Introduction

By agreeing to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the global community set a bold, shared vision to end poverty and improve human welfare. The SDGs, as well as the preceding Millennium Development Goals, have prompted substantially increased investment in development. From 2000 to 2016, US government foreign aid more than doubled from $25 billion to $53 billion, with health programs attracting the most funding (USAID, 2021). Yet progress toward the global goals has been mixed, particularly in health where advances against prominent diseases such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV have been celebrated, but major challenges remain, including access to quality care and sustainable financing.

Key Findings

Research has shown that effective governance enhances social sector investments, yet little evidence exists on the results of integrated development programming that intentionally combines governance and sectoral investments.

This quasi-experimental study of an initiative in Senegal shows that integrated governance is associated with some improvements in health service delivery, specifically some aspects of access and quality at health facilities.

The findings-that health facilities are more likely to be open seven days a week, with higher quality infrastructure and staff following correct procedures, after integrated governance treatment-suggest that integrated governance adds value by improving health service readiness.

We posit that capacity-building of local governance bodies and an emphasis on social accountability could explain the added value of integrating governance and health programming.

As the global community has searched for novel ideas and innovations—technology solutions, private sector partnerships, alternative financing—something more foundational has emerged as a promising avenue for advancing the goals: closer integration between governance and sectoral interventions. As defined by international development donors (USAID, 2013; World Bank, 2017) and researchers (Kaufmann et al., 2009), “governance” encompasses the institutions and interactions through which authority is exercised in a given context, including the selection and monitoring of leaders; capacity to establish and implement policies, services, and programs; and the inclusive involvement of relevant stakeholders (e.g., governments, citizens, and community groups) in decisions (Kaufmann et al., 2009; USAID, 2013; World Bank, 2017). Research has shown that effective governance can enhance sector investments (Brinkerhoff, 2000), including economic growth (Acemoglu et al., 2014), education (Dahlum & Knutsen, 2017), and health (Wang et al., 2018), and that it can be an important condition for achieving the SDGs (OECD, n.d.).

Some donors, such as the US Agency for International Development (USAID), have prioritized integrated programming (USAID, 2013), intentionally combining governance and sectoral investments in strategic collaboration to boost outcomes in specific contexts (Brinkerhoff & Wetterberg, 2018). Yet, integration at the programmatic level has often proven challenging in practice (Falisse & Ntakarutimana, 2020; Francetic et al., 2021). Even when sectoral and governance investments are combined, limited empirical evidence exists on the results of integrated governance on service outcomes, hampering further adoption of integrated program designs.

This brief provides new evidence by interrogating what value an integrated governance approach adds to health service readiness and delivery using data from a quasi-experimental study in Senegal. The study contributes to an emerging body of research examining governance and sector program integration, including recent or active studies in Malawi (Hodel & Dasgupta, 2019), Democratic Republic of the Congo (Comacho et al., 2020), and Guinea (USAID, 2020). We find that integrating governance and health programs can enhance access to and quality of health services, and we explore pathways that link good governance to these service readiness improvements. The remainder of this brief lays out the Senegalese context and research design, presents our findings, and draws implications for future integrated governance programs and research.

The Case of Senegal

Improving health outcomes (SDG 3) is a policy priority but remains a challenge for the Government of Senegal (Ministère de la Santé et de l’Action Sociale, 2018). SDG monitors have noted Senegal’s moderate health improvements, but flag significant remaining issues (Sustainable Development Solutions Network, 2019). In the Senegalese health system, local health facilities range from village-level health huts to commune-level health posts and department-level health centers (The Primary Health Care Performance Initiative, 2019). Health huts deliver basic primary care and a minimum package of family planning, maternal, and child health services, supervised by health post staff. Service range and facility sophistication increase at posts and centers (Devlin et al., 2019).

In Senegal’s decentralized governance structure, local governments (communes) play an important role in improving healthcare because they have been delegated overall management of the budget and specific government, regulatory, and service provision responsibilities. However, communal planning and budgeting for health services are often unresponsive to community needs. Facility budgets are frequently driven by funds earmarked by the central government and routinized budget management rather than by local priorities and the actual costs to provide needed services (Gilbert & Taugourdeau, 2013).

Realizing this untapped potential for local governments to improve healthcare, USAID concurrently funded the Governance for Local Development (GoLD) [2016–2022] and the Integrated Services and Healthy Behavior Adoption (Neema) [2016–2021] programs and mandated they work together in targeted regions, with the assumption that the governance investment would add value to the health program outcomes.

Neema worked in seven regions to promote a community-based approach to increasing access and use of quality health services (Figure 1). Activities included investing in health facilities and the health workforce and engaging Health Local Committees (comités de développement sanitaires; CDS) in facility monitoring and accountability. The CDS, made up of community members, elected officials, and facility staff, educates community members, promotes citizen participation, and monitors service quality and management.

Figure 1.

72725Activity regions for Neema + GoLD and Neema only

Source: Adapted from NordNordWest - Own work, using United States National Imagery and Mapping Agency data, World Data Base II data, Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie Sénégal. Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0

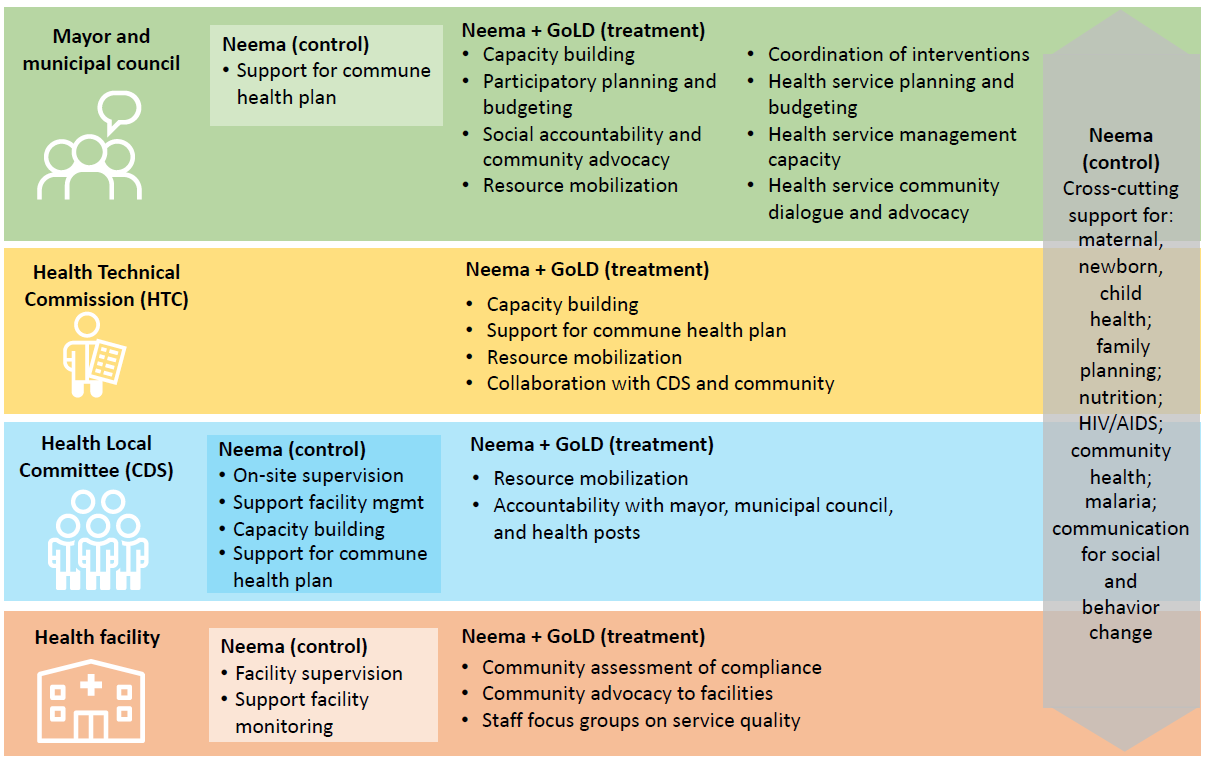

GoLD collaborated with Neema in four regions (Figure 1) using an integrated approach to improve the capacity of local governments to provide priority services by strengthening skills and processes for planning, budgeting, community involvement, and resource mobilization (Figure 2). In line with the recognized need for a multilevel approach to improving service delivery (Bailey & Mujune, 2021; Halloran, 2021; Wetterberg et al., 2016), GoLD supports Municipal Councils and their technical working groups, such as Health Technical Commissions (HTC1), charged with defining and monitoring local health policy, as well as CDS. The regions in which Neema is active without GoLD form the control group for our study of the integrated governance treatment (Neema + GoLD).

Figure 2.

72726Summary of Neema (health-only/control) and Neema + GoLD (integrated/treatment) interventions

Figure 2 shows the specific Neema-only (control) and Neema and GoLD (treatment) interventions at mayor and municipal council, HTC, CDS, and facility levels. The smaller, shaded boxes show interventions that Neema implemented in all communes. The larger horizontal bars show interventions that Neema and GoLD coordinate to implement in treatment communes. Thus, the horizontal bars, including boxes, represent the entirety of integrated interventions in treatment communes; the boxes represent health-sector activities occurring in control communes. Figure 2 underscores the substantial additional integrated activities at the municipal and HTC levels in treatment communes.

Research Design

This research seeks to determine what value the integrated governance approach adds, compared with the health interventions alone, operationalized as three research questions focused on health service readiness and delivery:

Does an integrated governance approach improve the level and/or sources of funding available for commune-level health services?

Does an integrated governance approach improve commune-level health governance functions?

Does an integrated governance approach improve health service delivery?

We took a quasi-experimental approach to assess the effect of integrated governance treatment in the 50 communes where Neema and GoLD worked together—compared with 60 statistically matched control communes within the same regions that received the health program alone (Neema only)—on health service delivery.

First, to select our study communes, we calculated propensity scores for all available communes (50 treatment and 98 possible control communes within the four regions) based on 13 covariates,2 then matched treatment and control communes based on overlapping propensity scores and data collected in the selected 110 communes. Second, after data collection, we applied a 1:1 Mahalanobis optimal matching procedure, which balances covariates exactly, to ensure similar baseline values among matched communes, increasing precision and power. This two-step matching allowed us to isolate the added value of integrated programming within the parameters of ongoing implementation by removing bias and comparing as similar locations as possible among treatment and control communes.

Working with a Senegalese field research team, we surveyed 659 respondents (110 municipal councilors, 110 HTC councilors, 229 CDS members, 83 health hut staff, 101 health post staff, 26 health center staff) in 110 selected communes in the Kédougou, Kolda, Tambacounda, and Sédhiou regions. The surveys, primarily made up of closed-ended questions, were conducted in March 2020.

The survey collected data on health service readiness and delivery dimensions:

Health resources: reports of health service funding levels, sources, and changes. No secondary financial data were available for triangulation.

Functionality of health governance bodies: whether HTCs and CDSs were established, performing expected functions, identifying service delivery issues, and addressing identified issues. Questions were developed based on the GoLD program approach and European Centre for Development Policy Management Capability Framework (Keijzer et al., 2011).

Health service delivery: short-term service delivery dimensions for availability, access, use, and quality at health facilities (note that this research does not gauge patient outcomes such as mortality and morbidity). Drawing on health service frameworks from the World Health Organization and the US Department of Health and Human Services, and input from health experts, we define service delivery dimensions as follows (Table 1). Availability gauges provision of health services and staff. Access relates to patients’ ability to take advantage of available health facility resources. Use indicates patients’ actual utilization of services. Quality is measured by staff competencies, compliance with professional norms, and available infrastructure (US Department of Health and Human Services, 2016; WHO, 2010). Survey questions corresponding to each dimension were drawn from the 2017 Senegal Demographic Health Survey (Agence National de la Statistique et de la Demographie, 2018).

Table 1.

72727Health service readiness and delivery dimensions and subtopics covered in survey

| Dimensions | Subtopics |

|---|---|

| Availability | |

| Access | |

| Use | |

| Quality |

The reported results reflect multivariate statistical analysis of our survey data with separate logistic regressions for different health facility levels (health huts and health posts; regressions do not include health center data due to the small number surveyed) and different health governance bodies (HTCs and CDS).3 For brevity and clarity, we represent statistically significant results as predicted probabilities, calculated from regression coefficients. Predicted probabilities express the likelihood of a certain outcome occurring. Across these analyses, we only report statistically significant findings.4

Does Integrated Governance Enhance Health Service Readiness and Delivery?

Our analysis shows that integrated governance is associated with improvements in some health service readiness and delivery dimensions in Senegal. Specifically, we found statistically significant evidence of improvements in some aspects of access and quality at health facilities in treatment communes compared with control communes in the areas below. There were statistically significant differences in only a subset of variables gauged in the survey. However, taken together, they indicate a higher level of general service readiness in treatment communes (WHO, 2010).

Access

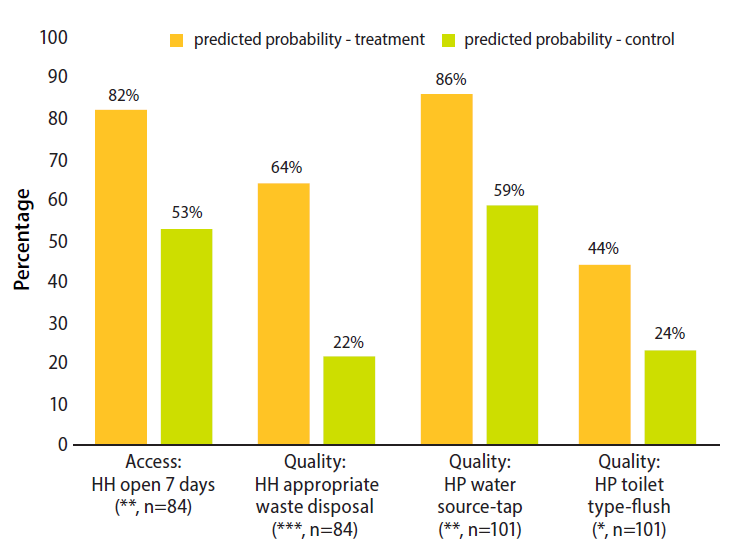

Health huts in treatment communes are more likely to be open (accessible) than health huts in control communes. On average, the predicted probability (likelihood) of a health hut in treatment communes being open 7 days a week is 82 percent, compared with 53 percent for control communes (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

72728Predicted probabilities for health service delivery variables by treatment/control communes (using average values for standard controls)

Notes: HH = health huts; HP = health posts. Asterisks indicate levels of statistical significance for treatment variable coefficient in regressions using dependent variables on x-axis.<br>* p < 0.1<br>** p < 0.05<br>*** p < 0.001

Quality

Compared with control communes, health huts in treatment communes have more community health officers on staff (an average of 1.2 community health officers vs. 1 in control commune health huts; regression coefficient significant at p < .1 level.). This means that treatment health huts more frequently had more trained, qualified staff members. Treatment commune huts are also more likely to dispose of waste correctly (64 percent predicted probability compared with 22 percent for control, Figure 3). Health posts in treatment communes are more likely to have higher quality infrastructure (tap water and flush toilets) than those in control communes. Treatment health posts have an 86 percent predicted probability of having higher quality tap water source and a 44 percent predicted probability of having the higher quality flush toilets (Figure 3).

The study did not find statistically significant differences in availability or use of Health Hut or Health Post services in treatment and control communes, nor in access to Health Post services.

How Does Integrated Governance Add Value to Health Service Delivery?

The study also suggested some possible mechanisms for how integrated governance might contribute to better health service delivery.

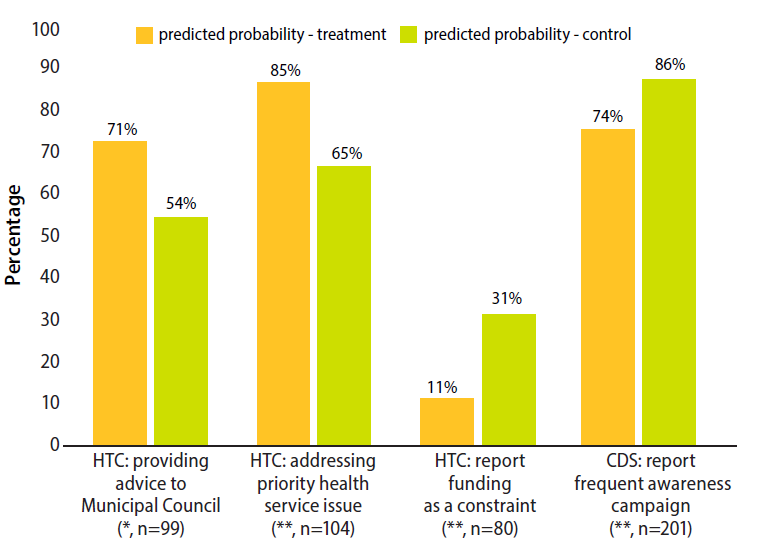

Treatment communes have better functioning HTCs that are more actively addressing health service problems. HTCs in treatment communes more often self-report providing advice to the Municipal Council (predicted probability 71 percent for HTCs in treatment communes, compared with 54 percent for controls; Figure 4) and addressing health service delivery issues in their commune5 (predicted probability 85 percent in treatment communes, compared with 65 percent for controls). These results suggest that HTCs exposed to integrated governance interventions are more actively working to improve health service delivery by engaging municipal decisionmakers and taking direct action to resolve problems. Furthermore, HTCs in treatment communes are less likely to report funding constraints (predicted probability 11 percent in treatment communes, compared with 31 percent for controls).

Figure 4.

72729Predicted probabilities for HTC and CDS functionality by treatment/control communes (using average values for standard controls)

Note: Asterisks indicate levels of statistical significance for treatment variable coefficient in regressions using dependent variables on x-axis.<br>* p < 0.1<br>** p < 0.05<br>*** p < 0.001

There was only one statistically significant difference in CDS performance between treatment and control communes. A higher percentage of control commune CDSs report conducting an awareness campaign in the last year (predicted probability 74 percent in treatment communes, 86 percent in control).

Implications for Health Care in Senegal, Program Design, and Achieving the SDGs

The study findings demonstrate that an integrated governance approach—combining health sector expertise with support for governance structures at community, facility, and municipal levels—has a positive association with some indicators important in health service readiness and delivery. Statistically significant evidence of improvements in several measures of access and quality dimensions at health facilities in treatment communes indicate a higher level of service readiness.6 These measures—showing that health facilities are open more, with higher quality infrastructure and staff more likely to follow correct procedures after integrated governance treatment—could illuminate one link in the causal chain for delivering high quality health services. While separate health programs and governance programs can independently achieve results, these findings imply that integration amplifies sectoral outcomes. Although the study did not test governance interventions alone, prior research suggests it is unlikely a stand-alone governance program would have delivered similar results (Ciccone et al., 2014).

Stronger Health Governance Structures and Social Accountability

The findings regarding stronger HTCs in treatment communes demonstrate that strengthening local government capacity and supporting social accountability are particularly important elements of an integrated governance approach. We posit that these two elements could explain the added value of integrating governance and health programming.

An integrated approach to these interventions may overcome a critical bottleneck between citizens and local government. Social accountability efforts to improve service delivery often fail due to lack of response from higher level decisionmakers (Arkedis et al., 2021; Wetterberg et al., 2016). For example, a series of seminal studies have focused on the effects of community monitoring on service delivery in Uganda (Bailey & Mujune, 2021; Björkman & Svensson, 2009; Björkman Nyqvist et al., 2014). The most recent research, analyzing effects of years-long support to community advocates, shows that such efforts in Uganda led to notable changes in accountability relations. However, in only eight of 18 districts did officials fulfill or exceed stated commitments to improve health services (Bailey & Mujune, 2021).

Notably, HTCs in Senegal were significantly more likely not only to have identified health service delivery issues but also to report using municipal resources to improve services in the integrated governance treatment communes in our study. These results suggest that, by complementing social accountability at the facility level with capacity-building and resource mobilization for commune-level governance bodies, the integrated governance approach increased local government responsiveness to deliver concrete improvements in health services. Further research might explore whether and how these health facility readiness improvements were spurred by new or enhanced collaborative processes, perceived value by citizens or government in taking direct action to address identified problems, and/or clarified roles and enhanced capacity for health service planning, delivery, and monitoring that could signal a persistent shift in systemic, collaborative accountability efforts (Halloran, 2021).

Despite these encouraging results, it is important to emphasize that—like many others (Dunsch et al., 2017; Mant, 2001)—the study links integrated governance interventions with improvements in services and facility-level processes and readiness. More research is needed to make the link between governance interventions and actual patient outcomes, such as mortality and morbidity.

Implications for Health Services in Senegal

The findings suggest that achieving quality, universal health care is not only a health-sector issue but requires a more integrated approach. Specifically, the findings suggest that strengthening the capacity and involvement of municipal administration and health governance bodies adds value to more technocratic support to health facilities. In Senegal, national, regional, and local government agencies responsible for health service delivery could benefit from taking an integrated approach to improving health service delivery that attends to health facilities, health governance, and the wider governance system. Further research will deepen our understanding of the effects of integrated programming.

Implications for International Development Program Design

If integrated programming can add value, then program designers and funders need to pay attention to cofunding, colocation, and concurrent timelines. Support for collaborative work planning, activity design, implementation, and shared learning would support integrated programming. In congruent locations and time frames, sector-specific programs and governance strengthening program can bring their tools and expertise. When collaboration is intentional, well-resourced, and encouraged by stakeholders at multiple levels, enhanced multisector outcomes could be realized if intersectoral barriers, including siloed funding and pressures for sectoral indicator performance, could be addressed. Additional research in different contexts, including replicating a similar research design in other sectors, would further illuminate the patterns reported here.

For the global community to continue and accelerate progress to its collective SDGs, this research underscores the value of investments in integrated governance and encouraging coordinated programmatic investment. Simultaneously strengthening both direct service delivery and the wider governance system can achieve greater advancements in sustainable development than either alone.