When I start to analyze data for a study, part of me always hopes there is some clear-cut answer that doesn’t have to be qualified in any way, that I can make a blanket statement without any nuance. The truth is always messier and more complicated, as the data I analyze are from the real world, representing real people and real places. As an epidemiologist on the U.S Agency for International Development’s (USAID) Act to End NTDs | East program, I have both the challenge and the opportunity to find some significance and meaning amidst often complex neglected tropical disease (NTD) data.

Two years ago, I was asked to work on an analysis of lymphatic filariasis (LF) survey data. Spread by mosquitoes, lymphatic filariasis is a parasitic disease that causes thread-like worms to develop in a person’s lymph system. Left unchecked, the adult worms can lead to fluid buildup in the limbs and genitals, causing disability and often leading to stigma and economic hardship. Treatment of whole communities for at least five years can lead to such a successful drop in prevalence that treatment campaigns can stop. But sometimes districts show protracted progress, “failing” pre-Transmission Assessment Surveys (pre-TAS), the first step in the process for assessing LF elimination. The question was why?

When we started to see a handful of districts failing their pre-TAS for LF, we knew we wanted to look deeper. When I first started analyzing this data, I was still fairly new to the field of NTDs and learning the many interconnected things that make LF elimination possible. Treatment of whole communities at risk for the disease may sound relatively simple at first glance, but the reality is that it’s actually rather complex. Sometimes people aren’t home, or they have migrated to other areas for a few months, other times they aren’t willing to be treated, fear side effects from taking medicines, or feel like they are healthy so they don’t need to take the medicines. There are other aspects that could impact elimination as well, like vector and parasite dynamics, along with some environments being more suitable to transmission.

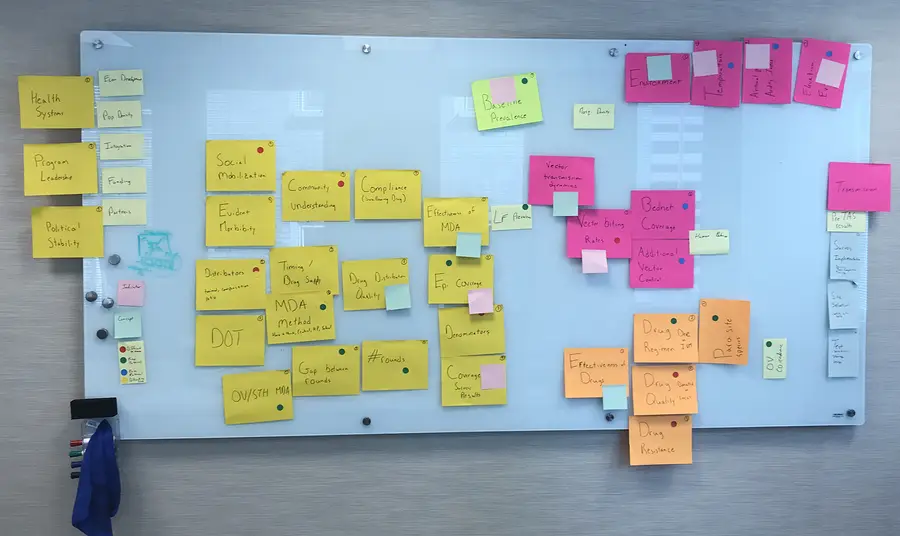

The aim of this analysis was to bring together not only data from 13 countries funded through USAID’s NTD programs but also geospatial data from external datasets. There were a lot of potential variables. In fact, I had them all stuck up on my office wall as individual Post-It notes for several months in hopes of creating of conceptual framework that would help explain what was going on. Everyone who came by to visit me commented on them, and I tried to explain, but ultimately ended up saying “It’s complicated.”

The results? In a recently published journal article in PLOS NTD, Risk factors associated with failing pre-transmission assessment surveys (pre-TAS) in lymphatic filariasis elimination programs: Results of a multi-country analysis, we were able to identify two key variables that contributed to failure in our dataset: high baseline and lower elevation. In many ways, these results are anticipated – more LF transmission to start with means a bigger job to eliminate the disease and lower elevations are home to more mosquitoes.

Even still, it’s complicated. Overall, we had a small number of failures in our dataset, only 74 out of 554 districts observed (13 percent). This is good news for the global program to eliminate LF, but not great news for data analysis as a low number of failures adds some complexity to a multi-variable analysis. Looking just at a more simple single variable analysis we saw a number of variables associated with failure. In addition to higher baseline prevalence and lower elevation there were use of the Filariasis Test Strip as the diagnostic test, primary vector of Culex mosquito, drug combination used, higher population density, higher Enhanced Vegetation Index, higher annual rainfall, and six or more rounds of treatment.

While there is no simple answer to the question “Why do pre-TAS districts fail?”, this first-ever multi-country analysis of pre-TAS data provides insight to risk factors and some areas for considerations if we are to achieve our global goals to eliminate LF. Armed with the knowledge that elevation matters, we can inform decisions on size and shape of survey units, helping to allocate continued resources where they are needed and stop treatment in other areas that may no longer be at risk for LF. So too, the impact of high baseline prevalence helps national programs plan ahead and allocate resources to ensure high coverage and sustain additional rounds of treatment in areas most at risk. As we move toward global LF elimination, these types of analysis become increasingly important to help us in finishing the job, narrowing in on some of the hardest-to-answer questions and often some of the hardest-to-reach populations.

Today, as we work on determining how and when to resume NTD activities due to COVID-19, this analysis can help us understand districts or regions that might have a special risk of failure in the future due to program stoppage. The answers are complicated and depend on lots of information, but we can also say that this analysis has strengthened the evidence base available to inform program design, helping NTD programs get closer to elimination, one survey at a time.