMDM Activity, we are working to integrate Coconut’s data with these existing systems, thereby accomplishing two things:

- First, we are supporting the technology infrastructure that is already in place. By using the MEEDS system, Coconut builds upon investment in the network infrastructure and agreements with Selcom, a local value-added service (VAS) provider. We are also working to integrate Coconut with DHIS2, so that as malaria cases are reported through Coconut, the data are compiled and made available to the DHIS2 dashboards that ZAMEP is already accustomed to using, enabling decision makers to view all data in one place including trends by year, month, and district.

- Second, by integrating with in-country reporting systems, we avoid introducing divergent data in the health information system. In this case, ZAMEP can continue to use their current reporting system for surveillance without having to reconcile data discrepancies, making it easier and less costly to interpret case data and target specific communities where outbreaks are most likely to occur.

Zanzibar District Malaria Surveillance Officers visit a malaria positive household during a training on how to use Coconut. Credit: Michael McCay/RTI International.

3. Build sustainable local ownership

Coconut, like any database, requires constant monitoring and updating to ensure that everything is continuing to work as it should. This requires a very specific skillset. To pass on knowledge and understanding of how to operate Coconut, RTI is collaborating with ZAMEP and the Ministry of Health to train five local staff with ICT backgrounds on how to manage the technology, troubleshoot issues that arise, and make enhancements to the system. This includes developing training resources and a curriculum that ZAMEP can use to continue to train its staff going forward.

By syncing data indicators from Coconut into the broader system and training staff on how to manage the Coconut database and use and interpret the data, we are helping to ensure Zanzibar has the skills and tools it needs to reach elimination.

Learn more about Coconut Surveillance