In 2020, 20 of the 53 new prescription drugs approved by the FDA were related to cancer treatment.1 Drug companies often develop promotional communications to share favorable clinical trial results with oncologists. Some physicians, however, may have difficulty understanding specific clinical trials terms2 or lack the skills needed to properly assess the design, analysis, and synthesis of clinical studies presented in these promotional communications.3

Understanding the difference between preliminary or exploratory data and final clinical trial data is important for assessing clinical utility. In a recent systematic review by RTI and the FDA, physicians with specialized training in biostatistics, epidemiology, clinical research, or evidence-based medicine were better able to appraise studies than physicians with standard medical education and training.3

How Can We Help Physicians Understand Clinical Trial Data?

Prescription drug promotional communications marketed directly to physicians through sales aids by drug company representatives sometimes contain carefully worded claims highlighting data from clinical studies that may exaggerate the benefits and present biased information.5 These sales aids also often include data displays—such as figures and tables—with statistics that may misrepresent or distort data trends and can be easily misunderstood. This could ultimately have negative effects on prescribing decisions.

Prescription drug promotional communications marketed directly to physicians through sales aids by drug company representatives sometimes contain carefully worded claims highlighting data from clinical studies that may exaggerate the benefits and present biased information.5 These sales aids also often include data displays—such as figures and tables—with statistics that may misrepresent or distort data trends and can be easily misunderstood. This could ultimately have negative effects on prescribing decisions.

Strategies could be developed to help physicians understand clinical trial data with uncertain clinical utility and detect results from studies using weak methods. One strategy is to include disclosures in prescription drug communications.

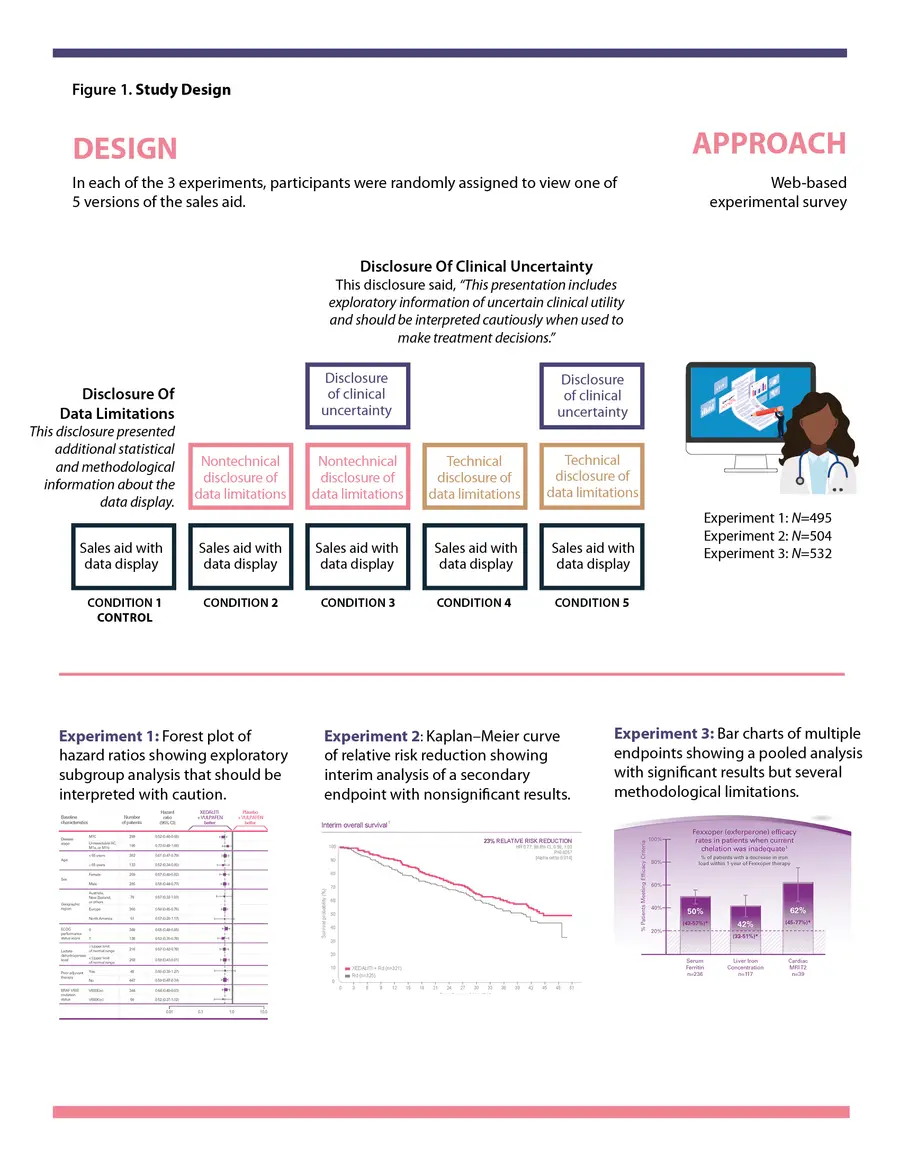

In a recent study published in The Oncologist, we examined two different types of disclosures (Disclosure of Clinical Uncertainty and Disclosure of Data Limitations) presented in conjunction with preliminary or exploratory scientific and clinical data in communications for oncology products.6 In three experiments conducted at the same time, we randomly assigned oncologists and primary care physicians (PCPs) to view 1 of 5 versions of a 2-page sales aid that featured common data displays: a forest plot, a Kaplan–Meier curve, or a bar chart. One version of the sales aid had no disclosure of any kind, which was our control. The other four versions had a disclosure (“Disclosure of Data Limitations”) related to the analysis, results, and limitations of the data. This disclosure used either technical or nontechnical language and was either presented or not, alongside a Disclosure of Clinical Uncertainty. (See Figure 1 for the study design.) We looked at how physicians interpreted these presentations of data with uncertain clinical utility in the sales aids.

In a recent study published in The Oncologist, we examined two different types of disclosures (Disclosure of Clinical Uncertainty and Disclosure of Data Limitations) presented in conjunction with preliminary or exploratory scientific and clinical data in communications for oncology products.6 In three experiments conducted at the same time, we randomly assigned oncologists and primary care physicians (PCPs) to view 1 of 5 versions of a 2-page sales aid that featured common data displays: a forest plot, a Kaplan–Meier curve, or a bar chart. One version of the sales aid had no disclosure of any kind, which was our control. The other four versions had a disclosure (“Disclosure of Data Limitations”) related to the analysis, results, and limitations of the data. This disclosure used either technical or nontechnical language and was either presented or not, alongside a Disclosure of Clinical Uncertainty. (See Figure 1 for the study design.) We looked at how physicians interpreted these presentations of data with uncertain clinical utility in the sales aids.

Can Disclosures Help with Understanding Data Limitations?

Even commonly used data displays can be confusing, and the conclusions physicians draw from them are sometimes unsupported. A prominent and relevant disclosure can help with interpreting data displays by describing caveats and assumptions or directly summarizing key takeaways.

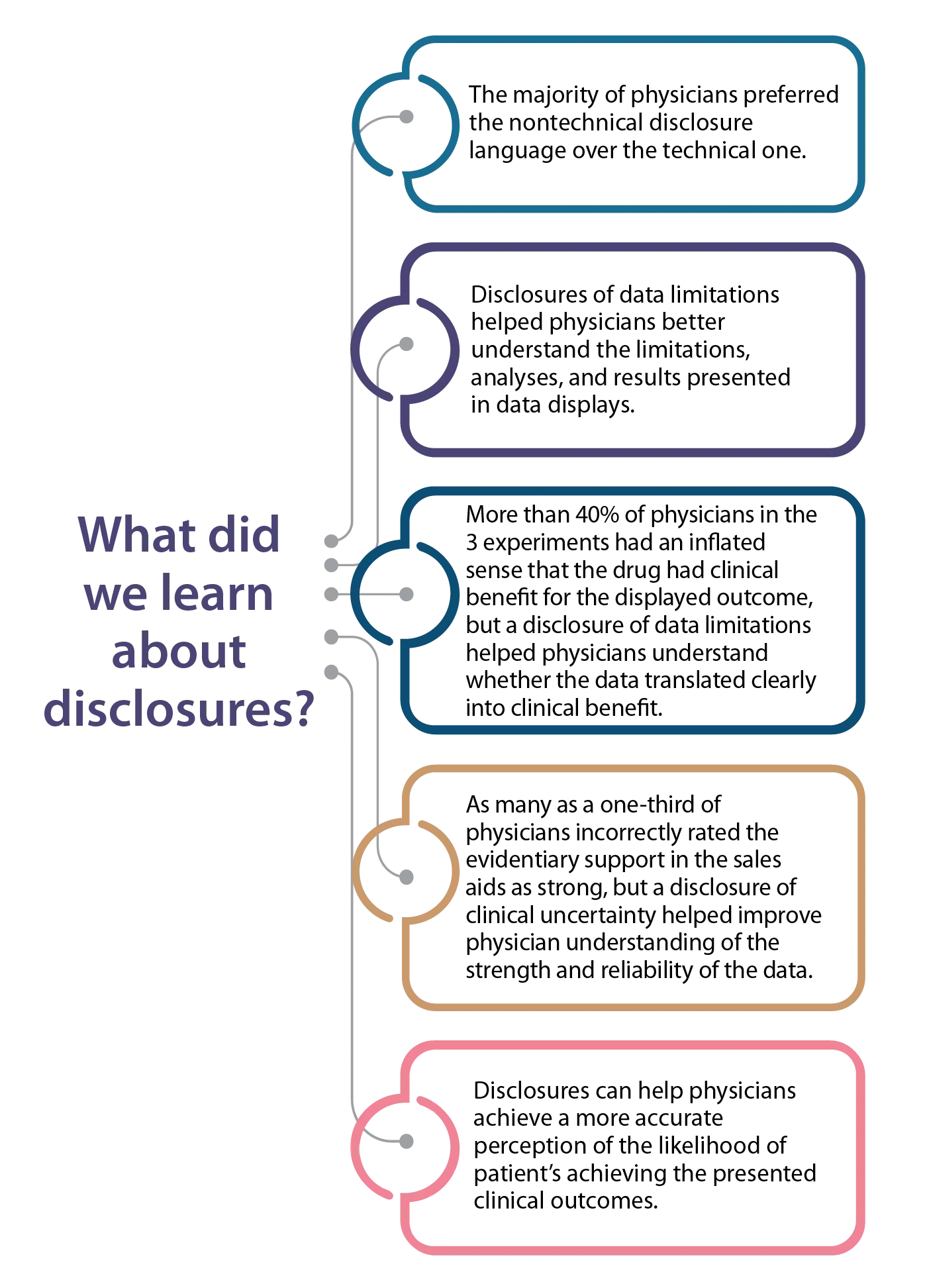

In our study, physicians noticed the two types of disclosures in the sales aids and strongly preferred the nontechnical language for the disclosure of limitations. In some contexts, disclosures can help physicians better understand the limitations, analyses, and results—including the clinical utility of the information—presented in a data display. Importantly, these disclosures never hindered physicians’ understanding.

How data are displayed also may influence the usefulness of a disclosure. In one of our experiments, the only way for physicians to gather some of the important study caveats was through the disclosure. Therefore, disclosures may be particularly relevant when critical information (like limitations of the data) cannot be presented visually in the data display and thus need to be included as a disclosure.

Does Advanced Training Make a Difference?

Physician’s clinical expertise is an important source of information for decision-making. Interpreting clinical trial outcomes may be challenging for clinicians not specifically trained in clinical trial design. We found that oncologists had greater understanding of data displays than PCPs with no oncology experience. Oncologists also were more likely to be familiar with the Breakthrough Therapy designation than PCPs.

We also found that with more oncology experience, physicians were more likely to perceive greater benefits of the drug despite its preliminary or exploratory nature. And we found that experience did not impact attention to the disclosure, time spent viewing the sales aids, or preference for a technical as compared with nontechnical disclosure. These unexpected findings raise the question of why oncologists and PCPs with oncology experience may think that a drug is more beneficial than PCPs without oncology experience.

We also found that with more oncology experience, physicians were more likely to perceive greater benefits of the drug despite its preliminary or exploratory nature. And we found that experience did not impact attention to the disclosure, time spent viewing the sales aids, or preference for a technical as compared with nontechnical disclosure. These unexpected findings raise the question of why oncologists and PCPs with oncology experience may think that a drug is more beneficial than PCPs without oncology experience.

How Can We Improve Understanding Among Physicians?

Data displays and sales aids can be improved to increase understanding and reduce misinterpretation among physicians. One strategy is to include a disclosure in data the display presentation to provide relevant contextual information because, when noticed, disclosures effectively convey information and can help prevent misinterpretations.7,8

Data limitation disclosures also may help physicians understand data with limited clinical utility. In our study, participants exposed to the disclosure of clinical uncertainty and data limitations were less likely to say the data in the sales aid offered strong evidence than participants who did not see a disclosure of clinical uncertainty.6 This may be particularly useful in helping physicians interpret nonsignificant findings or when the disclosure directly addresses limited clinical benefit.

Also, unlike data limitation disclosures, which require tailoring to each data display, the disclosure of clinical uncertainty uses general language that can apply across different types of data displays. We found that in some situations, the disclosure of clinical uncertainty helped physicians accurately interpret the strength of the evidence. More research is needed to establish best practices for using disclosures to convey contextual information in sales aids and other promotional communications.

Unanswered Questions

- Do oncologists have a higher threshold for uncertainty and a lower threshold for data needed to establish whether a drug is beneficial?

- Do PCPs and oncologists have different risk-benefit tradeoffs or have different decision-making processes when deciding whether a drug has clinical utility?

- How common is it for physicians of different specialties and training to encounter preliminary or exploratory data with uncertain clinical utility?

How do Physicians Interpret Regulatory Pathways?

In another study recently published in The Oncologist, we examined physicians’ familiarity and understanding of the FDA's Breakthrough Therapy designation.9 A 2016 study found that physicians believed drugs with this designation were supported by stronger evidence than required by the statute.10 While less common than in the 2016 study, we found that a third of physicians in our study misunderstood the supporting evidence required for this designation. Also, about 6 out of 10 physicians preferred a drug described as an “FDA-designated breakthrough drug” compared with an otherwise identical drug presented as an option in a hypothetical prescribing scenario. Physicians also tend to believe incorrectly that this designation involves automatic qualification for accelerated FDA approval: 6 out of 10 physicians in our study believed this misconception. Future research should examine which medical specialties often treat patients needing drugs that would be released under the Breakthrough Therapy designation and methods that can increase familiarity with this designation.

Next Steps

More research is needed to find out whether physicians have a thorough understanding of the data limitations described in presentations of preliminary or exploratory data and whether physicians understand the FDA regulatory pathway.

Unanswered Questions

- How can we increase physicians' understanding of the Breakthrough Therapy designation?

- Do certain regulatory labels (such as "breakthrough") lend themselves to misperceptions?

Research Team

RTI International Project Team

- Vanessa Boudewyns, PhD

- Ryan Paquin, PhD

- Kate Ferriola-Bruckenstein, BA

- Victoria Scott, MS

U.S. Food and Drug Administration Project Officers

- Amie O'Donoghue, PhD

- Kathryn J. Aikin, PhD

References

- https://www.fda.gov/drugs/new-drugs-fda-cders-new-molecular-entities-and-new-therapeutic-biological-products/novel-drug-approvals-2020

- Moynihan, C. K., Burke, P. A., Evans, S. A., O'Donoghue, A. C., & Sullivan, H. W. (2018). Physicians' understanding of clinical trial data in professional prescription drug promotion. The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, 31(4), 645-649.

- Kahwati, L., Carmody, D., Berkman, N., Sullivan, H. W., Aikin, K. J., & DeFrank, J. (2017). Prescribers' knowledge and skills for interpreting research results: a systematic review. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 37(2), 129-136.

- Windish, D. M., Huot, S. J., & Green, M. L. (2007). Medicine residents’ understanding of the biostatistics and results in the medical literature. JAMA, 298(9), 1010-1022.

- Wick, C., Egger, M., Trelle, S., Jüni, P., & Fey, M. F. (2007). The characteristics of unsolicited clinical oncology literature provided by pharmaceutical industry. Annals of oncology, 18(9), 1580-1582.

- Boudewyns, V., O'Donoghue, A.C., Paquin, R.S., Aikin, K. J., Ferriola-Bruckenstein, K., Scott, V. (in press) Physician Interpretation of Preliminary Data with Uncertain Clinical Utility in Oncology Prescription Drug Promotion. The Oncologist.

- Kelleher, C., & Wagener, T. (2011). Ten guidelines for effective data visualization in scientific publications. Environmental Modelling & Software, 26(6), 822-827.

- Rougier, N. P., Droettboom, M., & Bourne, P. E. (2014). Ten simple rules for better figures. PLoS Comput Biol, 10(9), e1003833.

- Paquin, R.S., Boudewyns, V., O'Donoghue, A.C., & Aikin, K.J. (in press) Physician Perceptions of the FDA’s Breakthrough Therapy Designation: An Update. The Oncologist.

- Kesselheim, A. S., Woloshin, S., Eddings, W., Franklin, J. M., Ross, K. M., & Schwartz, L. M. (2016). Physicians’ knowledge about FDA approval standards and perceptions of the “breakthrough therapy” designation. JAMA, 315(14), 1516-1518.