Initial Lessons from Ask Suicide-Screening Questions Implementation in Indian Country

Pamela Sparks, LCSW, LADC

Behavioral Health Supervisor at Clinton Indian Health Center

American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) communities experience the fastest growing rates of suicide in the United States. Death by suicide is the second leading cause of death for non-Hispanic AI/AN individuals. Efforts to address this disproportionately high rate of death by suicide among AI/AN individuals are being implemented by nearly all Health and Human Services (HHS) agencies.

In 2024, the Indian Health Service (IHS) released a policy that required IHS federal facilities to screen patients using the Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) by September 2025. For some IHS facilities, this policy change simply involved changing the instrument that they were using to screen patients for suicide. Other facilities had to create and implement new processes, engage and train their providers, develop a system to track suicide-risk screening results, and create a process for assessing and providing treatment and care to patients who screen at high-risk for suicide.

This blog post focuses on lessons from one IHS health center to foster implementation knowledge-sharing among IHS facilities. It aims to add to the implementation lessons that are starting to emerge as IHS facilities adopt this new policy.

Located in Western Oklahoma (Figure 1), Clinton IHS Health Center provides health care services to the people enrolled in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes as well as other AI/AN communities in Oklahoma. The Clinton IHS Health Center was originally established in 1955 with a modern facility opening in 2007. The health center offers a vast array of ambulatory care services including behavioral health, chiropractic, dental, laboratory, nephrology, orthopedics, pharmacy, and physical therapy.

Starting in July 2025, Clinton staff began screening patients using the ASQ, and the Patient Health Questionnaire- 9 (PHQ-9) or the PHQ-A (PHQ-9 modified for Adolescents). These screenings are administered to patients every 90 days by providers across the health center including those that do not provide behavioral health services. In the first month (July 2025), 2,109 Clinton health center patients were screened using the ASQ. To reach this screening milestone, Clinton behavioral health staff used three main implementation strategies:

The National Suicide Prevention office at IHS provided all facilities with training materials and resources to help implement the ASQ. These trainings offer skill-building techniques to select health center staff who are then expected to train their colleagues. Specifically, this train-the-trainer approach relied on the notion that federal IHS facilities already had an integrated behavioral and physical health approach in place operating smoothly.

However, like many IHS facilities, Clinton had not yet managed to successfully integrate its behavioral and physical health services. Instead, Clinton customized the IHS train-the-trainer materials so that each provider type had its own set of training materials. These materials explained the importance of screening in terms that were relevant to each type of provider and introduced the benefits of integrating behavioral and physical health care and how this integration can take place. Also, behavioral health staff meet with physical health staff every other week to discuss implementation progress, problem-solve any challenges that arise, and support one another.

The Ask Suicide-Screening Questions (ASQ) is a screening tool designed to determine whether a patient is at high, moderate, or low risk of suicide. The ASQ toolkit was developed by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) in 2008 and validated among adults in 2014. Patients are typically screened by health center staff using the ASQ toolkit and those patients with positive screening results are referred to a behavioral health provider for an assessment to gauge imminentness and intensity of their suicide risk.

Recognizing that the nuances and confusion that the separate screening and assessment processes generated among non-behavioral health providers, the leadership at Clinton health center decided to add an additional step in the process and rename the overall assessment process.

At Clinton, the new process entailed patients first completing the ASQ on their own. Providers then review the responses verbally with patients and cross-check them against the patient’s medical record. This extra review step allows for both validation and additional screening by the provider. One provider shared:

“I had an adolescent complete the suicide screening indicating that in the past few weeks, [the patient] had not wished [she] were dead. Yet, when I reviewed her record, she had had an emergency room visit for suicidal thoughts earlier in the month. When I asked her about the ER visit, she began to reflect on how she was doing honestly and we were able to obtain a more accurate screening.”

Additionally, to clearly distinguish screening from assessment, the Clinton health center began referring to the assessment as a behavioral health evaluation. This change helps ensure that when providers document a screening, they do not unintentionally indicate that an assessment also occurred. Also, further evaluation is always conducted by a behavioral health provider so if a patient’s EHR indicates that assessment took place and the note was not documented by a behavioral health provider, the system will flag that only behavioral health providers can conduct assessments or follow-up suicide-risk evaluations.

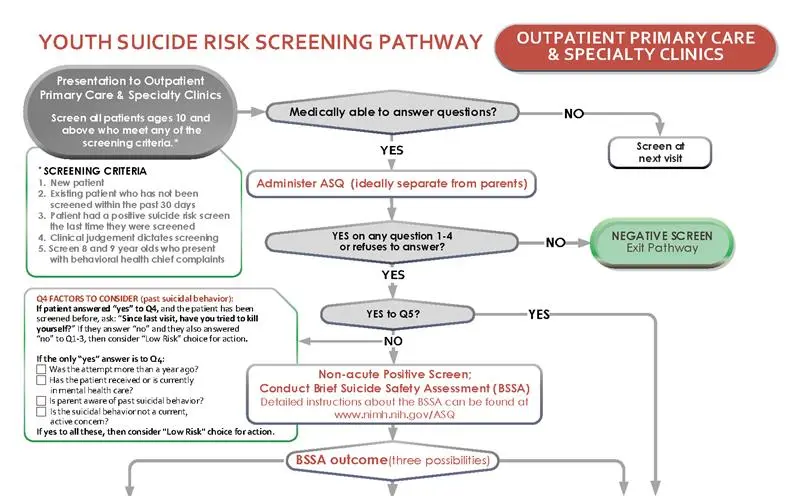

Since the 1980s, clinical pathway models have been used as a quality improvement tool among health care leadership. They are pictorial guides that outline the clinical processes. Figure 2 provides an example of a clinical care pathway. For suicide screening, this type of model would entail outlining which staff are responsible for conducting the screening, how staff will proceed if a patient screens positive or negative, and who handles the next steps in the pathway. These pictorial guides serve as guidance documents for staff and as critical documentation of the health center’s suicide screening processes and procedures. The development of a clinical care pathway model often benefits from staff input. For example, at the Clinton health center, the behavioral health director met with staff that were listed in each step of the clinical care pathway to discuss their role in the model, whether they felt comfortable serving in the identified role, and what questions they had about their role. By working through this model with staff, the director was able to obtain staff buy-in and allowed the clinical staff to provide critical feedback on the process as it was being developed.

As IHS facilities work to address this policy change and adopt the ASQ screening toolkit as part of their patient processes, building on lessons that other facilities have learned is beneficial. IHS' Clinton Health Center offers a valuable model of ASQ implementation from which other IHS facilities can learn. Ultimately, this policy has the potential to save lives by identifying suicide risk earlier, improving care coordination, and expanding access to timely mental health support across AI/AN communities.