Almost half of Americans have experienced the incarceration of an immediate family member, and one in five women have had an incarcerated intimate partner (Enns et al., 2019). Formerly incarcerated men and their partners report extraordinarily high rates of partner violence—often 10-fold those observed in the general population (Breiding et al., 2014; McKay et al., 2018; Wildeman, 2012).

Understanding the Context for Partner Violence After Reentry

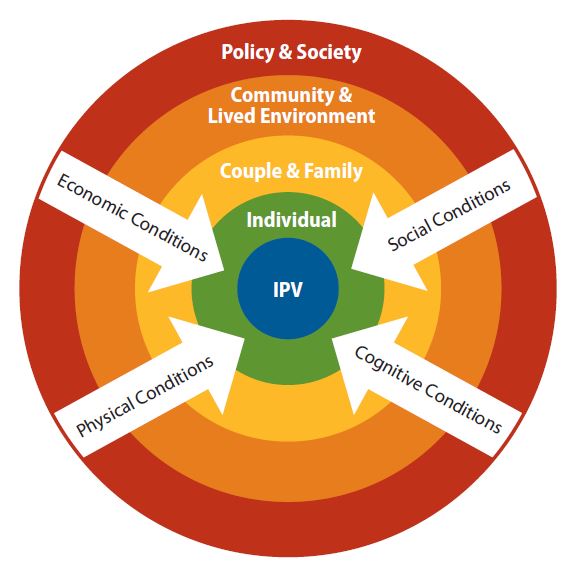

Applying the Social Ecological Framework to qualitative interview data on post-prison partner violence from reentering men and their partners, we identified contextual influences on partner violence at multiple ecological levels. Narratives suggested that violence arose amid the adverse cognitive, physical, and social conditions that surrounded couples’ intimate and coparenting relationships during the period of reentry from prison. These included (1) poverty and economic exclusion, (2) deteriorated communication and lack of information, (3) exposure to violence, and (4) social isolation and disempowerment. Results suggest that systemic change, across ecological levels, is needed to prevent violence in couples reuniting after incarceration.

Understanding the Context: The Post-Incarceration Partner Violence Study

Understanding the contexts in which violence arises is critical to effective prevention and response (Bent-Goodley & Williams, 2004; Chan et al., 2016; Groblewski, 2013; Williams, 2007; Williams et al., 2008). To fill this gap, RTI researchers analyzed qualitative data from 167 participants in the Multi-site Family Study on Parenting, Partnering and Incarceration. The Post-Incarceration Partner Violence Study enrolled men incarcerated in state prisons and their female partners and interviewed them around the time of the male partner’s return from prison (e.g., “reentry”). Using modified grounded theory (Birks & Mills, 2015), the team applied inductive and deductive codes to deidentified, verbatim transcripts in ATLAS.ti; reviewed and themed the data gleaned from Boolean-type queries; and collectively and iteratively developed analytic memos on each theme.

Figure 1.

42722Social-ecological context for post-prison intimate partner violence

Note: This framework applies data from the Multi-Site Family Study on Incarceration, Parenting and Partnering to adapt the general social-ecological framework for intimate partner violence proposed by Bell and Naugle (2008).

The Social-Ecological Framework suggests that contextual influences at multiple ecological levels influence individuals’ experiences of violence (Figure 1) (Assari, 2013; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002). Multi-site Family Study participants perceived four distinct pathways by which the distal contexts of their lives (indicated by the red “Policy & Society” ring and orange “Community & Lived Environment” ring) shaped more proximal contexts (indicated by the yellow “Couple & Family” ring and green “Individual” ring), which in turn shaped their experiences of partner violence. These pathways related to the economic, cognitive, physical, and social conditions surrounding their relationships.

Economic Conditions: Exclusion and Poverty

Consistent with prior research (Schwartz-Soicher et al., 2011; Uggen et al., 2014; Visher et al., 2011; Western et al., 2001; Western & Pettit, 2010; Wildeman & Western, 2010), economic conditions placed constant strain on relationships between reentering men and their partners. At the individual level, reentering partners struggled to secure income from legal employment—which, at the couple and family level, brought household financial strain and high-stakes conflicts over the shortage of money to meet basic needs. These strains were shaped by community-level shortages of legal employment and a density of opportunity for criminalized activity—which participants saw as perpetuated at the societal and policy levels by conviction-related employment barriers, a lack of institutional support for post-prison workforce reintegration, and fines and fees imposed by the criminal justice system. They were further exacerbated by societal-level gender norms positioning men as family economic providers (an unattainable scenario for most participating couples). In this environment, financial strain and conflict sometimes escalated into the use of violence.

Cognitive Conditions: Deteriorated Communication and Lack of Information

Like many couples reuniting after an incarceration (Comfort, 2008; Fishman, 1990; Freeland Braun, 2012; Hairston & Oliver, 2006, 2011; Oliver & Hairston, 2008), Multi-site Family Study participants were affected by deteriorated communication and an erosion of mutual awareness of one another’s lives during imprisonment. Shaped at the policy level by the imposition of physical separation during incarceration and institutional and policy barriers to open dialog, many couples lacked knowledge of important aspects of one another’s lives during incarceration. When couples resumed unimpeded communication upon the male partner’s release, they often experienced high-intensity, recurrent conflicts around one or both partners’ actual or perceived intimacy with others, household routines, and divisions of labor. These conditions made it difficult to maintain stable routines or agreements that could facilitate secure, interdependent collaboration. Instead, one or both partners sometimes attempted to control the other’s behavior using manipulative or abusive tactics.

Physical Conditions: Exposure to Violence

Multi-site Family Study participants often described partner violence arising in the context of one or both couple members’ individual mental health symptoms, particularly post-traumatic stress (including hypervigilance and dissociation) and other forms of traumatic adaptation; struggles with addiction; and unrelenting anger at their partners and their larger circumstances, particularly around the ways that encounters with the criminal justice system had changed their families and life prospects (Hampton et al., 2003; Oliver & Hairston, 2008).

Participants described struggles with addiction as arising in community environments where highly addictive substances were readily available (as documented in prior research, Cunradi et al., 2011, 2014) and exposures to violence and trauma were common. Violence and trauma exposures were gendered, with men more often relaying experiences with street and prison violence, and women more often describing prior sexual violence and partner violence victimization as well as traumatic pregnancy, birth, and parenting experiences (e.g., loss of custody).

Other community-level dynamics, including a perceived lack of protection from the criminal justice system or other government entities and a sense of harsh and inconsistent implementation of criminal justice policies (including violent police-civilian encounters) contributed to a sense of overriding physical vulnerability and the need for constant defense. Partners reported heightened reactivity and sometimes had difficulty responding nonaggressively to each other in charged situations.

Safe Return: A Context-Responsive Intimate Partner Violence Intervention for Reentering African American Men and Their Partners

The Safe Return Initiative brought together stakeholders in partner violence and victim services, batterers’ programs, fatherhood programs, and parole agencies to support reentering men and the safety and well-being of their intimate partners and coparents. The project incorporated stakeholders’ insights along with the wisdom of formerly incarcerated African American men and their partners who had experienced violence in their relationships.

Safe Return produced a set of culturally specific and context-informed resources for (1) facilitating healing for victims, including those who have used violence themselves; (2) transforming norms related to gender, violence, and control that impair the formation of respectful and healthy relationships; (3) addressing practical reentry needs, from employment to direct communication skills; and (4) helping participants connect to trusted community resources, including partner violence services.

Safe Return: Domestic Violence and Reentry includes facilitation guides, handouts, and video vignettes for groups with affected men and women;

Building Bridges includes videos and reports for community-based organizations and public agencies implementing best practices for safe reentry; and

Journey to Healing includes video, dance and theatre resources to support healing among those who have been exposed to partner violence as children or adults.

These resources remain available to those working to end partner violence in African American communities and promote peace and healing after incarceration.

Social Conditions: Isolation and Disempowerment

Extending prior theory (Hampton et al., 2003), Multi-site Family Study participants saw abusers’ attempts at domination as shaped by their own perceived helplessness in the wider social and economic environment (particularly prison). Where general-population research has shown that abusers often isolate victims from sources of social support (Coohey, 2007; Katerndahl et al., 2013; Lanier & Maume, 2009), women in this study often already faced social isolation at the community level because of their partner’s criminalized activity and the stigmatization of incarceration. This social isolation and victims’ dependence on abusive partners’ coparenting contributions (particularly child care or small contributions to children’s day-to-day material needs) further extended their vulnerability to abuse.

Drawing on an Understanding of Context to Inform Prevention

Results of the current study point to a set of strategies that might help to prevent post-prison partner violence by addressing the contextual influences described by those who have experienced it (Table 1).

Table 1.

42776Context-responsive strategies for preventing post-prison intimate partner violence

| Context | Potential Prevention Strategies |

|---|---|

| Economic Conditions |

|

| Cognitive Conditions |

|

| Physical Conditions |

|

| Social Conditions |

|

* For example, the STRIVE Program and other economic success initiatives developed by the Center for Urban Families in Baltimore, Maryland deliver a robust combination of pre-employment services, comprehensive adjunct supports (including transportation and clothing assistance), job retention and advancement programs, and career- and family-focused case management in communities heavily affected by incarceration with guidance and leadership from individuals directly affected by incarceration and economic exclusion.

Conclusion

Advocates have long raised concerns about the potential for partner violence after a spouse’s or partner’s return from prison (Bobbitt et al., 2011; Freeland Braun, 2012; Hairston & Oliver, 2006, 2011; Oliver et al., 2006; Oliver & Hairston, 2008), but few programs or policies exist to prevent it. In an era in which experiences of incarceration and reentry—and by extension, experiences of a partner’s or coparent’s incarceration and reentry—are commonplace in low-income urban communities (Comfort, 2012; Lopez-Aguado, 2016; Sampson & Loeffler, 2010; Western & Pettit, 2010), the safety of families reuniting after a prison stay merits serious attention.

Effective partner violence prevention requires a robust understanding of the individual, family, community, and societal or policy contexts under which it arises (Assari, 2013; Shobe & Dienemann, 2008). Yet prior research has focused largely on describing individual incidents, victims, and perpetrators or (more recently) individual victimization or perpetration trajectories (Beyer et al., 2015). Further, research on the intimate partner violence experiences of incarcerated and reentering men and their partners has been scarce.

The Post-Incarceration Partner Violence Study synthesized the insights of reentering men and their partners to identify how economic, cognitive, physical, and social conditions operated across the individual, family, community, and societal levels to shape post-prison partner violence. Their insights offer a valuable starting point for future research and for considering how prevention could effectively target these conditions and effect systemic change across social-ecological levels.

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to participants in the Multi-site Family Study on Incarceration, Parenting and Partnering for sharing the experiences and insights that made our work possible. We also wish to thank the National Institutes of Justice, and particularly Senior Science Advisor Angela Moore, for supporting this research. Finally, we appreciate the anonymous peer reviewers whose feedback strengthened this work and the RTI staff who brought it to publication, including Jeri Ropero-Miller, Annie Gering, and Rebecca Brophy.