Tuberculosis (TB) is once again one of the world's leading infectious disease killers, alongside COVID-19. Unlike COVID-19, it's not getting treated like one.

For two and a half years, COVID-19 consumed public health efforts as it became the world’s deadliest infectious disease. With that title, came large investments to fight the disease, leaps in scientific progress, and global collaborative efforts, all demonstrating an immense urgency to squash a disease.For years before COVID-19 emerged, TB held this title, killing more than 4,100 people a day across 129 countries according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Those are similar numbers to COVID-19 during the deadliest days of the pandemic. Since the emergence of COVID-19, TB cases have surged, returning it to the top infectious disease killer spot, but the world’s response struggles to keep up.

To RTI’s TB expert Dr. Doris Rouse, this is no surprise.

Dr. Rouse is the former Vice President of Global Health Technologies at RTI International where she has worked on identifying new TB treatments through public-private partnerships for more than 20 years. In 2019, her team achieved huge success when the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved pretomanid, a treatment identified by Rouse’s team for extensively drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB), making it only the third anti-TB drug approved in the past 30 years.

Reflecting on this progress and the challenges of TB's surge during the COVID-19 pandemic, Rouse chats with RTI's Global Health Security Director Alisha Smith-Arthur about her career and the future of work to end TB.

Smith-Arthur: Why did you get into the global health field? What was it about TB that made you passionate about finding new drugs?

Rouse: I first became aware of TB when I served in the Peace Corps teaching in a rural village in Liberia. I was truly shaken by the scope of the global health challenges I saw there. One of my brightest students suffered from cerebral malaria. He survived but was never the same. So, my commitment to addressing global health gaps really started there.

Then when I came back from the Peace Corps, I focused my career on having an impact in global health – first, working for a pharmaceutical company addressing tropical diseases and then for RTI International focusing on public-private partnerships. Early in my time at RTI, someone at the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) approached me about partnerships to address TB and I really became committed to this issue of bringing together both the public and the private sector, as well as universities and the community, to address the challenges around TB treatments. The outcome was that we won a contract in 1999 to do just exactly that; to find new drugs and create partnerships to move them forward.

One of our first tasks was to work with the NIH and the Rockefeller Foundation to plan an international meeting in Cape Town, South Africa, in February 2000 which led to the Cape Town declaration for global collaboration to develop new TB drugs. We then helped to form a public-private partnership known as the Global Alliance for TB Drug Development (TB Alliance) in 2001 and continue to work with them to this day to develop more effective and affordable new drugs for TB.

SA: You had such a vision at the time around coalition building and aligning what corporations and private sector partners could bring to the table. I can only imagine how much work went into that, and that was even before developing the actual drug. What has the journey been like? What kept you moving?

R: It has been a long journey. We identified pretomanid in 2002. The long development process led to FDA approval in 2019. But what really kept us going was the commitment of the people at the TB Alliance to develop an accessible, available, and affordable drug for all.

In 2007, I went with some colleagues from the TB Alliance to a TB clinic in Cape Town for the first human trials of the drug. We spoke with one of the nurses at the clinic to see how it was going, and she said, ‘this drug really works.’ She said patients come in emaciated, they aren’t eating anything, they have night sweats and are clearly suffering, but after being on this drug for just a few days, they are eating, sleeping through the night.

I still get emotional talking about how clearly excited and hopeful this nurse was. And that’s when I knew we had to keep going. And we did. We crossed the finish line. There were some naysayers and problems early on, but the TB Alliance and RTI were committed to seeing this drug through to FDA approval.

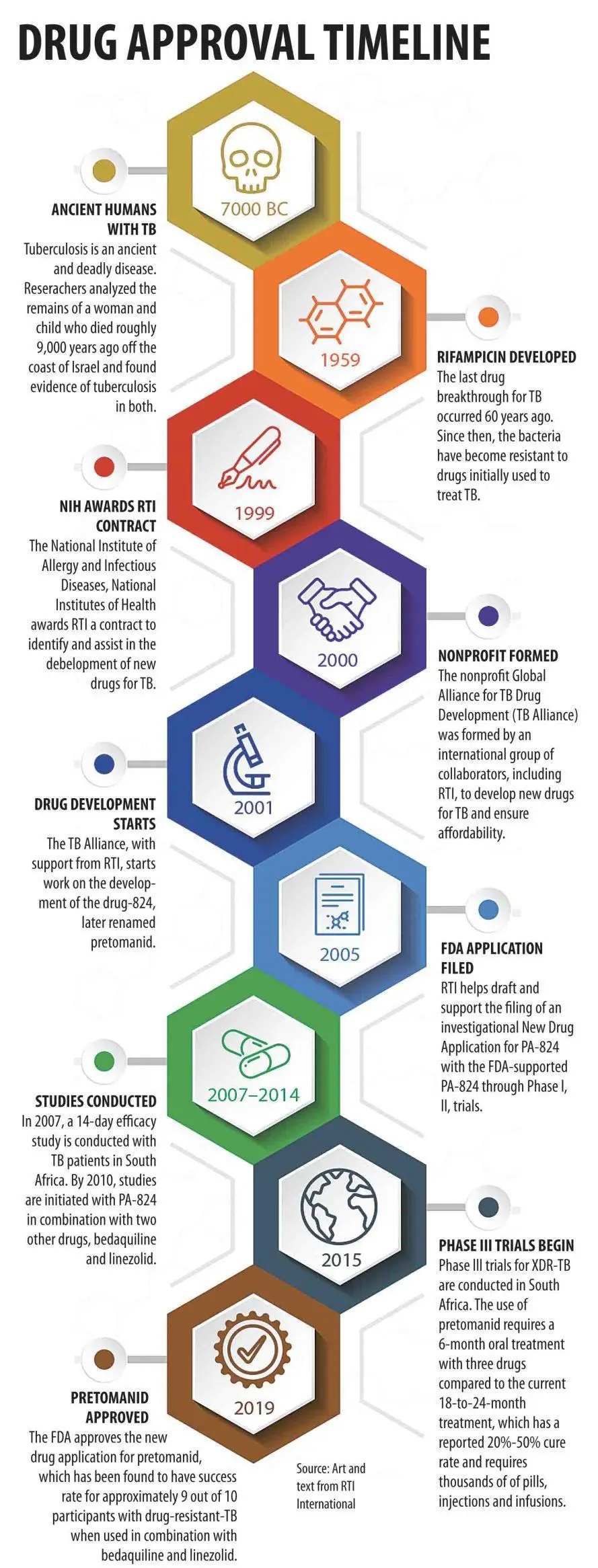

Tuberculosis timeline from early human infection to approval of pretomanid, a new drug to fight TB that took 20 years of development to approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

SA: That gives me goosebumps. I think that moment with a health worker or patient is really what we’re all working towards. So now that it is approved, what does the promise of this new drug mean for patients and communities that are impacted by TB and what still needs to be done?

R: It is a breakthrough but not a standalone breakthrough. I think one of the important aspects of this effort is that it proved the premise that many doubted along the way – that the public and private sectors can indeed come together, develop a new drug, and make it available to the countries that need it at an affordable price. It has led to other public-private partnerships in other therapeutic areas. I really give all the credit to the TB Alliance.

Pretomanid, which is used in combination with two other drugs (Bedaquiline and linezolid), treats drug-resistant TB (XDR-TB) when patients do not improve after receiving three or more standard TB drugs. The previous go-to treatment for XDR-TB required a 18-24 month-long quarantine with a rigorous course of treatment with injections and infusions and about 14,000 pills in total, causing unpleasant side effects and resulting only in a 34% success rate.

This new tuberculosis treatment regimen is more affordable with three oral drugs every day for six months, fewer side effects, and a 90% success rate. It was a breakthrough giving TB patients hope that they would survive. The lengthy and complicated treatment regimens are a major barrier to stopping TB because it is difficult for patients to follow precisely especially as they start to recover and feel better.

From a patient and community perspective, these new TB regimens hold promise for better chances of following the regimen, resulting in reduced drug resistance and improving the whole health system in a country. Also, the community burden, drug costs and cost of having health workers observe patients taking their treatment to ensure they are following the regimen will be substantially reduced.

SA: Stepping back and looking broadly at TB efforts, where do you think we are in terms of control efforts? What more is needed, especially with the disruptions from the COVID-19 pandemic?

R: The good news is the partnerships are continuing not just for new drugs but also new diagnostics.

The disturbing news is that TB cases have risen during the COVID-19 pandemic. There are many root causes for TB, so we need to have collaboration and commitment to strong health systems that can address the underlying issues. One of the underlying issues contributing to tuberculosis is poor nutrition in countries where people are not getting enough to eat, making them more susceptible to infectious diseases. HIV infection is another issue. TB is an opportunistic infection for HIV because your immune system is suppressed, so strengthening the fight against HIV is important for TB as well.

We must also engage the community, not just the patient and make appropriate use of the drugs a norm for being a good community member. If you develop the best drug in the world, but someone is not taking it appropriately, it’s not going to have the impact it could. It really is about engaging the biomedical development community and health care providers in countries, and the families and neighbors of patients in addition to the patients themselves. Communities need to know the importance of their brother or father following the treatment regimen because otherwise, they are going to be infectious and the whole community is going to be at risk of becoming infected.

SA: You’re so right. When I think about how we tackled TB in North America and Western Europe, we forget that it was two things happening in tandem; it was biomedical advances and the ability to find TB and treat it, but it was also improving social and economic factors—better housing and nutrition and reduction of risk factors. What makes you hopeful about where we are in ending TB?

R: I’m very pleased to see the increased emphasis on building capacity in different countries—not just for care of patients, but also in the development of drugs. For example, the Pan-African Consortium for the Evaluation of Antituberculosis Antibiotics (PanACEA) industry-university consortium program is advancing the development of new drugs while also building expanded clinical trial capacity in sub-Saharan Africa which is what we need.

Bilateral and multilateral donors, including USAID, are also setting new commitments to end TB.

It's also very important that solutions have been made widely available at affordable prices. The Global Drug Facility is effective in providing quality treatments and diagnostics at reasonable costs, but we still need more advances in this area.

SA: Any reflections on your work and your experiences over the years? What things are you thankful for? What have you learned that you didn’t expect to learn?

R: Oh, there are many. I am especially appreciative of working with the people at the TB Alliance who are so committed to their work in this nonprofit and working with people globally. I also feel fortunate to be part of RTI. As a global nonprofit research institute, RTI is well positioned to bring public-private partnerships together, because we are a nonprofit and don’t have any bias one direction or the other. We've also worked with the private sector and the public sector as well as universities and other nonprofits, so we know how to work across those different sectors. This unique experience allows us to work with our partners to create smart, shared solutions for a more prosperous and resilient world—one day, hopefully, free of infectious diseases like TB.

RTI International is a global leader in the prevention and control of infectious diseases, including neglected tropical diseases, malaria, tuberculosis, HIV, and emerging infectious diseases like COVID-19. We leverage our expertise in drug discovery and development, community engagement, data science, health systems strengthening, and more to develop innovative approaches to end TB. Learn more about our work in global health.