Imagine driving on narrow backroads at night while your headlights are out. You’re following a friend who has traveled this way many times before and you have to drive extremely slow and rely on her to anticipate turns so you don’t veer off the road. Doable? Yes. Efficient? Not necessarily.

That’s what it’s like for water managers to operate complex reservoir systems with few tools other than expert knowledge that has been acquired over decades. Doable? Yes. Efficient? Not necessarily. And the fewer reliable tools that water managers have, the more conservative their decision-making must be, which typically leads to an inefficient use of (often limited) supplies.

While this may have once been the acceptable norm, this system will no longer be sustainable moving forward. Increased uncertainty in precipitation patterns and volumes due to climate change combined with increased pressures on existing water management systems due to population growth will tip the scales between supply and demand. This will further reduce the margin for error that water resources managers have been operating within in the past.

The RTI Center for Water Resources (CWR) works to not only provide water resources managers with better tools, but to also provide training and long-term support so that water managers can actually use the tools we build. We provide both the car with headlights and the driver’s education course, along with roadside assistance. This allows water resources managers to not only operate more efficiently, but to also become better experts in their own systems.

Across all of CWR’s work, there is arguably no greater example of this than our partnership with the Panama Canal Authority (Autoridad del Canal de Panamà, or ACP) over the last 20 years. CWR’s work with the Canal has supported Panama’s transition from United States to Panamanian control, and hence progression toward independence and greater self-reliance.

PCC headquarters during a CWR visit in 1999. A countdown clock for the transition from U.S. to Panamanian control can be seen on the left (photo by Michael Kane).

Addressing a Need

There has always been a small margin for error when operating the Panama Canal, which “serves more than 140 maritime routes to over 80 countries,” according to the International Finance Corporation (IFC). The primary concern for operators at the ACP is predicting and controlling the depth of water in Lake Gatùn (which forms the primary channel), since it determines cargo limits for ships using the Canal.

In the early 1990’s, the Panama Canal was still under U.S. control but only a few years away from the transition to full Panamanian-ownership. The (then) Panama Canal Commission (PCC, a U.S. government agency, now ACP) was primarily dependent on the expert knowledge of staff gained over decades to operate the complex two-reservoir system of Lake Madden (now Lake Alajuela) and Lake Gatùn.

“They had spreadsheets with historical information, but they didn’t have an end-to-end system [that could predict conditions],” remembers Michael Kane, the original project manager working with the PCC and now Director of CWR.

They had spreadsheets with historical information, but they didn’t have an end-to-end system [that could predict conditions].

At that time, the PCC had to operate somewhat conservatively, relying only on historical working knowledge of the system and limited weather forecasts. Although operations were relatively smooth, there were still times when Lake Gatùn spilled water, the locks flooded, and other operational inefficiencies occurred.

Staff at the PCC heard about the hydrologic models being used by the U.S. National Weather Service (NWS) to forecast river flows. In 1996, they reached out to the International Activities Office at the NWS to request a system that could forecast inflows to the Panama Canal to improve operations. NWS in turn recommended the PCC reach out to CWR as the leading experts in hydrologic forecast systems.

CWR built both the Panama Canal River Forecast System (PANFCST) and its relationship with PCC staff simultaneously. The hydrologists at PCC were trained to both use PANFCST to forecast inflows to the Panama Canal system and to calibrate models to simulate historical flows. This type of training, particularly in model calibration, is vital for the sustainability of the system being used. If the hydrologists couldn’t trust that the models could reasonably simulate historical observed flows, how could they trust their forecasts? How could they know how to adjust the models in the future to keep them accurate and representative of the system? With a working knowledge of their new tools (i.e. not just how to turn the car on and off, but how to drive it), the hydrologists could become better experts.

The PANFCST system was officially delivered in October 1998. Even after the transition on December 31, 1999 from American to Panamanian control (and hence the transition from PCC to ACP), staff in the Meteorology and Hydrology group continued working closely with CWR staff.

“They were always interested in more training, additional support,” says Kane, who notes that one of the biggest successes during that transition was that “the people we trained stayed there and trained other people.”

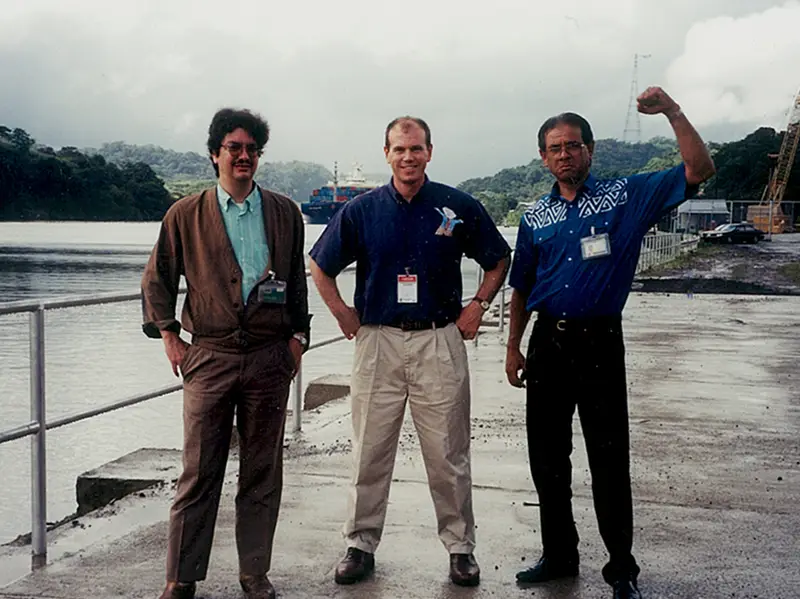

Early relationship-building between CWR and the ACP: Michael Kane visiting the Panama Canal with Manuel Vilar and Modesto Echevers, two of the first hydrologists trained to use and calibrate PANFCST (photo by Jay Day).

Seeing the Road

Another important impact of CWR’s initial work was that PANFCST opened the ACP’s eyes to ideas on how they could better operate their system. As their operations became more efficient, they began thinking of new ways that they could further improve the Panama Canal. The ACP realized that they could use PANFCST not just to forecast the hydrology and reservoir operations, but to also test future scenarios of new infrastructure.

As part of the initial build of PANFCST, CWR had developed a new reservoir model that could simulate operations at Lake Madden and Lake Gatùn in tandem, known as the Joint Reservoir Operation model, or RES-J. In fact, RES-J was adopted by the NWS as the de facto tool for modeling reservoirs in the U.S. and is now used all over the world in a variety of river forecast systems.

Staff at the ACP saw that they could use RES-J to test the system’s response to altering infrastructure and operations. Kane remembers, “They began asking, ‘What if we change things? What if we made the locks more efficient and they use less water? What if we built a third set of locks?’”

They began asking, ‘What if we change things? What if we made the locks more efficient and they use less water? What if we built a third set of locks?

ACP’s hydrologists traveled to the U.S. to test their questions with CWR staff by modifying the modeling system and using a long record of historical data. Within PANFCST, they added new reservoirs and changed how the locks used water. By the time they returned to Panama, they realized that the hydrology of the Panama Canal basin could supply enough water to support the construction and operation of a third set of locks.

That was in 2002. The ACP used the analysis completed through the scenario testing to make the decision to build the third set of locks, which were completed in 2016 and doubled the Panama Canal’s cargo capacity.

Continuing a Partnership that Fosters Local Expertise

Today, the Panama Canal has completely transitioned to Panamanian control. The ACP completed its own expansion project to add the third locks, which was a huge boost to the already-important contribution of the Canal to the country’s economy. Ships are able to line up for passage through the Panama Canal one month in advance due to the reliability of the ACP’s operational forecasts. Yet our support of the ACP on their journey to self-reliance has not ended; the ACP maintains an annual support contract with CWR for assistance with various needs that arise.

Ultimately, the ACP operates the Canal independently of CWR, but chooses to continue partnering with us because of our technical expertise and long-standing relationship. The ACP can now confidently and efficiently navigate those narrow backroads at night, with CWR on speed-dial and ready to provide assistance. Kane likens CWR’s relationship with the ACP to an on-call support staff whose role is constantly evolving with the client’s needs: “We like helping them solve their own problems.”

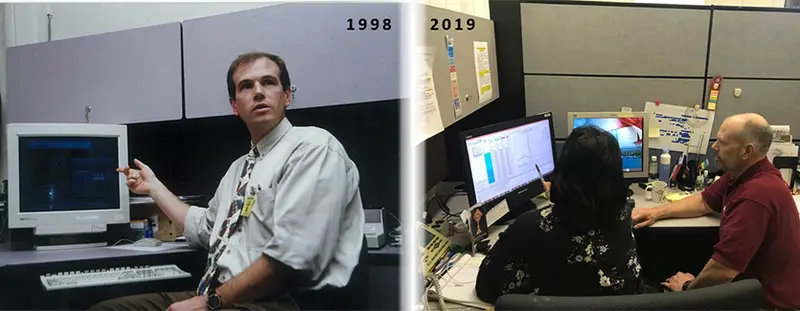

The CWR-ACP relationship spans 20 years. Left: Michael Kane giving a demonstration of the first PANFCST system to the Canal administrator in 1998 (photo by PCC). Right: Tamara Muñoz, a hydrologist in the Water Resources Section at the ACP, reviewing a recent forecast with Michael Kane in 2019 (photo by Mark Woodbury).

Learn more about CWR projects, experts, sectors, services, and tools.

Insight post header image photo credit: Autoridad del Canal de Panamà (ACP).