Introduction

In 2015, about 18 percent of new breast cancer cases (43,446/242,463) were diagnosed in women younger than 50 years; 4 percent (10,679) were in women 18–39 years of age, and 14 percent (32,767) were in women 40–49 years of age (US Cancer Statistics Working Group, 2018). Breast cancer may have different effects on women younger than 50 years compared with women 50 years or older in terms of survivorship, fertility, and familial obligations. Breast cancer screening using mammography is only recommended for older women (starting between 40 and 50 years depending on the specific recommendation or guideline) (Kerlikowske, 2015). Women younger than 50 years have reported greater concerns about their treatment, their survival, and the effects of treatment on fertility and prospects for having children (Park et al., 2018; Partridge et al., 2004).

Breast cancer survivors (women who have received a breast cancer diagnosis) younger than 50 years may want to continue education or employment, and undergoing cancer treatments during this phase of life can put these opportunities on hold (Partridge et al., 2012). To date, employment and financial burden research has primarily focused on breast cancer survivors in specific geographic areas of the United States. Approximately one-quarter of breast cancer survivors in one study experienced a financial decline, attributed at least in part to their breast cancer (Jagsi et al., 2014). This study further reported that many breast cancer survivors retained their jobs to maintain health insurance or found new employment to acquire health insurance benefits (Jagsi et al., 2014). In terms of continuing or returning to work after diagnosis or treatment, respondents were more willing to do so if they perceived their employers as accommodating, and less likely to do so if they perceived employer discrimination on account of their diagnosis (Bouknight et al., 2006).

Although existing studies compare these challenges across age groups, limited information is available about the employment experiences of breast cancer survivors across the entire United States (Jagsi et al., 2014). To fill these gaps in knowledge, we developed a nationwide, web-based survey to collect information on the experiences of breast cancer survivors younger than 50 years at time of first diagnosis. The survey emphasized effects on employment and the financial burden of the disease. The study compared breast cancer survivors first diagnosed at 18–39 years with breast cancer survivors first diagnosed at 40–49 years to explore whether the younger age group would report greater employment and financial burden. We included women up to the age of 50 at diagnosis for this survey, as there is no clear definition of “young” breast cancer survivors. Some studies include only those under 40 years of age at diagnosis; others consider patients under 45 years or even under 50 years of age at diagnosis to be in the young cohort.

Methods

We recruited a convenience sample of breast cancer survivors from two breast cancer interest groups: Living Beyond Breast Cancer and Young Survival Coalition. The interest groups posted announcements on their Facebook pages, invited participants via e-mails, and announced the survey in electronic newsletters. No incentive was provided.

Survey participation was based on interest-group affiliation rather than random sampling methods. Participants were included in the sample if they were female and had been diagnosed with breast cancer between the ages of 18 and 49. Women were ineligible if they had been diagnosed with breast cancer more than 10 years before completing the survey or if they lived in California, Florida, Georgia, or North Carolina and were diagnosed with breast cancer between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2014. These women were excluded because they were targeted for participation in a similar survey using cohorts drawn from cancer registry databases in these four states.

The survey questionnaire was web-based. The questions were informed by past literature surveying cancer patients (Arora et al., 2011; Jagsi et al., 2014; Malin et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2007) and, whenever feasible, used question wording from prior surveys such as the National Health Interview Survey, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, and the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans. We developed the questions in both English and Spanish. To ensure appropriateness and clarity of the questions in the online survey for low-income and low-education respondents, we conducted cognitive testing of the survey in English (nine breast cancer survivors) and in Spanish (eight breast cancer survivors) in Raleigh/Durham, NC; Washington, DC; and Houston, TX.

Overall, the questionnaire contained 66 questions on employment status, insurance status, financial burden of treatment, quality of care, quality of life, cancer history, and demographics, such as the age at first diagnosis, race/ethnicity, marital status, and education. The quality-of-life items were taken directly from the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast Cancer Symptom Index but all other items were adapted from validated tools and refined for our specific sample population. Validated tools that served as sources included the Medicaid Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems and the National Health Interview Survey. We honed each survey item for low-income and low-literacy populations and performed extensive cognitive testing on the draft survey instrument to identify problems with response options before the survey was fielded.

We provided respondents with a list of comorbid conditions, including cardiovascular conditions, circulatory problems, vision issues, depression, migraines, back problems, arthritis, and thyroid problems, and instructed them to select all that applied. A write-in “other” option was also supplied. For the analyses in this study, we calculated a summary comorbidity score (no conditions, one condition, or two or more conditions). Clinical variables examined included stage at diagnosis and type of treatment received; treatments could include surgery, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, hormone therapy, and immunotherapy. Respondents were also asked whether they were undergoing treatment at the time of survey administration.

The survey was conducted via the web nationally from October 2016 through June 2017 and took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The survey probed insurance coverage, type, and experiences, encompassing details on insurance status at the time the survey was conducted (12 months post-diagnosis), at diagnosis, and during the year-long period after diagnosis. Questions about employment status at the time of breast cancer diagnosis included the type of job, hours-per-week worked, and detailed measures of employment before and after cancer diagnosis. Questions also captured any issues maintaining and seeking new employment after breast cancer diagnosis, such as needing to change jobs within a company, moving to a new company for health insurance, staying in a job to keep health insurance, taking time off without pay, retiring early, or quitting a job. Respondents also were asked about the level of support they received from their employers during breast cancer treatment (e.g., whether their employers were aware of their breast cancer diagnosis). In addition, respondents were asked to report on any decline in their financial status caused by their breast cancer diagnosis. Financial decline was measured categorically: “not much,” “a little,” “somewhat,” “quite a bit,” or “very much.”

We used descriptive statistics to compare women first diagnosed between the ages of 18 and 39 with those first diagnosed between the ages of 40 and 49. We used logistic regression to examine factors related to perceived breast cancer–related financial decline. The outcome variable measured the financial impact of the respondent’s breast cancer diagnosis. Responses ranging from “somewhat” to “very much” were coded as 1, while “none,” “not much,” and “a little” were coded as 0. Control variables included age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, marital status, education, employment status, comorbid conditions, stage of diagnosis, and whether the woman was currently receiving breast cancer treatment. We conducted descriptive and regression analyses using Stata (StataCorp, 2017). Statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

A total of 674 respondents provided electronic informed consent and began the surveys (see Figure A.1 in the Appendix). Of these, 258 respondents were excluded from further analysis: 160 completed only a small portion of the survey, 70 did not provide values for key variables, and 28 had been diagnosed with breast cancer more than 10 years before completing the survey. The final study population included 416 respondents.

The demographic characteristics of the two age groups were generally similar (Table 1). In both age groups, more than 80 percent of the survivors were non-Hispanic white, at least 75 percent had either a college or graduate degree, and at least 75 percent were married or had a partner. More than 50 percent of the survivors had two or more comorbid conditions at the time of the survey, and more than 25 percent had one comorbid condition.

Approximately two-thirds of the respondents were in treatment at the time of the survey (Table 1). Survivors 18–39 years of age were more likely to report Stage II, III, or IV breast cancer and to report receiving chemotherapy or immunotherapy. Although more than 90 percent of survivors in both age groups reported receipt of surgery, a higher proportion of survivors 40–49 years of age reported surgery (P = 0.05).

Table 1.

42515Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics by age at diagnosis among survey respondents, 2016–2017

Source: Data were collected from October 2016 through June 2017 under Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval No. 0920–1123 received for the Breast Cancer in Young Women Survey.

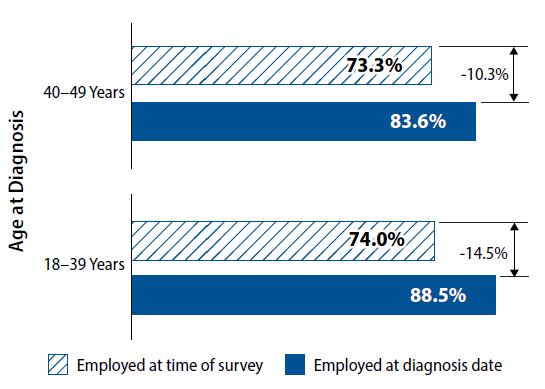

Respondents 18–39 years of age reported a decline in employment; 88.5 percent had been employed at the time of diagnosis, but 74.0 percent were employed at the time of the survey (Figure 1). Women 40–49 years of age experienced a decline in employment from 83.6 percent at the time of diagnosis to 73.3 percent at the time of the survey. These declines were statistically significant for both age groups.

Figure 1.

42519Employment status by age at diagnosis among survey respondents, 2016–2017

Note: Difference in employment status at diagnosis and time of survey are statistically significant for both groups (P = 0.001).

Source: Data were collected October 2016 through June 2017 under Office of Management and Budget approval No. 0920-1123 received for the Breast Cancer in Young Women.

In both age groups, about 10 percent of survivors reported that their employers had not been supportive at the time of first diagnosis (Table 2)

. Among survivors who had been working at time of first diagnosis, the proportion of survivors 18–39 years of age who had quit their job by the time of the survey (14.6 percent) was about three times larger than the proportion of those 40–49 years of age who had done so (4.4 percent) (P < .01). Job performance issues were reported by 55.7 percent of survivors 18–39 years of age and 42.8 percent of survivors 40–49 years of age (P = .02). Overall, about 75 percent of survivors reported that their employment was quite important or very important to their financial standing. Overall, more than half of the breast cancer survivors (54.2 percent) reported a financial decline (see Figure A.2 in the Appendix for descriptive statistics on financial decline by age at diagnosis and treatment status).

Table 2.

42516Employment impacts by age at diagnosis among survey respondents, 2016–2017

Source: Data were collected from October 2016 through June 2017 under Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval No. 0920–1123 received for the Breast Cancer in Young Women Survey.

After adjusting for multiple factors (see Table 3), we found financial decline was not associated with age at diagnosis, race/ethnicity, education, or receipt of treatment at the time the survey was completed. Financial decline was significantly more likely if the survivor had reported one (odds ratio [OR], 2.36; 95 percent confidence interval [CI], 1.27–4.39) or two or more (OR, 3.21; 95 percent CI, 1.83–5.63) comorbid conditions, compared with no comorbid conditions. Financial decline was also significantly more likely for those whose first diagnosis was at Stage II (OR, 2.04; 95 percent CI, 1.24–3.33) or at Stage III or IV (OR, 3.51; 95 percent CI, 2.01–6.13), compared with Stage 0 or I. Financial decline was significantly less likely among survivors who were married or who had a partner (OR, 0.51; 95 percent CI, 0.30–0.88) and among survivors who had a job (OR, 0.59; 95 percent CI, 0.3–0.98).

Table 3.

42517Multivariate regression analysis of factors potentially related to financial decline among young women with breast cancer, 2016–2017

Notes: OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval.

Source: Data were collected from October 2016 through June 2017 under Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval No. 0920–1123 received for the Breast Cancer in Young Women Survey.

Discussion

Compared with breast cancer survivors 40–49 years of age, survivors 18–39 years of age were more likely to report Stage II, III, or IV breast cancer at time of first diagnosis, that they had quit their job, and that they had job performance issues. Financial decline was not associated with age group but was associated with late-stage disease and comorbidity.

Few prior studies have specifically addressed the financial burden of breast cancer among younger women (Allaire et al., 2016, 2017; Ekwueme et al., 2016; Trogdon et al., 2017). The current study findings in younger breast cancer survivors are consistent with prior studies on the economic impact on breast cancer survivors of all age groups (such as job discontinuation and decreased working hours) (Blinder et al., 2013, 2017; Glare et al., 2017; Hassett et al., 2009; Høyer et al., 2012; Jagsi et al., 2017; Neumark et al., 2015). Several studies of breast cancer survivors of all ages have documented a substantial employment disruption over the course of the diagnosis and treatment process (Høyer et al., 2012; Jagsi et al., 2017). Being employed improves the quality of life of cancer patients in numerous ways; for example, it is a source of income, health insurance, social interactions, and distraction. Protracted breast cancer treatment and recovery can disrupt patient employment and affect other aspects of patient quality of life (Brown et al., 2016; Jagsi et al., 2017; Saito et al., 2014; Trogdon et al., 2016).

Although all young women diagnosed with breast cancer experienced a decline in employment, the current study also found a somewhat larger decline in employment after a breast cancer diagnosis for women 18–39 years of age (14.5 percent) than those 40–49 years of age (10.3 percent). Furthermore, compared with women 40–49 years of age, more women 18–39 years of age struggled with job performance, avoided changing jobs to keep their health insurance, changed jobs within their company, or quit working altogether. Further research is needed to assess whether younger women, who may not be as established in their careers and therefore have less seniority than older women, have limited ability to negotiate a more-flexible work schedule with employers. This study did not directly evaluate the role of sick leave in employment. Other studies have suggested that having sick leave available is associated with a greater likelihood of reemployment in breast cancer survivors (Barmby et al., 2002; Bouknight et al., 2006).

The regression analysis found that financial decline was associated with late-stage disease and comorbidity but found no statistically significant difference by age group. Financial decline could result from breast cancer–related unemployment or reduced working hours and associated loss of income and employment-based insurance (Saito et al., 2014). Our findings suggest that breast cancer survivors who were married or had a partner and were employed were less likely to experience financial hardship, whereas survivors who had comorbidities and were diagnosed with late-stage disease were more likely to experience financial decline. Given these findings, decision makers may want to consider offering tailored chronic disease management services when seeking to reduce the financial burden for breast cancer survivors. These services could include patient navigation support to help cope with comorbidities and counseling to help with financial planning. Furthermore, research is also needed on optimal approaches to identify breast cancers at an earlier stage in younger women, potentially including education on breast health awareness and ways to monitor changes in their breast, as this may also reduce the financial hardship faced by these survivors. Providing education to both young women and their health care providers may lead to better understanding of breast cancer symptoms and may reduce the delays in diagnosis often experienced by these young women.

A key strength of this study is its focus on breast cancer survivors younger than 49 years. A potential limitation is the small sample size of the study, which may have limited our power in assessing differences among breast cancer survivors by age group. Another limitation is potential selection bias, as respondents volunteered to take this web-based survey. Given the accrual via web-based sources (Facebook, email, etc.), there is a strong bias toward women with access to these resources, as reflected in the relatively high education level of our sample. This may have implications for the generalizability of our results to the broader cohort of young women in the United States diagnosed with breast cancer. In general, the convenience sampling approach limited our ability to make statistical inferences. It is possible that only women who experienced barriers chose to complete the survey, but we were unable to verify the direction of any potential bias. We were also unable to provide the response rate for our survey, as we did not target a specific cohort of women diagnosed with breast cancer before the age of 50. All information on clinical diagnosis related to breast cancer was self-reported and thus also could be subject to recall bias.

This study adds to the limited literature on the impacts of breast cancer diagnosis on the employment and financial well-being of young women. Most breast cancers are diagnosed in women older than 40 years, but the financial burden of breast cancer related to employment appears to be high among young survivors 18–39 years of age. Increased understanding of the negative impacts on employment and financial resources of young breast cancer patients could inform interventions, such as financial counseling, to help survivors better cope and thrive after their breast cancer diagnosis. Because the results of this web-based survey may have been biased by the self-selection of participants, additional studies with randomly selected participants may be useful in confirming the conclusions on the financial impact of breast cancer diagnosis among young women.

Conclusion

Compared with breast cancer survivors 40–49 years of age, survivors 18–39 years of age were more likely to report late-stage breast cancer at the time of first diagnosis. Financial decline was strongly associated with late-stage disease. They also experienced more negative employment consequences: they were more likely to quit their job, and they had higher levels of job performance issues. The findings from this study can be used to inform discussions by policy makers on ways to reduce the financial impact of breast cancer diagnosis and treatment on young women. Research is needed on support strategies such as more-comprehensive insurance coverage with limits on out-of-pocket payments and other policies that enable young breast cancer patients to maintain job security while they undergo and recover from treatment.

Acknowledgments

The findings in this manuscript are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Funding support for RTI staff was provided by the CDC (Contract N0. 200-2008-27958 Task 48, to RTI International).

Data were collected October 2016 through June 2017 under Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approval No. 0920-1123 received for the Breast Cancer in Young Women Survey.

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Cover photo: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is working to increase awareness of breast cancer and improve the health and quality of life of young breast cancer survivors and young women who are at higher risk of getting breast cancer. The Bring Your Brave campaign shares real stories about young women whose lives have been affected by breast cancer (pictured, left to right: Carletta; Joyce Turner, MSC, CGC (a genetic counselor); and Cara). For more information visit https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/breast/young_women/.

Photographer: Tyler Mallory

Art Director: Shannon Benson

Creative Director: Allyson Hummel