Key Findings

Victims and witnesses (V/Ws) of severe community violence in the Piedmont Triad region of North Carolina do not receive adequate services to support their participation in the criminal legal system (CLS). In fact, 11 of the 20 recent V/Ws of severe community violence the research team spoke with reported that they were not offered any resources or services following their violent incidents. Interviewed CLS and community professionals largely agreed about the lack of resources and services within the CLS and community to support V/Ws adequately. A lack of services to V/Ws of severe forms of community violence results in unresolved trauma that likely has many negative impacts for V/Ws, including hindering CLS participation in these cases.

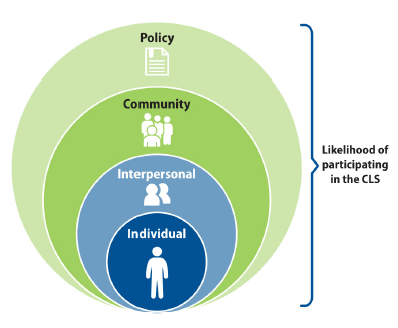

Findings follow the structure of the socioecological framework. The most frequently reported barrier to CLS participation from both V/Ws and professionals was the policy-level fear of retaliation for participating in the CLS. Professionals indicated a need for more safeguards and strategies to protect V/Ws, while V/Ws emphasized the danger that they face by participating. Thus, it appears that the CLS needs to do more to protect V/Ws in the Triad region to encourage V/W CLS participation and protect public safety.

Other commonly described barriers to V/W participation in these cases included the community-level barriers of distrust of the police and adherence to a community-wide attitude opposed to sharing information with the police. At the individual level, V/Ws mentioned a fear of self-incrimination based on real or perceived illegal involvement by V/Ws.

Motivators to CLS participation that were endorsed by both V/Ws and professionals include the individual-level belief that participation is the morally right thing to do, the interpersonal-level motivators of having a trusted CLS actor to report to, and certain crime or victim characteristics that motivate participation.

V/Ws and professionals reported many needs to promote greater V/W participation in the CLS. These include the policy-level needs of more comprehensive follow-up with V/Ws by the CLS; improved safety measures for V/Ws, including anonymity and protection/relocation assistance; and greater resources within the CLS to support V/Ws, including through victim advocates. Needs at the community-level include improving resident trust in the CLS. The research team highlights the need for sustained V/W engagement by the CLS, including through employed victim advocates and warm handoffs between agencies, as an immediate need to increase V/W participation in cases of severe community violence and to improve broader community trust in the CLS.

Introduction

Community violence includes assaults, shootings, homicides, robberies, and other violent acts that occur outside the home between unrelated individuals, who may or may not know each other (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024). Many incidents of community violence are severe, involving a firearm or other deadly weapon and resulting in physical injury or death. Yet, the criminal legal system (CLS) struggles to hold offenders accountable for these incidents. According to data collected by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) on its Crime Data Explorer website, in 2023, only 46 percent of aggravated assaults, 28 percent of robberies, and 57 percent of homicides were solved through an arrest or other means in the United States (Federal Bureau of Investigation, n.d.). Importantly, these figures do not account for acts of severe community violence that were not reported to the police. Notably, the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that only about one-half of serious violent crimes are reported to the police each year (Thompson & Tapp, 2022, Table 4).

Solving crimes of community violence often requires victims and witnesses (V/Ws) of these crimes to participate in the CLS, first by reporting the crimes to law enforcement, and then by providing information that can help identify suspects and build cases for prosecution. In fact, research shows that V/W participation significantly increases the likelihood of arrest and conviction in cases of severe community violence (Baskin & Sommers, 2010, 2012; Cook et al., 2019; Scott & Wellford, 2021). There are no comprehensive national statistics on V/W participation in police investigations or courtroom proceedings, but evidence suggests that V/W participation rates in these CLS stages are likely even lower than at the crime reporting stage (Lowery & Bennett, 2018; Palmer et al., 2020; White et al., 2021). CLS actors acknowledge that V/Ws of severe community violence are reluctant to participate across all phases of the CLS (Brookman et al., 2019).

There are many reasons why V/Ws of severe community violence choose not to participate in the CLS. For instance, research shows that V/Ws residing in high-crime areas often lack trust in the police because of direct or vicarious experiences with both police mistreatment and harassment (i.e., over-policing) and neglect (i.e., under-policing), which discourages their participation in the CLS (Brunson & Wade, 2019; Nguyen & Roman, 2024). Additionally, some V/Ws fear physical or social retaliation for participating in the CLS (Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003; Leovy, 2015). In some areas, V/Ws adhere to an anti-snitch culture which poses a barrier to participation, especially in cases involving gang-related violence (Leovy, 2015; Whitman & Davis, 2007). For V/Ws who do participate in the CLS, many experience poor treatment from police and prosecutors, insufficient support services, and a system that generally requires reliving of traumatic events to pursue justice (Bowles et al., 2009; Ellison & Munro, 2017; Slovinsky, 2023).

Most of what is known about V/W decision-making following severe community violence comes from studies focused on why V/Ws do not engage with the CLS. Many studies concentrate on the reporting stage, with common reasons for not reporting the crime to the police being a lack of trust and perceived illegitimacy of the police, adherence to an anti-snitching ethos, and fear of retaliation from perpetrators. Although these studies provide critical insights into the obstacles that prevent engagement, few examine experiences of V/Ws who do choose to participate in the CLS, particularly during the investigation and court proceeding phases. As a result, far less is known about what motivates V/Ws to participate and the challenges of V/W participation beyond the initial act of reporting the crime or providing information to the police. To build a more complete understanding of the barriers and motivators to V/W CLS participation across different stages of the system, there is a need to study V/Ws who choose to engage beyond the reporting stage. Furthermore, there is a need to incorporate perspectives from both V/Ws and professionals who work regularly with V/Ws, such as law enforcement officers, prosecutors, and victim service providers. Each group may provide unique points as well as overlapping sentiments. Therefore, including both perspectives allows for a more complete picture of the barriers, motivators, and needs related to V/W participation in the CLS in cases of severe community violence.

Study Objectives

This study team explored the barriers, motivators, and needs of V/Ws1 of severe community violence that affect their decision-making about whether to participate in the CLS or not. For the purposes of this study, the research team defined severe community violence as serious forms of violence like homicide, aggravated assault, and robbery that typically occur outside the home and often involve strangers or acquaintances. This type of violence, which has also been called “street violence,” excludes sexual violence and domestic violence. This definition aligns with previous research on the topic (Gorman-Smith et al., 2001; Roman, 2024). For this study, participation in the CLS refers to a V/W’s engagement with the CLS along a continuum, which includes initial reporting to the police about an incident, providing a statement to law enforcement and engaging in follow-up investigative activities, and engaging in court proceedings like speaking with prosecutors and testifying in court. This study includes perspectives from recent V/Ws of severe community violence and professionals who work with them. By including both perspectives, we explored their interactions and provides insights about the relative importance of various barriers, motivators, and needs according to each group. The objective is to develop practical solutions that enhance V/W engagement at all levels of the CLS while addressing the needs and challenges of V/Ws throughout the process. The area of focus for this study was the Piedmont Triad region of North Carolina (NC).

Methods

The research team used the COREQ (COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research) Checklist (Tong et al., 2007) to guide reporting in the Methods and Results sections. Therefore, personal characteristics (e.g., gender, experience, training) of research team members (e.g., recruiter), V/Ws, and CLS professionals are provided in these sections.

Study Participants

Focus Groups with Professionals

The research team conducted three in-person focus groups with 23 professionals who work regularly with V/Ws of severe community violence in Greensboro, High Point, Winston-Salem, and Randolph County, NC, referred to as the Triad region of NC. We conducted three individual virtual interviews with professionals who could not attend a focus group session for a total sample of 26 professionals. Professionals included state and federal prosecutors (13 percent), victim/witness advocates embedded within the CLS (22 percent), law enforcement investigators (43 percent), and community-based V/W service providers (22 percent). Participants were recruited via contacts at law enforcement agencies, prosecutor’s offices, and community-based organizations via outreach from the research team and a community member who worked alongside the research team for recruitment purposes. The research team and community member had established relationships with local agencies through prior work. Contacts were able to identify specific personnel within their agencies who work directly with V/Ws of severe community violence. Those personnel were then contacted by the research team for recruitment into the study. Additionally, these agency contacts were able to suggest contacts at other agencies to recruit for study participation.

Individual Interviews with V/Ws

The research team conducted in-person interviews with 20 V/Ws who had directly experienced or witnessed severe community violence within the last 5 years. They used two recruitment methods recommended for research involving similar populations (Eidson et al., 2017). First, a community member served as a trusted liaison between the research team and potential participants. This person was able to facilitate recruitment because of his extensive professional experience having provided counseling, mentorship, and resources through a community-based organization to individuals who have experienced community violence and because of his established leadership role as a faith leader within the community. He recruited from the pool of individuals he had worked with. This person also reached out to other local organizations working with individuals who may have experienced severe community violence, such as area shelters for unhoused individuals. Those organizations allowed the research team to come into their spaces to explain the study and pass out recruitment materials. Second, we used a snowball sampling approach. Completed study participants were asked to tell others in their networks about the study and, if they were interested, provide prospective participants with contact information for the research team. This method proved successful because it leveraged the trust and rapport the researchers had built with participants, providing access to potential participants who might have not known about the study or otherwise could have been reluctant to engage with the research team. It was common for prospective research participants to be recruited by participants who had completed the study, especially when those participants shared living space.

The research team developed a pocket-sized informational card with contact information including an email address, phone number, and QR card, which they gave to potential participants after briefly describing the study. Individuals who were interested in study used the contact information to access a screener for participation, either by speaking with the research team directly or through an online form. To qualify for the study, an individual must have experienced at least one incident of severe community violence within the last 5 years. We asked individuals what type(s) of incident they experienced to screen out those who had experienced violence that would not be considered severe community violence, such as domestic, intimate partner, or sexual violence. Once we determined a participant to be eligible for the study, we scheduled an interview time. If a participant needed transportation to the interview location, the research team provided it.

Table 1 provides demographic information for this study’s sample of V/Ws. One can see that the sample overrepresents older adults. Although there is no known population of V/Ws in the Triad region to compare the sample’s demographics against, national surveys show that most victims of severe community violence are young adults (Thompson & Tapp, 2022, Table 3). The research team faced challenges recruiting young adult V/Ws. According to information shared with the community member recruiter, this appeared to result from a lack of trust about the research study among this population. Readers should consider that this study’s results largely represent the perspectives of older V/Ws of severe community violence.

Design & Procedure

Focus Groups with Professionals

The research team developed a focus group discussion guide to ask the professionals about barriers, motivators, and needs affecting V/W participation in the CLS and the services their agencies provide to V/Ws. The research team developed this set of questions, which is included in Supplement A, based on their experience and input from three professionals working in CLS and community crime prevention organizations (supplements to the text can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17485726). Focus groups took place in a private room accessible only to the researchers and participants during the session. A note taker was present in each focus group along with an interview facilitator. The facilitator was a senior research team member who has conducted numerous focus groups and was knowledgeable about the literature on V/W participation and about the CLS in general.

The research team analyzed written notes using a thematic analysis framework like the six-step process of Braun and Clarke (2006). This includes (1) becoming familiar with the data, (2) generating initial codes to summarize data segments, (3) searching for and identifying themes that group codes into broader patterns, (4) reviewing themes for coherences and may include merging, splitting, or discarding themes, (5) defining and naming themes as they relate to the research questions, and (6) writing the report to interpret the data meaningfully (Ahmed et al., 2025). This framework is suitable for both inductive and deductive approaches to data analysis (Majumdar, 2022). After becoming familiar with the data, a senior member of the research team, who was also the focus group facilitator, conducted the initial coding. They entered each data point in the initial coding into an Excel database, including the type(s) of professional who expressed it and a quote, if applicable, or other contextual information related to the data point. Following the initial coding, the senior research team member reviewed and organized codes in the database into themes based on existing literature about barriers, motivators, and needs related to V/W participation in the CLS. The senior research team members further split themes into sub-themes to add nuance, as needed. A second research team member, experienced in qualitative analysis and knowledgeable of the literature on V/W participation having assisted with a systematic literature review on the topic, reviewed the database to validate the placement of coded datapoints into themes and sub-themes. The two research team members met to discuss interpretations and reach consensus on the final set of themes and sub-themes for barriers, needs, and motivators.

Interviews with V/Ws

The research team developed an interview guide for participants to reflect on recent incidents of severe community violence they experienced within the past 5 years, including their experiences with the CLS following the incident and V/W services they were told about or received. As shown in the interview guide in Supplement B, the research team designed the set of questions to learn about barriers and motivators to CLS participation at each stage of the CLS and what the participant would like to see improve in the CLS’s response to V/Ws of severe community violence. The research team developed the interview guide following a systematic literature review of the factors that impact V/W CLS participation in cases of severe community violence and in discussion with each other and community- and CLS-based partners. Interviews were semi-structured, allowing the interviewer flexibility in accessing responses from participants. For example, the interviewer worked with participants to identify a primary incident to discuss based on how recently the event occurred (more recent events were prioritized) and how close the V/W was to the event (e.g., direct eyewitness was prioritized over being nearby when the incident occurred).

Once the interviewer and participant agreed on a focal crime incident to discuss, the interviewer asked, “Can you tell us a little bit more about what happened in the [FOCAL EVENT] you mentioned [WITNESSING OR EXPERIENCING]?” Participants often provided a lengthy narrative response to this question. For example, many participants included how the participant was involved (e.g., as a victim, third-party witness), where the incident took place, who was involved, and whether law enforcement knew about the incident. The initial description set the stage for how subsequent questions were asked. The interviewer took care to reflect participants’ language back to them, such as one participant’s use of the phrase “unalive me” to indicate that an assailant attempted to kill her. The interviewer took opportunities to verify information participants provided in the initial description of the incident instead of asking each question in the interview guide verbatim. For example, if during the description, a participant stated that someone was injured, the interviewer would summarize and state back to the participant something like, “You mentioned you were hurt during the incident. Did you seek medical treatment or go to the hospital for those injuries?” Or, if a participant mentioned that the police showed up in response to the incident, the interviewer would reflect back to the participant something like, “You mentioned that police arrived on the scene. Do you know how the police knew about the incident? For example, did you call 911 or do you know if someone else did?” This provided a starting point to ask participants about their decisions to report or not report an incident to police. If a participant did not mention a police response in their description of the incident, then the interviewer asked whether they knew if the police were aware of the incident, and, if so, how. If a participant stated that they did not report the crime to the police, the interviewer first asked why they did not report it to the police in an open-ended format. Then, the interviewer showed participants a list of common reasons why V/Ws do not participate in the CLS, which were informed by a systematic literature review on the topic. The team included these reasons on a showcard that interviewers showed participants during the interview to ask them whether any of those reasons applied to their experience. Similarly, if a participant stated that they did report to police, they were asked why they did report.

The interview questions proceeded according to the direction provided by the participant, but we obtained consistent information from participants about each incident described. If time allowed, participants were able to discuss more than one eligible incident.

Each interview took place at a community-based organization behind a closed door with only the interviewer and participant present. Participants received transportation to the interview site by the trusted community partner who assisted with recruitment, if needed. The team offered participants refreshments upon arrival. The interviewer was the same female senior team member who facilitated the professional focus groups. Participants provided informed consent prior to participation in the interview. The interviewer told participants that they did not have to answer any questions that they did not feel comfortable answering, that questions could be skipped, and that the interview could be discontinued at any time. No participant discontinued the interview. The interviewer also told participants not to mention any identifying information during the interview about other parties involved in the incidents or locations of incidents.2 The interviewer acknowledged that the subject matter may be difficult to talk about and that the interview could be paused for breaks at any time. The research team obtained a certificate of confidentiality for this study from the National Institutes of Health given the sensitive nature of the subject matter being discussed. Participants were told how the certificate of confidentiality protects their data during the informed consent process. The interviewer also asked participants if they would consent to having the interview audio-recorded. Those who did not wish to be audio-recorded were offered the option to participate with the interviewer taking notes during the interview. Three participants declined to be audio-recorded. Each interview lasted approximately 45–90 minutes. Participants were compensated with $50 cash at the conclusion of the interview.

We audio-recorded interviews using Audacity software and then transcribed the recordings using a professional transcribing company. For those who did not wish to be audio-recorded, the interviewer took detailed notes during the interview. When possible, the interviewer included direct quotes from the participant in the notes. These interview notes were included along with recording transcriptions in the analysis.

The research team analyzed transcriptions using a similar approach as described for the focus groups. Two researchers were responsible for coding 10 V/W interview transcriptions. One of the coders was a senior member of the research team who also conducted the V/W interviews and analyzed the professional focus group data. The second coder also helped analyze the professional focus group data. The senior team member did an independent coding of two initial transcripts and entered the data into the same database alongside the coding and themes from the professional focus groups. This included each V/W data point along with the participant number that expressed the theme and a quote, if applicable, or other contextual information. The goal of combining the V/W findings with the professional findings was to see where there was overlap in themes in the barriers, motivators, and needs, and where there was divergence. After the senior team member coded the initial two interviews, the two researchers met to discuss the procedure and review the initial coding to reach agreement on interpretations. The second coder then coded two transcripts and the coders met again to discuss interpretations and reach convergence. The procedure was followed until all 20 interview transcripts were coded. The senior team member reviewed the final database, which contained coded data points from all 20 V/W interviews and the three professional focus groups and arrived at the final themes and sub-themes.

For the V/W interview data, the senior team member who conducted the V/W interviews reviewed the transcripts to extract specific data points for a quantitative summary of incident characteristics (see Table 2 for characteristics extracted). They created a separate database to store data about each incident.

Table 2.

324394Characteristics of 36 community violence incidents described by 20 V/Ws

Results

The 20 V/W participants discussed 36 unique incidents of severe community violence. The types of violence described included fatal shootings (19 percent), shootings with injury (8 percent), shootings where no one was struck (17 percent), non-shooting assaults (37 percent), and robberies (20 percent). See Table 2 for the types of incidents that participants experienced and whether they were a victim or witness in each.

According to the V/Ws, law enforcement became aware of 24 (67 percent) of the 36 incidents. Participants did not believe law enforcement knew about eight incidents (22 percent), and participants were not sure whether law enforcement knew about four incidents (11 percent). V/Ws reported participating in the CLS to some degree in 21 of the incidents (88 percent of incidents known to law enforcement), most often by providing an initial statement to police upon an officer’s response to the scene or hospital. In three incidents known to law enforcement, V/Ws did not participate because they did not want to be involved.

Table 3 describes what V/W CLS participation looked like among the 21 incidents involving participation. Importantly, the counts are not mutually exclusive because a V/W could have participated at multiple stages of the CLS. In 18 incidents (86 percent of incidents involving CLS participation), V/Ws provided an honest initial statement to law enforcement or made a 911 call to the police indicating their willingness to participate in the CLS. Importantly, in nine of these incidents, the V/W reported not hearing from law enforcement again after providing their statement. Only two incidents involved a V/W participating in a follow-up interview with law enforcement, and three incidents involved a V/W participating in court proceedings. Thus, although this study’s findings explore decision-making about CLS participation across the system, V/Ws’ real-world experiences with CLS participation primarily involved speaking to law enforcement during their initial response, at least among the incidents discussed as part of this study.

Table 3.

324395V/W participation in CLS for incidents described during interviews

Next, we present findings on common barriers, motivators, and needs related to CLS participation, as reported by their sample of professionals and recent V/Ws. We organize these findings according to the socioecological framework (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which is a popular organizational framework that posits that behavior is influenced by the systems in which an individual is embedded. In this case, the decision to participate with the CLS is influenced by the context in which a V/W experienced the violent incident. The context includes interconnected layers of influence at the most proximal to the most distal levels. At the most proximal level of influence are individual V/W characteristics that impact CLS participation decisions. The next level of influence is the interpersonal level, which includes dynamics between the V/W and others involved in the incident, including the perpetrator, other witnesses, and individual CLS actors. At the next level are community influences, which may include neighborhood, peer, and family norms, expectations, and experiences. Finally, at the most distal level of influence are policy-level influences, including policies and laws set by CLS actors, legislatures, and the larger CLS that dictate CLS actors’ rules of engagement with V/Ws and ensure due process in criminal proceedings (see Figure 1). Importantly, it is not always easy to categorize a finding neatly within one level because the levels of influence often interact. However, the authors have identified a main level for each finding to help with the organization and interpretation of the findings. The authors report the most common themes and sub-themes identified in the barriers, motivators, and needs findings. The research team identified the most common themes and sub-themes based on a count of mentions across participants.

Barriers to Participation

Policy-Level Barriers

The most mentioned barrier to CLS participation from both V/Ws and professionals was fear of retaliation (see Table 4). (Note: theme and sub-theme labels are presented in italics throughout this report.) Fear of retaliation could be perceived as an individual-level fear but is influenced by more distal variables, such as those identified as sub-themes as participants described their fear of retaliation. Sub-themes at the policy level included a lack of protections for V/Ws, which was mentioned by both professionals and V/Ws. One V/W described how a perceived lack of protection led to their decision not to report an incident to police: “I didn’t want any more problems because when you report stuff to the police, they might investigate it, and they might even arrest the person. But they’re not going to be there for your protection if anything else occurs or whatever.” When prompted further, the participant continued: “He [the perpetrator] might have tried to retaliate in some sort of a way… But I don’t think the police have enough concern where they’re going to make sure nothing else happens or whatever or they can’t afford to watch you twenty-four hours a day.”

Professionals indicated a need for more policy-level safeguards and strategies to protect witnesses, whereas V/Ws emphasized the danger that V/Ws face—often life or death circumstances—and therefore, the CLS needs to do more to protect V/Ws. Two V/Ws stated that they do not think that the CLS takes witness intimidation seriously. Others mentioned that there is no accountability or deterrence for acts of witness intimidation.

A policy-level barrier mentioned only by V/Ws was the sub-theme of paperwork and discovery, which led to fear of retaliation. This sub-theme included explicit discussion from V/Ws about the fear of being documented on paperwork by law enforcement, an action guided by CLS policy, and this information becoming known to a perpetrator through the discovery process, which can place V/Ws at risk for retaliation. One V/W stated, “That’s my life in jeopardy right there. If I was to speak to them [police], I’m going to go on that person’s paperwork. On the motion in discovery. Unless that jeopardizes me. You know, I’m going to get hurt. Because automatically like, they’re on the phone, they’re in jail, and they’re like, ‘All right, guess who’s on my paperwork?’”

Another policy-level barrier mentioned by both V/Ws and professionals was a lack of accountability for offenders through the CLS. Participants spoke about the effects of lack of accountability, which include cases going cold, offender punishment not being worth V/W effort to go through the CLS, and a snowball effect wherein offenders persist with violence because they have learned they can get away with it. One V/W stated, “And then, the violence increases when the witness tells the police officer what they seen or who they seen, you know? And it gets them in trouble, I mean, because sometimes, they’re not took off the street immediately. You know, they have to be tried and convicted, and sometimes, that’s results in more violence.” The V/W went on to explain that that even if a case goes to trial, it does not guarantee a conviction, and this prevents V/Ws from coming forward with information in violent incidents.

Another barrier mentioned by both groups was that going through the CLS is a burdensome process for V/Ws because of transportation issues, missing work, or needing childcare. Although these are individual-level experiences, these burdens are often exacerbated by factors at the more distal system levels, with the CLS system not equipped with resources or assistance to help V/Ws navigate these needs.

Finally, one barrier mentioned only by professionals was the siloed nature of the CLS. Under this theme, professionals described that agencies typically do not work well together to facilitate or sustain V/W engagement with the CLS. Many of the V/W participants in this study did not have much experience with the CLS beyond providing an initial statement about the incidents they experienced. Therefore, V/Ws did not have much detail about inner workings of the CLS and how agencies work together (or do not) for the incidents they described.

Community-Level Barriers

Concentration of violence was a sub-theme at the community level under fear of retaliation. Participants stated that community violence often occurs in concentrated areas where V/Ws and perpetrators live together and know one another. One V/W described the complex community-level dynamic of the apartment complex where he lived, which was a very concentrated environment where interactions between residents could take on elements of a domestic relationship given that people live in close quarters, they know one another, and they are able to use those relationships to bully or hold power over one another:

They [offenders in the incident described] knew where I lived. I knew that hangout spot. It is kind of domestic, too. You know how domestic violence it’s in the household? It was kind of domestic, too, because we all know each other. It’s like a miniature community within those apartments in a couple of blocks. It is kind of domestic because they’re only going to bully people that they know in that neighborhood, that they know they can bully because they know people in that neighborhood.

The concentration of violence exacerbates fear of retaliation according to participants because individuals on scene in violent incidents often know one another and know who was present to witness or experience it and subsequently provide information to the CLS.

Another community-level barrier is related to community norms of “no snitching” and a belief in street justice or wanting to handle a situation oneself instead of relying on law enforcement. In discussing the barrier of adherence to the “no snitching” norm, V/Ws described the collective mentality around this norm, meaning that V/Ws perceive that their community adheres to the norm and that the norm is taught and reinforced through the community. One V/W said of snitching, “It just ain’t cool, bro. Snitching not cool, bro. Snitching ain’t never been cool whether it’s cops or not. You know what I’m saying? You snitching to a teacher on another classmate, that still ain’t cool. You feel me? It’s the code. It’s the ethics of snitching. Don’t nobody want to do that.” V/Ws also described the repercussions of violating the norm, which included violence, social isolation, and threats. One V/W stated, “If you talk, you know what’s going to happen to you. I mean, if you snitch, you’re labeled a snitch, either way, some kind of way. You know, it’s sad because you can’t live your life normal, you know? It’s like, you don’t have any freedom of speech. If you even wanted to talk, it’s like, you don’t talk, you know? And that’s not a good feeling, you know? That’s not a good feeling at all.” Another V/W comingled feelings about the “no snitching” norm and street justice stating, “I don’t want to be a snitch. I don’t want to be a buzz kill. I only want to do things in a man way. If we’re having problems or whatever, I want to be able to go over there and get it from you and leave it at that. No cops or anything.”

Interpersonal-Level Barriers

Professionals and V/Ws both discussed the barrier of a negative history with law enforcement and specifically that Black, Hispanic, and immigrant V/Ws are more likely than White and US-born V/Ws to experience this barrier. Negative history with law enforcement could be perceived as an individual-level barrier, yet this negative history is often influenced by interactions at the interpersonal level, such as poor interactions with specific CLS actors or agencies.

Backfiring and victim blaming were common sub-themes mentioned only by V/Ws about their negative interactions with law enforcement. Backfiring refers to situations in which the person who is reporting a crime ends up being arrested. These experiences were both direct for the V/W participants or vicarious, meaning that V/W participants have seen this happen to others in their community. One V/W stated, “We don’t call the police because the police, they turn the situation around on you, and everybody go to jail.” Victim blaming is similar in that V/Ws had experienced situations where victims have been blamed by law enforcement for putting themselves into the position to be victimized. Again, this experience could have been either direct or vicarious but prevented V/Ws from wanting to engage with law enforcement in future incidents. Other sub-themes under negative interactions with law enforcement were police apathy and police bias. Police apathy included perceptions by V/Ws that police do not care about the incidents that the V/W experienced or that are occurring in the community more broadly and police bias included perceptions that police enter situations with their own biases that lead them to act unfairly toward V/Ws of community violence. These perceptions affect V/W trust in law enforcement and pose barriers to participation in the CLS. One V/W stated, “That’s why a lot of people don’t like to get involved with the police because they don’t feel like they really have a concern for them to actively pursue cases and find out what’s going on.”

Individual-Level Barriers

An individual-level barrier mentioned by both V/Ws and professionals was V/W’s own involvement in criminal activity at the time of the incident, which prevents V/W participation because of fear of self-incrimination.

Other barriers mentioned only by V/Ws were questioning of self-defense, with three V/Ws discussing concern about whether use of self-defense during the incident would lead to them being charged with a crime.

Finally, some V/Ws said that they did not report the incident because they felt that they did not have enough information about the perpetrators or the incident to report it to the police. This was typically due to the V/W not knowing the identity of the perpetrator or having a good description of them to share with the police.

Table 4.

324397Barriers to V/W participation by participant group

Motivators of Participation

Policy-Level Motivators

Only professionals, and no V/Ws, discussed resources and support for V/Ws as motivators to participation. They discussed resources like victim compensation, transportation, and relocation assistance. It is important to note that V/Ws do not know what they do not know when it comes to resources and support available. Six of the 20 V/Ws said they are not aware of resources available to V/Ws; 11 V/Ws were not offered any resources or supports following their violent incidents. The authors discuss this important finding in the Discussion section.

Interpersonal-Level Motivators

The most mentioned motivator for CLS participation by both V/Ws and professionals was that certain types of victims or crime types lead to greater V/W participation (see Table 5). V/Ws said that when “pillars of the community,” relatives, or “a loved one” was the victim, it was likely to increase their willingness to participate in the CLS. One professional spoke specifically about families of victims wanting justice, so they are more motivated to work with the CLS. Crimes that involved children or elderly victims or those that involved a serious injury or death were described as leading to greater participation. One V/W deemed murder child molestation, and rape as exceptions to the street code of not talking to the police.

Table 5.

324398Motivators to V/W participation by participant group

Both professionals and V/Ws discussed the importance of having a trusted CLS actor as a motivator. Trust can be built based on how a CLS actor interacts with a V/W in a specific incident or because of a history or relationship that a CLS actor has developed with a V/W over time. Building trust in specific incidents includes having a point of contact who maintains consistent communication with V/Ws throughout the CLS process, which demonstrates to a V/W that the specific actor is trustworthy even if the V/W distrusts the system more generally. One V/W described what their interactions looked like with trusted law enforcement actors: “When an officer stops me, and I know him, I know a lot of officers, I’m not going to run from them, and I’m going to talk to them… I’m like, ‘Hey, how you doing?’ And I laugh and giggle and cut up because I can talk shit to them.”

Individual-Level Motivators

V/Ws and professionals mentioned that sometimes V/Ws are motivated to participate because it is morally the right thing to do. One V/W who witnessed a homicide stated that he stayed to speak with police even though most people ran away. He said,

Once the police arrived on the scene, I wasn’t one of those that left and then stood back and say I don’t know what happened, that I wasn’t here, because it would have just ate at my conscious. It would have ate at my conscious bad if I would have pretended that I didn’t see anything and that hey, I don’t know nothing… I’m like well, right is right and wrong is wrong. And I don’t care who you are and what color you are. He shot that kid over money, over something that was senseless. He took that man’s life. And even though we all grew up together and the street has a code and rules and blah blah, right is right and wrong is wrong. That boy died a senseless death, and for me not to say anything about it would have bothered me for the rest of my life because he was wrong.

A motivator mentioned by V/Ws only was removing an immediate threat. One V/W described calling the police following the shooting of a neighbor: “At that point, I had no problem calling 911, because the desire was to have police come and show up and get this guy, arrest him, remove the threat basically.”

Needs to Better Support or Increase Participation

V/Ws and professionals mentioned multiple needs that must be met to increase and improve V/W participation in the CLS (see Table 6).

Table 6.

324399Needs to promote greater V/W participation by participant group

Policy-Level Needs

V/Ws and professionals discussed the need for better or more comprehensive follow-up with V/Ws. Many V/Ws never received any follow-up or updates from the CLS after the initial statement to law enforcement, and it should be re-emphasized that many were unaware of resources available to V/Ws and were not offered any formal resource supports. This need could potentially be addressed by policies to mandate consistent follow-up with V/Ws. Many V/Ws described needing follow-up so that they could learn the outcome of incidents they were involved with, whereas professionals described the importance of follow-up with V/Ws to keep them engaged with the CLS process.

V/Ws and professionals described the need for anonymity during V/W participation in the CLS process. Specifically, V/Ws wanted opportunities to speak with police off the record or to provide information in a way that did not endanger or identify witnesses. V/Ws often questioned current processes and policies that the CLS uses and why investigations are conducted in ways that identify V/Ws when there are dangers to V/Ws with little to no protection provided by the CLS. For instance, one V/W stated, “And free from—because people put statements out there. Then that’s paperwork. You don’t want to be on no paperwork. That gets you killed. Because people don’t even realize that. You’re thinking you’re doing the right thing for being on some paperwork, but who’s going to be there to save you when it’s that? They ain’t going to be there, I tell you. They ain’t going to give a damn, and you’re just going to be in there as a dead person.” Later this participant said, “Victims and witnesses should always be anonymous.” Another V/W said that V/Ws should know that their name will be documented and that a defendant may get that information. This should be communicated transparently before V/Ws decide to participate, otherwise it feels like a betrayal to the V/W and may impact community trust in the CLS and future V/W participation. The V/W has taken it upon herself to educate others about this possibility because she felt law enforcement would not. One V/W stated that she would have liked a virtual option to join the courtroom and talk to the jury on camera rather than in person. Another V/W stated that photographs should not be taken in the courtroom.

The need for witness protection and relocation assistance was the most mentioned need expressed by V/Ws, which was also mentioned by professionals across all three focus groups. V/Ws noted challenges associated with relocation, which include leaving family and everything one is accustomed to. Another V/W stated that even if someone relocates, a motivated suspect or defendant could still find them. Another V/W said many V/Ws who are relocated will want to come back to the community eventually because it is too difficult to stay away, which will put them in danger.

Professionals discussed what they need within their own organizations or communities to better support V/Ws. Many professionals described a need for resources that currently they feel they do not have enough access to because of organizational factors like staffing capacity or funding available for resources such as relocation assistance. Professionals also mentioned the importance of removing any conditions placed on resources available to V/Ws. For example, willingness to provide resources should not be contingent upon a V/W’s willingness to participate in the CLS. Professionals described the need for improved collaboration within the CLS. This would look like a continuum of support for V/Ws as they navigate through the CLS and continuous touch points with V/Ws to make sure they are still engaged. Many professionals talked about the need for multidisciplinary, coordinated teams and one-stop-shop approaches. Some stated that services for V/Ws are available, but there needs to be better collaboration/coordination among existing service providers. Professionals also described the need for better or warm handoffs between partners working with V/Ws. This prevents V/Ws from having to tell their story over again and relive the trauma, and one trusted resource provider can vouch for the new provider.

Professionals also expressed a need for law enforcement training on how to talk to victims. This relates to what V/Ws said about the need for more compassion from law enforcement when responding. One violent crime investigator said, “As you come in as a detective, you don’t go to class to learn to talk to victims and witnesses. You just learn from patrol, and it takes time to learn that.” He went on to mention the value of a social skills class for new officers. Professionals shared strategies or tactics that they have learned through experience about how to build rapport with V/Ws through finding common ground. As one detective shared, he was working with a victim who was shot, but the victim did not want to talk to the police. The detective noticed the victim’s accent and pointed out their similarity in that he and the victim both had an accent from the same place. Then, after a few minutes of talking, the victim broke down and told the detective who shot him and other details of the incident.

Finally, many professionals discussed the need for victim advocates to engage with V/Ws, preferably immediately following an incident. One law enforcement officer described what they saw as a benefit of advocates to law enforcement saying, “We need advocates because it is a fine line. You can get really attached to a case and victim to a point where it clouds your judgment. You wouldn’t be able to do your job and move on. That is why it is important to separate the victim side of things from the job of enforcing the law.” Prosecutors and victim advocates stated that the value that advocates brings is that they can “do the legwork” for V/Ws such as arranging transportation and reaching out to service providers until they can find one who is appropriate and available. Victim advocates can also provide those continuous touchpoints with V/Ws and provide direct support such as accompaniment to investigative interviews and court proceedings, which likely improves V/W engagement and participation.

Community-Level Needs

A common need stated by V/Ws only is the need for trust between the community and the CLS to increase the likelihood of V/W participation. V/Ws described building trust through activities like athletic leagues for youth led by law enforcement, officers taking youth to events, officers showing up in plain clothes to interact with the community, and officers taking time to play with children while out on patrol.

Interpersonal-Level Needs

Both professionals and V/Ws expressed a need for alignment between services offered and the needs of V/Ws. That includes alignment of the specific professional working with V/Ws to be sure that persons in those positions are the right people to earn trust with V/Ws and that the services provided match what the V/W needs.

Only V/Ws and no professionals stated a need for more compassion from responding officers. When asked what that could look like, V/Ws said that officers should show up with genuine concern, be attentive, and take time with V/Ws instead of “brushing them off”. For instance, a V/W summarized what they needed with the following, “I think that police can be a little bit more compassionate in situations, and offer resources, and follow-up with the victims to see how they’re doing or how they could be assisted, you know, because that type of thing [a violent experience], that’s something I’ll never forget. I will never forget, and it impacts on your daily life, and the things that you do, how you do things. So, I think the police can be a little bit more resourceful in situations like that. That would be helpful.”

Discussion

This NC Piedmont Triad region sample of 20 recent V/Ws of severe community violence and 26 CLS and community professionals who work with V/Ws of these crimes reported many common barriers and motivators to V/W participation in the CLS. Importantly, despite data collection occurring in one region of NC, many of these themes have been consistently reported in prior research based on a range of locations and sample characteristics (Brunson & Wade, 2019; Kubrin & Weitzer, 2003; Nguyen & Roman, 2024; Whitman & Davis, 2007). Fear of retaliation was the most frequently mentioned barrier in this study, with both V/Ws and professionals acknowledging that there are little to no protections available to V/Ws who participate in the CLS following an act of severe community violence and that V/Ws face real threats for participating. These findings suggest that CLS policy changes are needed to address V/Ws’ needs for anonymity and protection.

V/Ws in this study were keenly aware of the consequences of having their identities revealed in the paperwork shared with defendants during the discovery process, with many V/Ws questioning why the CLS cannot take additional steps to protect their identities. For instance, V/Ws stated that CLS professionals should be honest with V/Ws about the potential of their names being shared through discovery so that V/Ws can make informed decisions about their participation to keep themselves safe. Another recommendation is that law enforcement emphasize to V/Ws what the CLS is prepared to do to protect anonymity and V/W safety and the limitations of those protections. V/Ws also provided suggestions for ways that the CLS can better protect V/W identities and safety through measures like relocation assistance and strongly urged CLS professionals to consider ways that V/Ws can provide information in an anonymous manner.

To address system deficiencies regarding witness protection, jurisdictions may want to assess what resources currently exist, including identifying relevant system and community partners, capacity for simple safety planning, available discretionary funding for short-term relocation or provision of security systems or cameras for those who wish to remain in place, and existing and potential witness protection legislation. Examples of legislation that can assist in witness protection include statutes such as a California law (Cal. Penal Code § 1335) that allows witnesses to be examined before trial when there is evidence that a victim or witness is being “dissuaded” from testifying to preserve their testimony if they become unavailable for trial. Additionally, Colorado law (Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 24-33.5-106) created a witness protection board that provides funding available to prosecutors for witness protection efforts and witness protection training and resources for prosecutors and law enforcement. State-level legislation appears to be a promising avenue for increasing V/W protections and, as a result, increasing V/W legal system participation in violent crime cases.

At the community level, a poor relationship between residents of high-crime areas and the CLS, especially negative attitudes toward the police, was another factor that both V/Ws and professionals attributed to a lack of V/W participation in cases of severe community violence. V/Ws of these crimes often do not trust the police based on reported direct and vicarious experiences with both mistreatment and harassment (i.e., over-policing) and neglect (i.e., under-policing). A related barrier to V/W participation mentioned by both V/Ws and CLS professionals was the perception of V/Ws that the CLS is incapable of holding offenders accountable. Therefore, it seems that CLS efforts to improve resident trust in the system, especially the police, through programs aimed at improving police officer behavior like increased oversight and training, building community trust particularly in high-crime areas, and partnering with community groups to educate residents about the CLS’s limitations and capabilities are likely to promote CLS participation by V/Ws in cases of severe community violence.

Interestingly, when it came to discussing what the V/Ws and professionals thought was needed to increase or improve V/W participation in the CLS, V/Ws but not professionals mentioned a need to improve trust between the CLS and the community. It seems that although professionals recognize the lack of trust as a barrier to CLS participation, they focused on factors like improving resources, staffing, training, and coordination over external efforts to improve community trust when asked about their needs.

Since a common concern of V/Ws was feeling “brushed off” by law enforcement because of a lack of sustained communication, law enforcement agencies can likely improve participation by focusing greater effort on V/W engagement and communication and creating policies to do so. One way of accomplishing this is by employing dedicated victim advocates, which is discussed below. In addition to increasing V/W participation in a case, this investment in victim services is likely to improve broader community trust in the police and CLS. V/Ws who receive consistent and sustained engagement about their case are likely to communicate that to their social network, which should improve resident attitudes toward the police. If a law enforcement agency does not have a victim advocate in place, lead detectives should reach out regularly (e.g., every 4–6 weeks) to victims, family members, and key witnesses to provide case updates, even if there is no new information to share. Keeping V/Ws updated through consistent engagement appears essential for earning their trust and in turn the trust of their communities.

V/Ws and professionals provided fewer motivators to CLS participation than barriers but did note a few that seem to be within the control of the CLS. One interpersonal-level motivator mentioned by both groups is the importance of V/Ws having a trusted CLS actor that they can share information with. Other research has demonstrated that V/Ws can feel comfortable sharing information with a trusted officer or detective that they likely would not have shared otherwise (Bell, 2016; Leovy, 2015). When this relationship has been established, these V/Ws will even encourage community members to speak with that officer or detective in other cases by vouching for their character (Leovy, 2015). Thus, law enforcement efforts at building trust between residents and individual officers, such as through geographically assigned foot patrols and other community-oriented policing activities seem likely to increase V/W participation in crime investigations.

One motivator to CLS participation mentioned only by professionals was resources and support available to V/Ws through their participation. These resources included things like victim compensation and relocation assistance, which operate at the policy level. The reason why V/Ws did not mention these resources and services as a motivator to CLS participation may be because they did not know about them. For instance, 11 of the 20 V/Ws the research team interviewed reported not being offered any resources or supports following their violent incidents. It could also be that the available resources do not outweigh the barriers to CLS participation. In fact, the professionals interviewed in this study described additional resources as an important need to increase V/W participation.

Surprisingly, most V/Ws reported not receiving any follow-up after their initial statement to police about their incidents. Many said they would have liked to have received information about what became of the incident, including whether someone was arrested. A recommendation for law enforcement is to improve communication with V/Ws. Many V/Ws would appreciate knowing what happened because of the incident. This could provide peace of mind if an arrest was made, or allow the V/W to know if the case was closed for another reason, thereby providing closure for the V/W. Furthermore, recontacting V/Ws could provide valuable investigative information. It is common for V/Ws not to recall information at the time of a traumatic incident, but details may surface later, which could be provided to law enforcement later if the V/Ws is recontacted. It is important not to rely exclusively on V/Ws to initiate recontact with law enforcement. V/Ws may have lost contact information of the officer, the officer may no longer be with the department, or the V/W may think the information would not be useful. Furthermore, reasons for V/W non-participation may change over time. Initially reluctant V/Ws may become more willing to participate over time. Therefore, additional contact attempts would allow law enforcement to reassess a V/W’s willingness to participate. As such, law enforcement should make it a point to recontact V/Ws after the initial statement.

Relatedly, most V/Ws were not offered any resources or support following the incident. These are areas where CLS professionals can improve their response by providing more consistent communication and follow-up with V/Ws and making sure that V/Ws are connected with resources after the traumatic experience, if those resources exist. Many CLS professionals expressed frustration with the siloed nature of the CLS system and acknowledged that V/Ws could be better supported through a continuum of care that allows V/Ws to experience warm handoffs between agencies and to make sure that support and resources are offered as soon as possible. CLS professionals viewed victim advocate positions as extremely helpful, but those positions are not always available within CLS agencies or at all stages of the CLS. The value of having a trusted person within the CLS that can connect with V/Ws was emphasized by V/Ws as well. Thus, CLS agencies should have victim advocates on staff, if possible, to serve V/Ws of the most severe forms of community violence. These positions can both support V/Ws and encourage their participation in the CLS by building trust and through continued engagement, often in ways that detectives cannot.

A final need worth emphasizing is the call from the professionals to increase coordination and collaboration between agencies in the CLS. This group mentioned that the siloed nature of the CLS is a barrier to V/W participation and described increased collaboration between agencies in the CLS as a need for increasing V/W participation. For example, they described the importance of warm handoffs between police departments and prosecutors’ offices, coordination between service providers, and multidisciplinary teams to help meet the needs of V/Ws and sustain their participation over time. Furthermore, it may be worthwhile to consider how community-based service professionals who exist outside of the formal CLS may be helpful to increase V/W participation and provide resources. Many V/Ws are distrustful of formal agencies. Therefore, community-based organizations with professionals who can meet V/Ws where they are and relate to V/Ws based on shared experiences may be able to connect with V/Ws and then vouch for CLS agencies or specific personnel to help a V/W participate in the CLS. These community-based organizations can be folded into multidisciplinary approaches that include broader CLS actors to help facilitate V/W participation.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, the sample of CLS and community-based professionals and recent V/Ws of severe community violence reside in one area, the Piedmont Triad region of NC. Thus, this study’s findings may not generalize to other areas of the country. However, it is worth noting that many of the study’s findings align with findings from studies conducted in other cities using different samples. Still, readers should be careful in generalizing these findings to different geographical areas. Another limitation related to the study’s external validity is that the sample was selected based on convenience and thus is not representative of all severe community violence V/Ws and professionals in the area. In fact, the sample overrepresents the experiences and perspectives of older V/Ws given that most victims of severe violence are young adults (Thompson & Tapp, 2022, Table 3). Regarding internal validity, the research team asked V/Ws to reflect on experiences with severe community violence in the past 5 years. For more dated incidents, it is possible that participants could not accurately describe their experiences or attitudes at the time. The average time since the incident that V/Ws described was 1.7 years.

Another limitation was that only one V/W in our sample testified in court about the incident. Therefore, we were unable to capture any nuances in that experience compared to other forms of CLS participation like speaking to a police officer or detective about the incident. The fact that only one V/W progressed through the CLS to a point of participation in court proceedings is not surprising given the many barriers to participation that V/Ws who experience community violence face and because many incidents of community violence are never reported or otherwise become to known to the CLS. In this study, 33 percent of the incidents discussed by V/Ws never became known to law enforcement.

Despite these limitations, this study provides an important understanding of issues facing V/Ws in participating in the CLS following severe acts of community violence and their needs and the needs of the CLS in increasing and improving participation in these cases. This study pointed out important areas of overlap between the two groups in the barriers and motivators to CLS participation and the policies and practices needed to address current gaps. These findings should inform policymakers, CLS organizations, and community organizations in the Piedmont Triad region of NC, and perhaps other places, about how to develop programs and practices to better support and protect V/Ws and improve trust between the police and residents of high-crime areas. As discussed, these changes are likely to increase CLS participation and address sources of unresolved trauma in their communities, thereby improving community safety, well-being, and justice.