It’s easy for the tiny mosquito to fly under the radar. But its ability to rapidly spread deadly and disabling diseases to humans like malaria, lymphatic filariasis, Zika, West Nile virus, chikungunya, yellow fever, and dengue make it an incredibly dangerous adversary.

In honor of World Mosquito Day, we broke down 10 facts about the world’s deadliest animal, and the important work being done to defeat the diseases it transmits.

1. A Nobel Prize worthy discovery

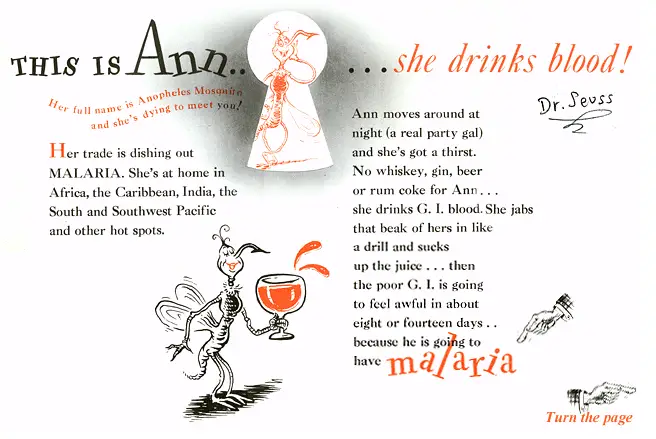

While dissecting the stomach tissue of a mosquito on August 20, 1897, Sir Ronald Ross discovered the malaria parasite inside. He soon proved that the female Anopheles mosquito is the animal responsible for transmitting malaria. Now, August 20th is known as World Mosquito Day to commemorate Sir Ronald Ross’ pivotal discovery. We now know that several Plasmodium species transmitted by mosquitoes can cause human malaria. Plasmodium falciparum malaria—the deadliest—is most common in sub-Saharan Africa, where it causes more than 400,000 deaths a year, the majority of whom are children under five.

2. Tiny killers and killjoys

Though only female mosquitoes feed on humans, the mosquito remains the deadliest animal in the world. Even today, the mosquito is responsible for over 1 million deaths each year. In addition to spreading deadly diseases like malaria, yellow fever, and dengue, these small insects can have a big impact on a person’s health and wellbeing. For example, mosquitoes spread the parasites that cause lymphatic filariasis (LF), one of the world’s leading causes of disability. Also known as elephantiasis, LF causes swollen limbs, severe pain, and social discrimination among millions of the world’s most vulnerable people.