COVID-induced school closures eroded the learning gains of the last decade. Early grade learning programs have had successes but not the widespread impact many had hoped for. This blog series will answer the question: What will it take to get ALL children learning?

Learning for All

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) committed countries to “ensure that all girls and boys complete free, equitable and quality primary and secondary education leading to relevant and effective learning outcomes” by 2030. Adopted in 2015 by all 191 member states, the SDGs require countries to track 169 targets and 232 indicators, including the percentage of children meeting minimum proficiency levels in grades 2/3, at the end of primary, and in secondary. Both the goal and indicator had an intentional and explicit focus on moving the learning needle for the most children—hoping to unlock the learning potential of millions of children at the bottom of the pyramid.

The new focus on measuring learning in the early grades was, at least in part, spurred by the increased availability of evidence on foundational learning generated by early grade reading and math assessments. The data were alarming. In some countries, more than 90 percent of children enrolled in the second grade could not read a single word. Based on these and other data, the World Bank and UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics estimated that 53 percent of children in low- and middle-income countries could not read a simple story by the end of primary school. In the countries with the least resources, the level was thought to be as high as 80 percent.

COVID has only exacerbated these challenges. Estimates vary, but for those countries where data are available, average learning loss is at least half a school year—with many systems experiencing much more. Many students left the system entirely and may never return. As education systems work to return to a new normal, understanding how to get learning improvement at scale, for the greatest number of students, will be key to recovering from these widespread learning losses.

What We Know About Improving Learning

The good news is that we have a solid body of evidence on how to improve learning. Prior to COVID and in response to growing evidence of low learning levels, Ministries of Education in dozens of countries, supported by donors such as the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and their implementing partners, were delving deeply into the mechanics of improving early grade reading and math. Although teacher professional development had long been a focus of education improvement initiatives, a new wave of efforts focused on developing and delivering structured approaches to teaching and learning. Initiatives included rewriting and redesigning curricula, student textbooks, and teachers’ guides; providing more effective teacher professional development and support; and, in some cases, shifting the language of instruction from a national/colonial language to local languages spoken by the majority of the community. If pre-SDG programs dealt with forest-level issues, programming in the SDG era has been deep in the weeds of evidence-based interventions, including structured pedagogy, to improve learner outcomes.

Many of these programs successfully created tools and approaches that, when used, did improve teaching and learning. A 2018 review of early grade reading programs in low- and middle-income countries showed that programs significantly impacted average reading scores, especially when compared to almost no change in the comparison schools. USAID’s own retrospective on a decade of support for early grade reading showed positive and significant increases in learning in 29 of 42 programs. Nonetheless, while these programs significantly impacted scores, many showed only a small impact in increasing the overall percentage of students scoring well enough to be called proficient readers. What could be the reason for this?

Positive – but Uneven – Progress to Improve Learning

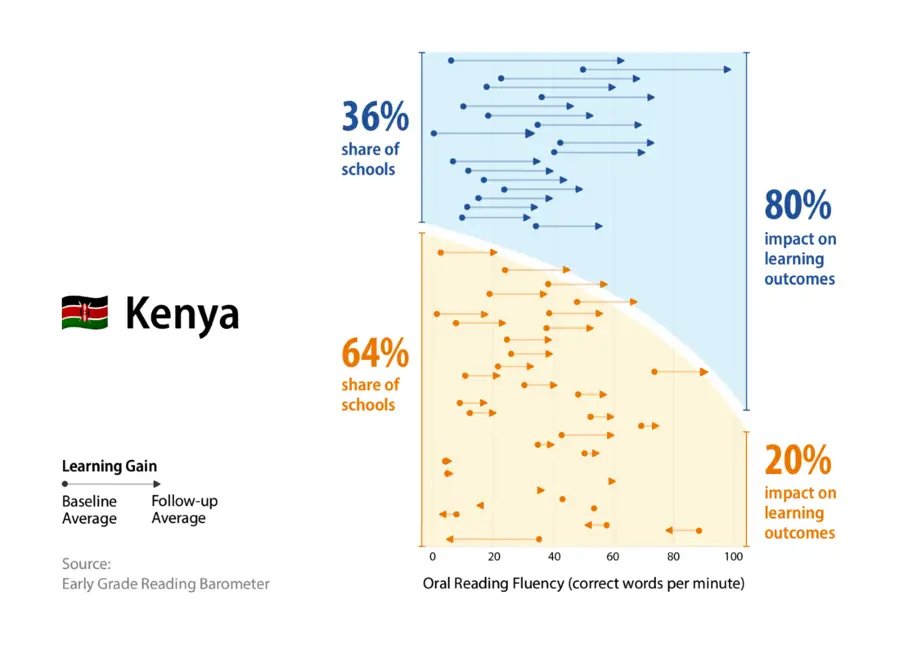

To move learning levels for the millions of students at the bottom of the learning pyramid requires an all-hands-on-deck approach. Yet when we examine individual school-level data more closely, we find that learning gains across schools are not evenly distributed. Rogers’ work on the diffusion of innovation describes how the uptake of new practices differs by group: innovators and early adopters, early and late majority, and laggards. In a study of school-level data from four of RTI’s intervention programs, we find that the innovators and early adopters were responsible for nearly all learning gains. While the average overall impact was significant, the gains were concentrated in a small share of schools.

Data visualization by Julia Chistiakova

For example, in Kenya, 80 percent of the impact was explained by 36 percent of schools. The Kenya graphic above shows the change in average learning outcomes for each school between baseline and follow-up. Each line represents a school. The dot on each line is the school-level average test score at baseline, and the length of the arrow is the total gain/loss in average test score at the follow-up assessment. So, if at baseline, the average score was 30 points and at follow-up, it was 45, the length of the arrow and average gain for that school would be 15. Similarly, if the school average fell from 30 points to 20 points, the length of the arrow and loss for that school would be 10. In this analysis, we use correct words per minute on the oral reading fluency portion of the early-grade reading assessments administered to students in the same schools at two different points in time.

Looking across programs in other countries shows a similar pattern, but with an even lower percentage of schools explaining most of the impact (see graphic below). In Nepal, Nigeria, and Uganda, 80 percent of the impact was explained by just 14-15 percent of the schools.

Data visualization by Julia Chistiakova

How Can Learning Gains Become More Widespread?

We conducted a study in Nepal to better understand why and how these teachers responded to changes within their education systems—in the hopes of replicating their success. We used qualitative methods to explain what is different about the schools that showed significant gains compared to those that did not. In Nepal, we found that successful schools included individuals – teachers, administrators, and community leaders – with positive personality traits such as rationality, empathy, good communication, and the tolerance for uncertainty. These bright spots are exceptions that ignore social norms that create barriers to effective educational change—and aren’t much help in telling us how to motivate change in the rest of the schools.

So rather than focusing on what makes the early adopter schools successful, we decided our effort would be better placed on learning from schools that are not. The opportunity is clear: To unlock the potential of learning improvement programs, we need to focus on understanding what is going on in the underperforming schools—the 64 to 85 percent of schools that do not have much impact on overall learning outcomes. If we can get these schools to implement reading and math programming effectively, we will see learning gains for many more students. This is especially important as systems work to rebuild and recover from learning loss due to COVID.

As Nobel Laureate Daniel Kahneman says, the good way to achieve behavior change is to diminish the restraining forces, not increase driving forces. Thinking about a problem this way is not intuitive, however. We tend to want to focus on the bright spots when we really need to better understand the enabling conditions that can ensure everyone can replicate success.

Using a behavioral science lens, our research team explored how social norms and mental models of teachers and system-level actors influence the response to educational change. At the 2023 Comparative and International Education Society (CIES) annual meeting, we shared these initial findings alongside presentations on teacher norms and behavior change from the World Bank’s Shwetlena Sabarwal and the Research on Improving Systems of Education (RISE) Programme’s Yue-Yi Hwa. In our next blog in the series, learn more about the study, our findings, and conclusions that can help inform the next generation of early learning improvement programs and efforts to recover from COVID-related learning losses.