Introduction

For more than a decade, studies have reinforced the importance of engaging communities that are being researched or evaluated in the process (Graham et al., 2016; Taffere et al., 2024). Furthermore, community engagement in research is often viewed as a continuum with community outreach and some community involvement at one end and bidirectional collaboration—which entails shared leadership and final decision-making remaining at the community level—at the other end (Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium et al., 2015). Bidirectional community collaboration has been shown to generate better-informed research and evaluation outcomes, particularly when engaging disadvantaged or minoritized communities. However, engagement must be tailored to the community. Thus, bidirectional collaborations with Native Nations and Native American populations must be thoughtful and recognize the important role of Tribal sovereignty.

Why Are Native Nations Unique?

Native Nations retain a unique, government-to-government relationship with the United States government, which has been reaffirmed by treaties, the US Constitution, federal laws, and Supreme Court decisions. Each Native Nation has its own governance structures, laws, and infrastructure aimed at operating effectively to provide services for the Nation and its citizens. This status is not based on race or ethnicity; it is based on their inherent sovereign status. Moreover, this status is reinforced by worldwide recognition that Indigenous Peoples have the right to self-govern, as outlined and agreed upon in the 2007 United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (United Nations General Assembly, 2007).

Native Americans are a heterogeneous group comprising 574 federally recognized Tribes (as of December 11, 2024; Indian Entities Recognized, 2024) and numerous state-recognized and unrecognized Tribes.1 Their uniqueness requires distinct cultural awareness, sensitivity, and knowledge of each Nation’s laws and policies. Tribal members are citizens of three sovereigns: their Tribe, the United States, and the state in which they reside (National Congress of American Indians, 2020). Native Americans are a diverse population, each with their own culture, traditions, and history, and many Tribes have their own language(s) or dialect(s).

For research and evaluation, a Nation’s data governance is tied to their sovereignty. In colloquial terms, Native Nations have the right to adopt their own laws to maintain ownership of and control their data (Carroll et al., 2019; Cobb, 2005; Sorenson, 2017). Thus, Native Nations must have critical leadership and decision-making roles in the development of a research and evaluation agenda that involves their communities; data collection processes associated with this agenda; and the data collected from any efforts that involve their citizens, communities, culture and language, lands and nonhuman relations, and governments.

Despite Native Nations’ longstanding rights to Indigenous data sovereignty, outside entities have exploited these Nations for research for decades. In 1970, for example, Indian Health Service physicians responding to the Family Planning Services and Population Research Act sterilized 25 percent of Native American women who were of childbearing age. These sterilizations were coerced and, in some cases, conducted without patients’ knowledge or understanding of the procedure’s implications (Lawrence, 2000; Luker, 2014; Torpy, 2000). Nearly a decade later, in 1979, researchers who participated in the Barrow, Alaska, alcohol study shared findings externally with academics and the news media before sharing them with the Alaska Native communities that participated in the study. As a result, the Inupiat Alaskan Native community engaged in this study was mischaracterized, and researchers and city-level health practitioners misunderstood the research findings (Foulks, 1989). As a result, Native Nations’ history of exploitation has led to mistrust of researchers and research more generally.

More recently, in 2010, the Havasupai Tribe sued the Arizona Board of Regents, which ended in a 5-year settlement in 2015. The basis for this case was the misuse of blood samples from Havasupai Tribal members by Arizona State University researchers in the 1990s. These researchers collected blood samples from Tribal members and indicated that it was for diabetes research but later used them for further studies in anthropology, nutrition, and genetics. This pivotal court case prompted changes in research regulation by Native Nations—particularly in Arizona—to include protocols and policies aimed at preventing similar misconduct (Orr et al., 2021; Tom, 2021). Many Native Nations developed their own research policies and mechanisms for regulating research within their jurisdictions and among their citizens. Alongside these Tribal initiatives, the Arizona Board of Regents adopted Policy 1-118, which outlines the requirements for research-related Tribal consultation. Specifically, the policy acknowledges that “…laws that protect individual participants in research may not be sufficient to protect the interests of a sovereign [T]ribe that could be affected by research” (University of Arizona, 2016, p. 2). Additionally, this policy, and the Havasupai case in general, motivated the University of Arizona to develop and enact its own institution-specific Tribal consultation policy in September 2023 (University of Arizona, 2023).

Over the past 20 years, the Indigenous data governance movement has made great strides. At its foundation are organizations, such as the Native Nations Institute (NNI) and the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance, and frameworks, such as the Collective benefit, Authority to control, Responsibility, and Ethics (CARE) Principles, that offer guidance and resources on how to uphold Indigenous data governance among Native Nations. These seminal resources provide approaches to collaborating with Native Nations. At the same time, there remains limited literature describing the approach non-Indigenous organizations can take to foster bidirectional collaboration with Native Nations.

This coauthored article from NNI at the University of Arizona and RTI International aims to (1) summarize approaches non-Indigenous organizations can take to foster bidirectional collaborations around research and evaluating initiatives with Native Nations and (2) share examples of bidirectional collaborations with Native Nations and demonstrate how these examples reinforce the suggestions we put forth. The suggestions outline helpful considerations for both initial collaborations and those already working with Native Nations in research and evaluation. Lastly, we note that this article, though acknowledging that Indigenous communities and Native Nations exist throughout the world, focuses on Indigenous individuals in the United States and includes American Indian and Alaska Native peoples only.

Approaches to Foster Bidirectional Collaboration with Native Nations

For nearly 25 years, the NNI at the University of Arizona has been committed to strengthening Indigenous governance and raising awareness about the important processes, approaches, and considerations individuals can take when partnering with Native Nations. Through their work and that of other Indigenous colleagues, NNI suggests the following approaches for non-Indigenous individuals and organizations to foster bilateral collaborations and respectful engagement with Native Nations. (To learn more about NNI, please visit https://nni.arizona.edu.)

When initiating collaborations with a Native Nation, acknowledge and understand the distinctiveness of each Native Nation in the United States. Native Nations have their own language, culture, knowledge systems, and governance structure. Thus, researchers and organizations hoping to collaborate with these Nations must take the time to learn about the Native Nation and their community, respect their sovereignty and unique governmental structure, and approach them with the goal of bilateral collaboration in mind.

-

Before any research or project begins, establish a strong bilateral relationship with a Native Nation that will grow over time. To forge lasting relationships with partner Native Nations, individuals must be committed to understanding each other’s government or organization, policies, culture, and situations, which can result in lasting partnerships that go beyond a stand-alone project. Some tips include the following:

Be respectful, be yourself, and be patient. Figure 1 summarizes that “What you say (or promise)” plus “your actual actions” will determine the level of respect and trust you earn from Native Nations and other community members.

Discuss and create capacity-sharing initiatives to build internal capacity of the partners. Experience has demonstrated that adjacent communities, the state, the country, and people benefit when Native Nations thrive.

i. Both partners will mutually benefit from a partnership that 1) begins well in advance of initiating a project and continues throughout and after the project ends; and 2) allows individuals from the Native Nation to serve as leaders and decision-makers in the project. It is not uncommon to expect 6 months to a year in advance for approval, but the time frame is highly variable among Native Nations.

ii. For example, Native Nations have their own priorities and need partners that can respectfully understand their priorities and any research to be aligned with those needs. Too often, researchers engage Native Nations in a project that they already have in mind, have a project developed before consulting with the Native Nation, or assume they know what the community needs. These approaches do not offer Native Nations the opportunity to guide the research based on their own priorities or needs. Thus, initial relationship building with Native Nations must begin with commitments to listen, efforts to understand, and discussions about the priorities and concerns of the Native Nation(s).

When engaging in discussions and planning with Native Nations, consider the following key questions:

i. What are the needs of the Native Nation?

ii. What is the Native Nation’s process for research approval?

iii. What is the role of the Native Nation in the potential project?

iv. How will information that is part of this project be communicated back to the individuals that are part of the Native Nation?

v. How will information that is generated from this project be used?

vi. How will this project provide opportunities to build capacity within the Native Nation?

Figure 1.

328058Keys for Native Nation relationship building

Source: Diagram reprinted courtesy of the Native Nations Institute, University of Arizona.

3. Recognize that the Native Nation has the rights to decline participation and regulate research activities. Many Native Nations are taking control over governing their data collection through laws, codes, policies, and reviewing bodies, such as a type of Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Research Review Committee. This approach aligns with the principle that “Indigenous data sovereignty asserts the rights of Native [N]ations and Indigenous Peoples to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their own data. Indigenous data sovereignty derives from [T]ribes’ inherent right to govern their peoples, lands, and resources” (Carroll & Martinez, 2019, p. 1). Even if a Native Nation does not have an IRB, they still maintain the authority and ability to regulate research activities, including publications, that involve their citizens. This can also extend to nonhuman subjects in research projects. Thus, receiving approval from the appropriate authority before commencing a research project is not only important but also required.

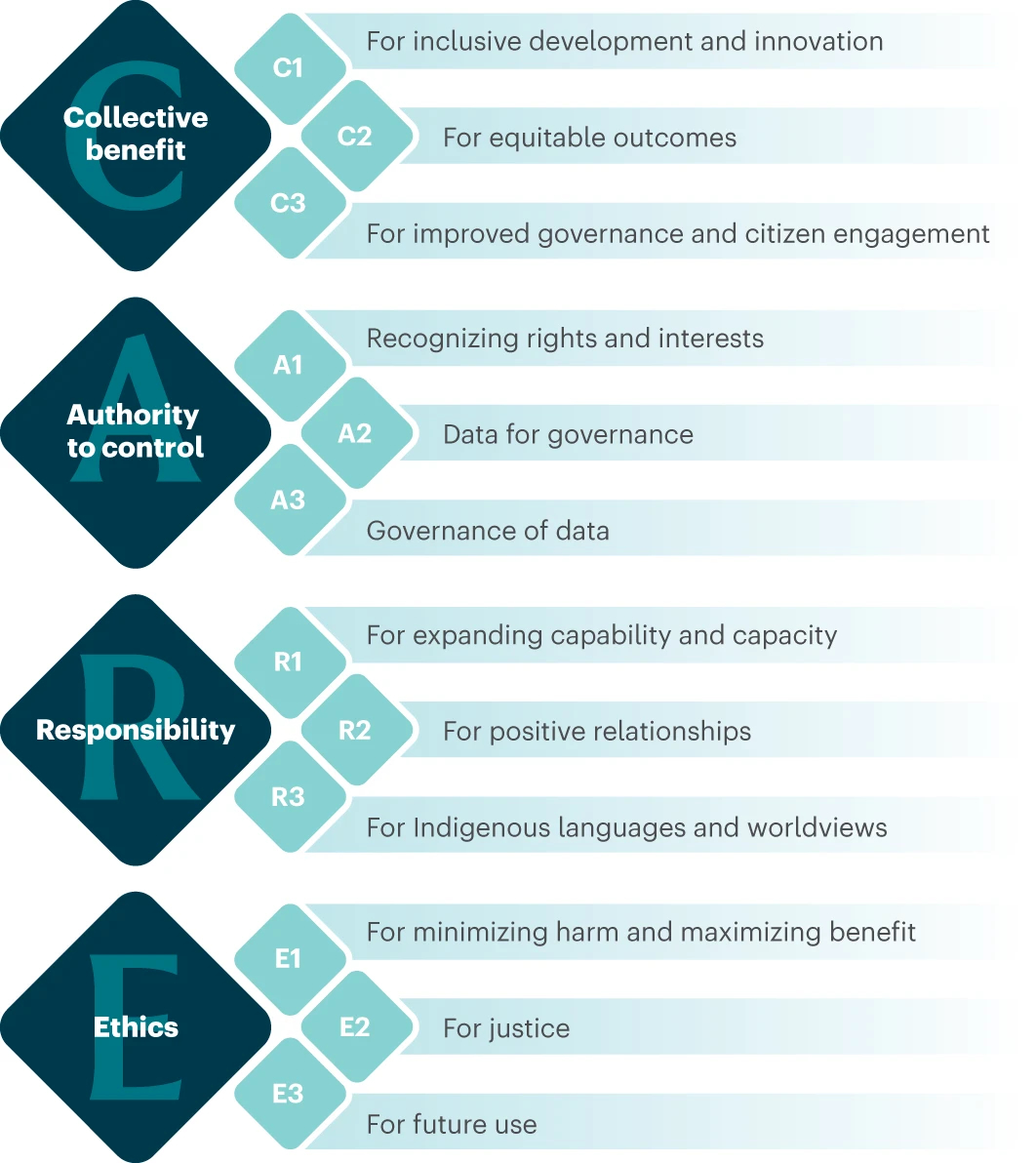

4. Consider incorporating the CARE Principles into project plans and discussions. Among Native Nations, the “Common Rule” (Protection of Human Subjects, 2018) is not adequate to protect and promote Native Nations’ interests when it comes to research. In 2018, the CARE Principles were drafted by “Indigenous and allied academics and practitioners” (Carroll et al., 2020, p. 4). These principles reflect the importance of relationship building and reinforce recommendation 2. Figure 2 illustrates the subcomponents of each principle, with Collective benefit focusing on inclusive development and innovation, improved governance and citizen engagement, and equitable outcomes. Collaborative researchers honor the Native Nation’s Authority to control data collection and research shared. Further, collaborative researchers engage Native Nations with Responsibility by fostering positive relationships, working to expand capacity and capabilities of individuals from Native Nations, and integrating Indigenous languages and worldviews into their work. Lastly, the CARE Principles emphasize the need to engage Native Nations with Ethics so that benefits to the communities are maximized and harms are minimized in an effort to provide justice and foster future partnership and use of the data.

Figure 2.

328059CARE Principles

Source: Diagram reprinted courtesy of Carroll et al. (2020). Carroll et al. (2020) is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC-BY 4.0).

-

5. Take advantage of training to enhance your Tribal community engagement skillset. Making a personal investment in learning about your Indigenous partners can demonstrate your commitment to incorporating an orientation to Native American perspectives in your work, as demonstrated by the following three examples:

Attend the NNI/University of Arizona’s Native Know-How Seminar/Webinar (https://nni.arizona.edu/nkh). Designed to promote a better understanding of the culture and governments of Native Nations, this seminar will help non-Indigenous professionals and organizations create thriving working relationships and partnerships with Tribes and Tribal citizens. Topics include primers on Native Nations, Tribal governments, and their decision-makers and tips to strengthen relationships.

Complete the Research with Native American Communities Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI) training (https://about.citiprogram.org/course/research-with-native-american-communities-important-considerations-when-applying-federal-regulations/), a specialized module within the CITI program designed to educate researchers on the unique ethical considerations and protocols required when conducting research involving Native American populations, ensuring culturally sensitive and respectful practices are followed throughout the research process. Federal regulations require key research personnel be trained in human subjects research. Native Nations with research policies may require proof of such training, as it is viewed as a common standard of responsible research.

Consider participating in the Collaboratory for Indigenous Data Governance and visiting their website: https://indigenousdatalab.org/. Since 2019, the Collaboratory has brought together non-Indigenous organizations, universities, communities, and constituents to discuss approaches for strengthening Indigenous data governance. In addition, the Collaboratory explores ways to build community, support thoughtful and grounded engagement of Native Nations, and engage individuals across diverse disciplines.

When both the researcher and the Native Nation take intentional steps to build mutual respect and trust, they lay the foundation for strong, lasting bilateral relationships. These collaborations, in turn, lead to meaningful research outcomes and contribute to the long-term strength of Tribal communities.

6. Develop an institutional policy that outlines staff and research expectations for collaborating with Native Nations. Some non-Indigenous organizations and government agencies have Tribal liaison officers who serve as primary or initial points of contact with Native Nations. These roles aim to ensure that bidirectional collaboration is upheld and that project leadership includes Native Nations members. Not all non-Indigenous organizations have the capacity or the collaboration need for a dedicated staff person. Instead, some non-Indigenous organizations develop policies outlining the specific protocols that must be followed for collaborative engagement with Native Nations. For example, following the Havasupai Tribe’s case, the University of Arizona developed a policy detailing the University’s requirements for researchers hoping to collaborate with Native Nations. These policies could be embedded in the non-Indigenous organization’s IRB or research review processes.

Case Studies of Bidirectional Collaborations with Native Nations

To help non-Indigenous researchers and evaluators conceptualize the process of bidirectional community collaborations with Native Nations, this article presents two case studies of this process. The first case study emerges from an ongoing project in which RTI and Johns Hopkins University are working with the Navajo Nation and the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe (CRST). The second summarizes a project that the University of Arizona is working on with the Navajo Nation.

In 2016, RTI and Johns Hopkins University received funding to serve as the Environmental influences on Child Health Outcomes (ECHO) Program Data Analysis Center (DAC; National Institutes of Health, 2025). The goal of the ECHO Program is to investigate the links between a broad range of early environmental influences and child health and development. In support of that goal, the ECHO DAC provides a secure, central framework to capture and manage longitudinal data and track biospecimens collected on pregnant women and children, as well as a research infrastructure to support data exploration and analyses by DAC and non-DAC analysts alike. As of March 2025, the ECHO Cohort comprised more than 124,000 participants, including 72,000 children ranging in age from birth to 21 years of age.

RTI, working in collaboration with Johns Hopkins University’s Center for Indigenous Health, adopted the Center’s engagement framework, which prioritizes Indigenous-led partnerships, cultural grounding, transparent communications, and respectful research ethics (Center for Indigenous Health, n.d.). Furthermore, recognizing that Native Nations have the right to decline participation in the ECHO DAC study, the project approached the Navajo Nation and the CRST as Native Nations to determine whether they were willing to participate in the study. The engagement began with discussions that progressed into bidirectional collaboration with the Navajo Nation first. From there, an agreement with the Navajo Nation was created that respects cultural beliefs, Tribal sovereignty, and community values. This agreement also ensures that the research will minimize harm to the Navajo Nation, especially the children who participate in the study, and aim to maximize benefits by identifying environmental causes of morbidity and mortality among children. It is the first Tribal data sharing agreement for a nationwide research consortium, and it laid the groundwork for discussion with CRST, a second Tribal Nation considering participation.

In 2024, representatives from Avera Research Institute—an organization in South Dakota with a long history of partnering with Tribal communities and organization—and Missouri Breaks Industries Research—an American Indian–owned research institute located in Eagle Butte—began working with the National Institutes of Health and the ECHO Consortium to understand the considerations and processes in CRST for a potential data use agreement acknowledging Tribal data sovereignty. The result was a data use agreement that respects CRST data policies and upholds their Tribal sovereignty. Although each agreement created with Tribes is unique, these agreements do have the common recognition that Tribes ultimately own their Tribal members’ data; therefore, Tribes must be able to access the data, and data can only be shared with an external audience after the Tribes provide explicit approval. For the Navajo Nation, this means that the data are de-identified (i.e., no real dates and no geographic locations) and stored in a database on a separate server only accessible by ECHO DAC and Navajo Birth Cohort Study analysts. For CRST, the data are similarly de-identified and protected but shared in a common ECHO DAC database accessible by the ECHO Consortium.

In 2015, Dr. Karletta Chief (Diné) and Dr. Paloma Beamer of the University of Arizona’s Superfund Research Program initiated the Gold King Mine Spill—Diné Exposure Project after the Gold King Mine spill on August 5, 2015, near Silverton, Colorado. The project aimed to assess exposure of Diné residents in Upper Fruitland New Mexico; Shiprock, New Mexico; and Aneth, Utah, to the mine spill and measure lead and arsenic in river water, sediment, agricultural soil, and irrigation water. Dr. Chief engaged her long-standing relationship with her Tribe, the Navajo Nation, to try to understand their perspectives on the spill. She and her Superfund Research Program colleagues held discussions that focused on community concerns about the potential impacts and exposures the spill might create. They collected these concerns and created dissemination materials, such as fact sheets, aimed at sharing these concerns with the public and engaged the media to amplify these concerns. From these initial efforts, the Navajo Nation collaborated with Dr. Chief and her team to design and help collect data for a study of exposure, risk, and risk perceptions. Furthermore, collaborations with the Navajo Nation and local community leaders at the Native Nation chapter level included extensive efforts to recognize Indigenous knowledge, include community voice, encourage Tribal participation, build capacity, and promote cross-cultural teaching and learning. Long-term efforts focused on identifying environmental impacts and conducting community outreach to assess the spill’s impacts on irrigation disruption and health. This research is ongoing.

The benefits from these examples of bidirectional community collaborations include community buy-in and participation, continued support, and partnerships that focus on addressing the long-term needs of and vision for the community, which will, in turn, enhance mutual outcomes.

Conclusion

During the past 2 decades, bidirectional collaborations between Native Nations and non-Indigenous partners have increased, and resources and literature emphasizing the importance of Indigenous data governance have grown significantly. Presently, collaborations with Native Nations can be informed by the CARE Principles, successful examples of bidirectional collaborations, trainings and resources provided by NNI, and non-Indigenous organizations’ internal policies. These approaches will hopefully allow future researchers to avoid the missteps of the past and allow Native Nations to collaborate on research and projects that enrich their communities and citizens.