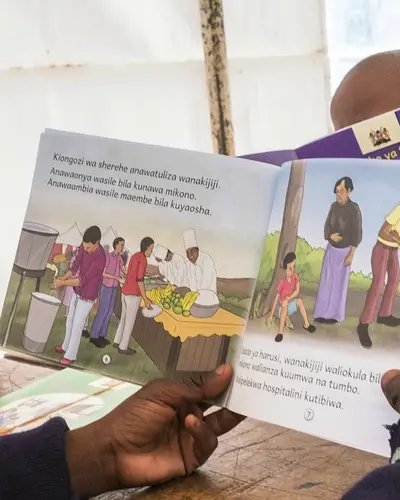

Results-driven international development solutions for a more prosperous, safe, secure, and resilient world

Our Work in International Development

International development focuses on improving the human condition through tested solutions that save and improve lives, drive economic growth, and advance stability.

RTI's International Development Advantage

RTI International is both a global research institute and a leading international development organization. We combine powerful international development capabilities with those of our partners to co-create results-driven solutions for a more prosperous, safe, secure, and resilient world.

Our trusted approach—working with clients, partners, and the private sector—delivers effective and efficient programs that produce measurable outcomes.