Evaluating the potential effects of reformulation and pricing of packaged foods on child and adolescent diet quality

Almost one in five children and adolescents in the United States are obese. While the rate of increase has slowed in recent years, the prevalence remains unacceptably high. A substantial portion of calories consumed by children and adolescents currently comes from packaged foods and sugar-sweetened beverages. While some of these foods are consumed as part of a healthy meal, many others are not.

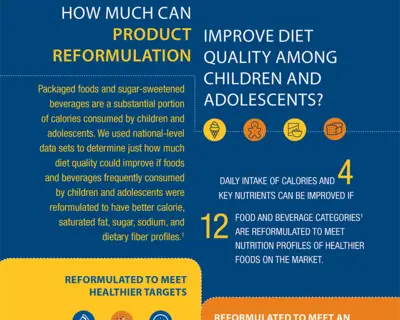

Food reformulation offers a promising avenue through which to impact childhood obesity by improving dietary quality. Food manufacturers already reformulate foods in response to external drivers like consumer demand, voluntary industry initiatives, and government regulations aimed at improving the nutrient profiles of foods. Because the potential benefits of reformulation can be reaped even in the absence of people or households altering their food purchasing behaviors, it offers a different mechanism to affect diet quality and childhood obesity while simultaneously complementing efforts aimed at individual behavior change.

Food reformulation offers a promising avenue through which to impact childhood obesity by improving dietary quality.

We partnered with researchers at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service to determine the extent to which reformulation of foods frequently consumed by children and adolescents could improve the healthfulness of those foods and, subsequently, diet quality. Because reformulation could raise the costs of manufacturing foods, we also assessed whether healthier foods have higher average prices than less healthy foods.

Using Multiple Datasets to Obtain a Comprehensive Understanding

We used National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) dietary recall data from 2013 to 2014 to identify food and beverage categories most frequently consumed by children and adolescents and to calculate average consumption levels of calories and four selected nutrients—saturated fat, total sugars, sodium, and dietary fiber. We then used store scanner data from 2014 matched with nutrition data at the barcode level to calculate nutrient levels of 12 categories of packaged foods and beverages. Using 2014 household scanner data, we calculated quantities of selected foods and beverages purchased by households with children and adolescents in the United States. Then, we used the Guiding Stars® database of 1-, 2- and 3-star products available on the market to calculate average levels of nutrients in foods that meet an existing nutrition standard to use as target calorie and nutrient levels in simulations. Next, we simulated effects of potential improvements in these 12 categories on dietary quality. The simulation assumed that purchase amounts were the same as those observed in 2014 among households with children and adolescents and that only the nutrient levels changed.

Finally, we used the Children’s Food and Beverage Advertising Initiative (CFBAI) nutrition criteria specific to different food categories to assign foods from six product categories as more or less healthy, and then calculated differences in prices of healthier versus less healthy foods.

Changing Diets through Changing the Food Supply, Though it May Come at a Cost

We focused on 12 categories of packaged foods and beverages that were identified as frequently consumed by children and adolescents: cookies and brownies, crackers, fruit drinks, granola and cereal bars, ice cream, macaroni and cheese mixes, pizza, potato chips, ready-to-eat cereals, tortilla and other chips, yeast breads, and yogurt. The simulation results showed minimal changes for calories and sodium, but that daily intake of saturated fat could decrease by 4 percent and sugar consumption by 5 percent, if food products shifted to average 1-star nutrition criteria. Dietary fiber consumption could increase by 11 percent relative to current intake. Further analysis showed that average daily intake could change even more substantially if food products were reformulated to meet the maximum star rating for product categories. Caloric intake could decline by 4 percent, saturated fat by 6 percent, sugar by 9 percent, and sodium by 4 percent, while dietary fiber could increase by 14 percent.

However, if reformulation leads to higher prices for healthier foods, the effects of reformulation on diet quality could be dampened. Healthier versions of crackers, tortilla and other chips, yeast breads, and yogurts cost, on average, between 3 and 12 cents more per serving than their less healthy counterparts. Healthier ready-to-eat cereals came in at 1 cent less per serving than less healthy versions, while healthier cereal bars cost 34 cents less per serving than bars with less healthy profiles.

Our results show it is possible to improve dietary quality for households with children and adolescents by reformulating just 12 frequently-consumed foods using nutrition standards that already exist. The impact on diet quality can be achieved by changing the food supply, which benefits all consumers—not just those who are nutritionally aware—and can complement efforts to change eating behavior.

Our results show it is possible to improve dietary quality for households with children and adolescents by reformulating just 12 frequently-consumed foods using nutrition standards that already exist.

These results are particularly encouraging given the interest some governments have shown in using reformulation as a tool to reduce childhood obesity, food companies’ increasing interest in participating in voluntary industry initiatives aimed at improving the healthfulness of foods, and upcoming changes to the Nutrition Facts label set to take effect in 2020. However, if reformulation leads to substantial changes in the taste or price of foods, improvements to dietary quality may be more limited.

This research was funded in part by the intramural research program of the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. The findings and conclusions in this publication have not been formally disseminated by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and should not be constructed to represent any Agency determination or policy.

- Healthy Eating Research

- a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation