Groundbreaking outcomes from a new study on seized drug data in Ohio–“ground zero” for the fentanyl overdose epidemic

The Evolving Opioid Crisis and the Rise of Fentanyl

America’s opioid overdose epidemic is evolving so rapidly that it’s been difficult for public health authorities to respond with accurate information in real time. During the first 15 years of the opioid epidemic (1999-2014), semi-synthetic opioid pain killers like oxycodone and hydrocodone were responsible for the majority of opioid overdose fatalities.1 This trend first started to shift in 2008 as the heroin supply and the number of heroin deaths began to increase substantially.2 Then, in 2013, a third opioid mortality wave emerged with the black-market introduction of illicitly-made fentanyl in heroin supply chains.3 Deaths involving fentanyl increased 540% from 2013 to 2016, and in 2017, fentanyl deaths outnumbered deaths from both heroin and prescription opioids.4 Overall, the transformation from a prescription opioid epidemic to an illicitly-made opioid epidemic indicates that it’s no longer accurate to characterize America’s opioid epidemic as a singular crisis.

Instead, the opioid overdose crisis can more precisely be characterized as three distinct, yet interrelated, epidemics:

- a 20-year prescription opioid epidemic that has been showing signs of decline since 2016;

- a rapidly developing heroin epidemic that began in 2008, but which has recently been showing signs of decline, specifically in states east of the Mississippi River; and

- a rapidly escalating fentanyl crisis defined by unparalleled increases in supply, consumption, and associated overdose deaths.

This inverse relationship—between declining prescription opioid and heroin epidemics on one hand and an increasing fentanyl crisis on the other—suggests that fentanyl and its many analogs are presenting new and unknown dangers to people who consume street drugs—most notably, an extremely heightened risk for accidental overdose.

Prescription fentanyl is an effective medication when used in hospital settings such as in pre/post-operative surgery or as pain management for handling cancer-related and end-of-life pain. The drug’s rapid onset and short duration of action as a synthetic opioid pain killer, however, makes its illicit form a dangerous product for non-medical consumption.5 Fentanyl is 50 times more potent by weight than heroin, which is why prescription versions (e.g., Duragesic patches) are measured in micrograms rather than the standard milligram measurement. Ethnographic research with people who inject heroin and fentanyl has shown that several grains of fentanyl (visualize grains of salt) is toxic enough to put ‘a heroin-tolerant but fentanyl naïve person’ into overdose.

Unregulated (read: illicit) drug markets obviously lack the regulatory capacity necessary to protect consumers. As a result, fentanyl’s swift ascendency has contributed to an increasingly dangerous opioid overdose risk environment characterized by rapid market fluctuation, inconsistent product availability, and severe variations in purity and potency.6 This kind of rapidly evolving risk environment bodes ill for overdose prevention efforts because product changes within the illicit drug market occur quickly and often well-before consumers can comprehend and adapt.

There is thus a considerable, scientific need to understand how best to investigate the association between transformations in the street opioid market and opioid overdose risk. Our recent publication—Associations of Law Enforcement Seizures of Heroin, Fentanyl, and Carfentanil With Opioid Overdose Deaths in Ohio, 2014-2017—on JAMA’s Open Network platform is an attempt to jump-start this research.

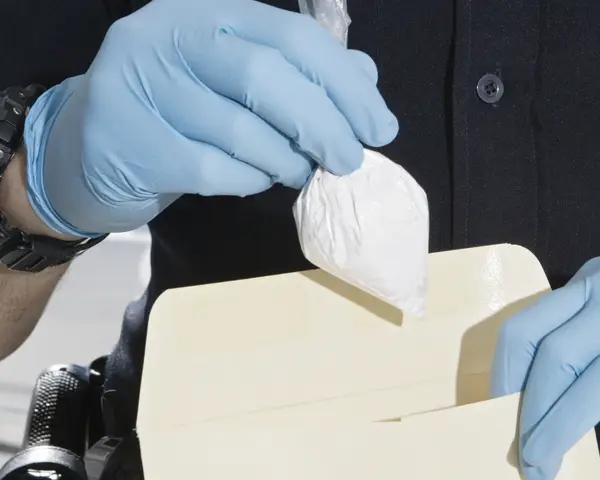

Seized Fentanyl is Shown to Be Significantly Associated with Opioid Overdose Deaths

Our study found that in Ohio, from 2014-2017, fentanyl seized by law enforcement was significantly associated with opioid overdose deaths, thus establishing crime lab data as a useful predictor and potential early indicator of emerging opioid overdose deaths. This main finding further underscores the need to initiate or expand data-sharing partnerships between public health and public safety organizations to address the overdose crisis with more detailed and timely drug testing data.

In addition, the study shows that testing street drugs at the community level (e.g., onsite at syringe services programs) with the same rigor and qualitative instrumentation as state crime labs, can provide similar data to law enforcement seizures, but more quickly and closer to real time. This data could then be used to inform a community-based, early warning system that can help identify drug market changes and strengthen the pinpointing of geographic areas vulnerable to escalating overdose outbreaks.

Currently, however, state and federal public health agencies do not see testing illicit drug supply as a valuable form of surveillance. Even with thousands of fentanyl deaths per year, public health agencies have yet to incorporate product testing of street drugs as a systematic means to determine levels of “contamination” in the market. During, say, a national outbreak of e-coli in the nation’s lettuce supply, ‘testing the lettuce’ is administered as a common-sense approach to determining a pathogen and source contamination. So why is this tactic not deployed within the opioid crisis? We believe our findings from Ohio illustrate the benefits of testing the illicit drug supply for fentanyl and other new emerging psychoactive substances (NPSs), with a particular focus on heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Our paper also contains a number of findings that were not discussed in the JAMA Research Letter due to limited space. This post, therefore, is meant to offer supplementary insights on several of these ‘secondary’ findings, which may help us better understand the scale of fentanyl adulteration in the United States, given that Ohio is ground zero for the current fentanyl epidemic. What follows, then, is my interpretation of how we can identify the “known unknowns” associated with the present fentanyl crisis, while increasing scientific knowledge to confront fear-based myths circulating around this topic.

Our study found that in Ohio, from 2014-2017, fentanyl seized by law enforcement was significantly associated with opioid overdose deaths, thus establishing crime lab data as a useful predictor and potential early indicator of emerging opioid overdose deaths.

Fentanyl Adulteration of Heroin May Be Occurring Further Down the Supply Chain

When investigating the increase in seizures of ‘heroin’ in Ohio from 2014-2017, we found the percentage of those containing fentanyl or carfentanil increased from 3.4% in 2014 to 48.6% in 2017. While we discussed this increase in the paper, there was not sufficient space to discuss the patterns within the increase—specifically related to their weight categories. Here, we discovered that most of the increase across all three years involved seizures weighing less than 30 grams (note: 28 grams = 1 ounce). This finding suggests that the heroin seized in Ohio during the height of the state’s fentanyl crisis (2014-2017) was not likely adulterated with fentanyl during production, but instead, somewhere during distribution (ergo, after it enters the U.S.).

The logic informing this hypothesis derives from the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) reports that identify the kilogram as the most common weight in which heroin, fentanyl, and cocaine are trafficked. From this trend, it becomes possible to infer with some confidence that fentanyl and carfentanil were likely combined with heroin further down the supply chain, quite possibly when kilogram packages got broken down into ounces for distribution to individual sellers.

Similarly, we discovered that the percentage of seizures containing fentanyl weighing less than one gram also increased substantially over this same time period, from 3.5% in 2014 to 52% in 2017. Because it’s likewise known that packages weighing one gram or less are intended for low-level sellers or individual consumers, the increase in this weight category strengthens the former assertion that fentanyl is being mixed into heroin further down the supply chain. More broadly, the sharp increase in consumer-sized packages (<1g) of fentanyl-adulterated heroin from 2014 to 2017 represents the growth on the supply-side that led to the sharp increase in fentanyl consumption, overdose, and death within Ohio’s fentanyl epidemic.

Heroin That Does Not Contain Fentanyl is in Sharp Decline in Ohio

For the last several years, when visiting cities and towns across the country, one consistent pattern I’ve found in both urban and non-urban settings has been the sharp decline in heroin that does not contain fentanyl or fentanyl analogs. One component of my ethnographic research in central and western North Carolina is to categorize the type of street drugs that people are selling and consuming. Through my interaction with low-level sellers and local consumers, I have been able to gather evidence and document the steep decline in Colombian-sourced, brown powder heroin—the type that has dominated North Carolina since the early 1990s—and how this change has affected consumers’ use patterns and health outcomes. This declining trend is consistent with a recent report in the New York Times aptly titled, In Cities Where It Once Reigned, Heroin is Disappearing (NYT, Health Section, May 18, 2019), which notes:

Heroin’s presence is fading up and down the Eastern Seaboard, from New England mill towns to rural Appalachia, and in parts of the Midwest that were overwhelmed by it a few years back. It remains prevalent in many Western states [as Black Tar Heroin], but even New York City, the nation’s biggest distribution hub for the drug, has seen less of it this year [2019].

We found a stunningly similar pattern in Ohio: heroin seizures that did not contain fentanyl or carfentanil decreased consistently from 2014-2018. Heroin-only seizures hovered around 550 in 2014, then started to fall steadily through 2017 before settling under 200 seizures in 2018. It is important to note that the decline in heroin-only seizures in Ohio over this 4-year period occurred as fentanyl-adulterated heroin seizures inversely soared. The reasons for this are many, but our study empirically demonstrates that the increase in fentanyl supply and consumption is occurring in the context of a heroin market in rapid decline.

Fentanyl Adulteration of Cocaine and Methamphetamine is Occurring; Follows Similar Weight Patterns to Heroin but Drastically Less Extensive in Scope

There has been increased concern lately that cocaine and methamphetamine are being adulterated with fentanyl. Adulterating illicitly made stimulants with illicitly made fentanyl introduces opioid overdose risk to people not expecting it, which is increasingly relevant since the U.S. is witnessing a surge in the number of illicit stimulant consumers.

Having the ability to detect when and where adulteration is taking place is critical because the population who are knowingly consuming both opioids and stimulants together—whether blending them together in a cooker to perform a single injection, such as a speedball (opioids + cocaine) or goofball (opioids + methamphetamine), or using them at different times over the course of a day—are more likely to have some level of tolerance compared to people who only consume stimulants without taking opioids. The latter population is larger in number and considerably more susceptible to fentanyl toxicity since they are more likely to be opioid-naïve (read: no opioid tolerance), and thus at much higher risk for opioid overdose. It is therefore critical for public health surveillance to capture whether, and to what extent, cocaine and methamphetamine are being adulterated with fentanyl and fentanyl analogs so we can tailor and target overdose prevention to stimulant consumers who do not knowingly consume illicitly-made opioids.

In Ohio between 2015-2017, we discovered a higher percentage of cocaine seizures that contained fentanyl/carfentanil compared with the smaller number of methamphetamine seizures that did. Most notably, the weight patterns for both coke and meth were similar to heroin, with most of the adulteration occurring in seizures weighing less than one gram. This weight pattern similarly suggests that fentanyl adulteration of coke and meth is occurring at distribution points near the end of the supply chain because, like with heroin, the packages were confiscated in weight classes intended for local markets (>1g and <30g) or individual consumers (<1g). Even so, the key difference between patterns of heroin adulteration and patterns of coke and meth lies in the percentages of packages in each weight class that contained fentanyl.

In 2014 and 2015, there were relatively no percentages listed for cocaine seizures weighing more than 1 gram that contained fentanyl/carfentanil, and the recorded percentages for seizures weighing less than 1 gram were nominal for both years, with 0.5% in 2014 and 0.6% in 2015. Things started to change slightly in 2016 with a relatively higher percentage of cocaine seizures that contained fentanyl or carfentanil (<1 g=2.7%; >1 g and <30 g=0.9%; >30 g=0.6%). There were additional increases in 2017 but they mainly inhabited the <1 g (7.1%) and >1 g and <30 g (3.8%) categories.

Adulterating illicitly made stimulants—such as cocaine and methamphetamine—with illicitly made fentanyl introduces opioid overdose risk to people not expecting it, which is increasingly relevant since the U.S. is witnessing a surge in the number of illicit stimulant consumers.

The Urgent Need for Quantitative Drug Checking via Gas/Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry

A significant limitation of the current study concerns Ohio’s use of qualitative testing methods to check confiscated substances. Qualitative methods are valuable because they reveal the plethora of substances present in any particular drug sample. Comparable to infectious disease surveillance, identifying toxic pathogens in street drug products in near-real time is critically important to track and monitor the trends and patterns of drugs in the illicit market, including the use of geographic information to detect distribution patterns. While qualitative testing methods can satisfy these surveillance demands, they are unable to determine how much of a particular substance is in the sample.

Obtaining proportions and calculating potency requires liquid or gas chromatography in addition to mass spectrometry. This combined technology can differentiate active drug (e.g., heroin) and adulterants (e.g., fentanyl) from inactive diluents (e.g. noscapine) and cutting agents (e.g., caffeine). Because state crime labs in Ohio use qualitative methods only, they could not determine the proportions of fentanyl/carfentanil within a sample in relation to proportions of heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine. As a result, we were unable to establish whether fentanyl adulteration of stimulants was intentional. For example, was the increase of fentanyl adulteration in seizures the result of unintentional trace contamination, or were local sellers intentionally mixing in fentanyl as a response to competition in the marketplace and the perceived need for ‘unique’ and ‘stronger’ products?

It’s reasonable to presume that fentanyl was intentionally combined with heroin, since both are opioids and fentanyl can effectively increase heroin’s potency or be used as a replacement for a diminishing heroin supply. But putting fentanyl in meth and coke? Well, that’s another matter altogether. From all my years interviewing people who consume illicitly made drugs like heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine, I have never once—not once—met a person who injects speedballs or goofballs and prefers to have sellers (and not consumers themselves) determine how much of each drug is included. People who inject opioids and stimulants concurrently via a single injection are extremely concerned with, for example, the proportion of cocaine vs. heroin in their speedball; because even a little misstep or miscalculation can turn a cocaine ‘rush’ into a heart attack or an opioid-induced ‘nod’ into respiratory depression. Consequently, the claim that sellers are intentionally mixing fentanyls into coke and meth and selling a combined product to unwitting consumers is circumspect.

Employing Occam’s Razor as a guide, the more likely scenario is that sellers, in the process of dividing ounces (< 30 grams) into consumer-sized packages (<1 gram), are mixing heroin with fentanyl on the same surfaces where cocaine and methamphetamine are packaged, but without cleaning off the ‘contaminated’ surfaces. This theory has been referred to as ‘the sloppy dealer thesis’ and maintains that fentanyl adulteration of illicit stimulants is, for all intents and purposes, the result of unintentional trace contamination. Another plausible explanation is that local entrepreneurs who have, for a lack of viable and legal employment options, decided to sell drugs are inexperienced and ignorant to the fact that consumers prefer to have control over the type and amount of drugs used in combination injections. These local entrepreneurs turned drug sellers could also hypothetically be trying to distinguish their product from other local sellers by mixing drugs together to create a “better” and “stronger” product, oblivious to the fact that most (if not all) consumers do not want them combined beforehand, or that they may even die because of it.

However, until we can confirm the proportions of fentanyl/carfentanil within a sample, these are all simply hypotheses. Being able to identify the various amounts would help determine the motive for mixing these drugs together and would help craft tailored prevention efforts and messaging on both the seller and consumer side. With the steady rise of the fentanyl crisis across the country, the importance of incorporating liquid or gas chromatography and mass spectrometry into drug testing confiscated substances is crucial to finding these answers.

Conclusion: Insights and Outcomes from a Landmark Study

For the past few years, Ohio has been at the deadly center of the fentanyl epidemic. This landmark study has given us the opportunity to gather extensive insights and draw groundbreaking conclusions to help combat the fentanyl, and broader opioid, epidemic. Most notably, this study confirmed that crime lab data of seized drugs can be used as a predictor and potential early indicator of emerging opioid overdose deaths. We found that seizures of heroin-only (i.e. not containing any fentanyl) drugs are on the decline, while fentanyl adulterated seizures are on the rise. Fentanyl is 50 times more potent by weight than heroin, and with an unregulated illicit market pushing this drug, these seizures correlate to the rise we’ve seen in fentanyl overdose deaths. This correlation calls for deeper data-sharing partnerships between public health and public safety organizations to address the overdose crisis with more detailed and timely drug data.

In addition, this study has led us to a number of secondary conclusions and insights. We have determined, based on the weight categories of the seized heroin, that the drug was most likely adulterated with fentanyl after it entered the U.S. during distribution, as opposed to during production. The findings were similar for fentanyl adulterated cocaine and meth, which is of escalating concern due to the rise in stimulant users in the U.S. who could have a lower opioid tolerance, and therefore, be more susceptible to a fentanyl overdose. However, without being able to test the toxicity amounts of fentanyl compared to heroin, cocaine, or meth through quantitative drug checking, we cannot confirm whether the adulteration is unintentional or intentional. Determining whether suppliers are including fentanyl as a result of careless cross-contamination or by intentionally trying to differentiate their product could have a drastic impact on prevention efforts for addressing the fentanyl epidemic.

For more information on this study, see the JAMA Research Letter and learn more about RTI’s extensive work to help combat the opioid crisis.

About the Author

RTI expert Jon E. Zibbell, PhD, served as the Lead Author for the “Associations of Law Enforcement Seizures of Heroin, Fentanyl, and Carfentanil with Opioid Overdose Deaths in Ohio, 2014-2017" study, published in JAMA Open Network. Dr. Zibbell conducts behavioral and community-based epidemiological research on risk factors and health outcomes associated with the opioid epidemic and injection drug use. He is a medical anthropologist with two decades of field experience in the areas of injection drug use, opioid use disorder, drug overdose, and injection-related infectious disease.

References

1 Rose A. Rudd, Noah Aleshire, Jon E. Zibbell, Robert M. Gladden. Increases in Drug Overdose Deaths—United States, 2000-2014, MMWR: Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 2016 January 1; 64(50-51):1378-82

2 Rudd RA, Seth P, David F, Scholl L. Increases in drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths—United States, 2010–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2016; 65:1445–52

3 O’Donnell JK, Gladden RM, Seth P. Trends in Deaths Involving Heroin and Synthetic Opioids Excluding Methadone, and Law Enforcement Drug Product Reports, by Census Region — United States, 2006–2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2017; 66:897–903

4 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/09/02/upshot/fentanyl-drug-overdose-deaths.html?_r=0

5 Marinetti LJ, Ehlers BJ. A series of forensic toxicology and drug seizure cases involving illicit fentanyl alone and in combination with heroin, cocaine or heroin and cocaine. J Anal Toxicol 2014; 38:592–8

6 Drug Enforcement Administration, US. 2016a. National Drug Threat Assessment 2015. Washington DC: US Department of Justice