This piece was originally published by Cancer Research UK.

Globally, cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women.

It’s unusual, as cancers go, in that 99% of cases worldwide are caused by a virus called human papillomavirus (HPV). In many countries around the world, people are given a vaccine to prevent HPV at an early age.

You may have seen this vaccine in the news recently, when ground-breaking research proved, for the very first time, that the UK’s HPV vaccination programme reduced cervical cancer cases by almost 90% in women in their 20s who were offered it at age 12 to 13.

The mounting evidence continues to point us in one direction – that cervical cancer is highly preventable. But despite this, across the globe, someone dies every 2 minutes from the disease.

In 2020 alone, it’s estimated that over 600,000 women worldwide were diagnosed with the disease, and over 340,000 died because of it.

Dr Ishu Kataria is one of the people trying to change those figures. Kataria is a senior public health researcher at the Research Triangle Institute (RTI) International Center for Global Noncommunicable Diseases. In addition, she works with the World Health Organization to help prevent the spread of infections like HPV around the world.

Why is an HPV vaccination programme so important?

HPV is extremely common, infecting the skin and the cells lining the inside of the body. Most of the time the HPV infection doesn’t cause any problems and clears up by itself. It’s only when certain types, or strains, of the virus can’t be fought off by the body’s immune system, that it can cause damage that can lead to cancer.

HPV vaccines offered in the UK protect against the main cancer-causing strains of the virus: HPV 16 and 18.

“Because HPV is a major cause of cervical cancer, a vaccine against HPV will help prevent a woman from getting cervical cancer in the future, which is actually a disease that can become fatal, particularly if it progresses to later stages.” explains Kataria. “We see a lot of deaths that happen across the globe due to cervical cancer. But the vaccine can actually prevent most cases of the disease if we give it to girls before they are exposed to the virus.”

Previous results had confirmed that HPV vaccination is effective in preventing HPV infection, genital warts and precancerous cell changes in the cervix. Now, evidence continues to indicate that the HPV vaccine is highly effective at preventing cervical cancer.

What’s more, a year ago, on 17th November 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced an ambitious plan: to create a ‘cervical cancer-free future’. A strategy which hopes to see cervical cancer become the first cancer to be ‘eliminated as a health problem’ on a global scale.

To get there, WHO has devised the 90-70-90 targets to ensure 90% of girls are vaccinated, 70% of women are screened and 90% of women with pre-cancerous cervical cell changes receive treatment. These are milestones to be achieved by 2030 in order to make sure the world is on the right track to dramatically reducing cervical cancer burden.

A year on, and the COVID-19 pandemic has slowed down progress for the WHO’s plan. Considerable steps forward have been made with the launch of new guidelines to inform cervical screening and several trials exploring the use of single dose HPV vaccines. But despite these advances, and the slowly decreasing trends in cervical cancer rates globally, this isn’t equal around the world. Cervical cancer still has some of the highest case numbers of all cancer types, with some countries seeing an increase in incidence rates in the last two decades. Cervical cancer remains a substantial health problem for women globally.

In India, cervical cancer it is the third most common cancer and accounts for the second highest number of cancer deaths in the country. In fact, almost a quarter (23%) of cervical cancer cases and deaths around the world are estimated to occur in India. People are screened for cervical cancer but right now – in the country that contains almost a fifth (18%) of the global population – there’s no consistent national HPV vaccination programme.

This is where Kataria and her team have stepped in. They’re embarking on a unique research project, funded by Cancer Research UK, to assess the feasibility of introducing the HPV vaccine into India’s National Immunisation Programme.

“What our project is aiming to do is to understand what the level of vaccine preparedness is and help to develop the evidence to encourage state Governments who are intending to introduce the HPV vaccine.”

The scale of public health in India

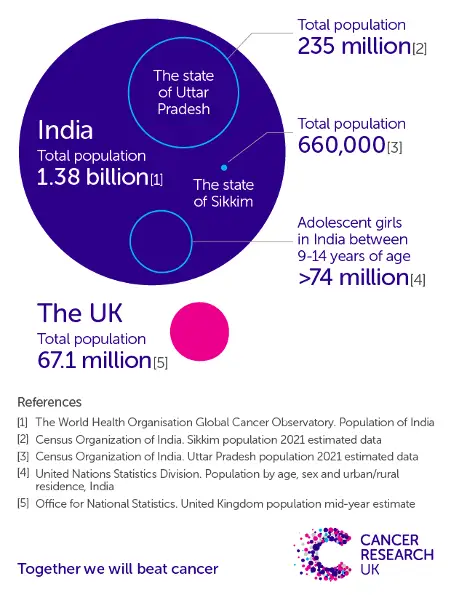

In a country as large as India, it’s an ambitious goal. India is around 13 times larger than the UK, with a population that’s about 20 times greater, at well over 1 billion people.

India’s divided up into 28 different states – some of them small, like Sikkim (just a bit more than the City of Glasgow), and some very big, like Uttar Pradesh (similar to the combined population of the UK, Ireland, France, Spain, Portugal and Poland

Copy this link and share our graphic. Credit: Cancer Research UK.

Unlike the UK, where the majority of healthcare services are provided centrally through the NHS, the different states in India control their healthcare and are guided by the national Government. This means that the administration of the HPV vaccine can vary between states – in some states it’s delivered routinely, while in others, the vaccine programme doesn’t exist.

Because HPV tends to be sexually transmitted, the vaccine is given to adolescent girls between the ages of 9 –14. According to the most recent census, there are over 74 million girls in India. For context, the total population of Britain and Ireland stands just shy at around 72 million people.

Reaching all 74 million girls will be no easy feat, but Kataria and her team are ready to take on the challenge.

Looking at the history books

Since 2008, 2 HPV vaccines have been made available in India, a quadrivalent vaccine (Gardasil), which protects against 4 strains of HPV, and a bivalent vaccine (Ceravix), which protects against 2. Both of these vaccine offer protection against the high risk strains HPV 16 and 18. But just because the vaccines are available, it doesn’t mean they are accessible.

“Generally, the HPV vaccine is available through a mode which is in a private fashion,” explains Kataria, “so it’s not affordable for everyone.”

However, price isn’t the only obstacle.

In 2009, 2 states launched a project to examine the feasibility and acceptability of integrating a vaccination programme into public health services. “But what happened was there were some health issues at the time that were wrongly attributed to HPV vaccination,” explains Kataria. “The trial was stopped and it created a lot of mistrust among the population.”

Since then, 3 states in India have successfully implemented HPV vaccination programmes. Although this is good progress, Kataria emphasises that it’s essential that all adolescent girls have access to the vaccine.

The project so far

Kataria and her team are really trying to understand what needs to be done to ensure all adolescent girls have access.

This means speaking to people at national, state and district level Government, as well as people within charities and government-associated organisations. From these conversations, the team will develop recommendations and key messages that advocates and policymakers can use to call for nationwide access to HPV vaccinations.

The people that the team have spoken to so far are all in agreement that a national vaccine programme would be the best way to administer the vaccine. “Historically, immunisation is something that India has sorted out pretty well, and we get good coverage around it.

“And because of COVID-19, it has given the Government confidence that they can actually vaccinate people that are not part of the usual routine immunisation groups of infants and children.”

Kataria explains that the COVID-19 vaccination programme has further improved the infrastructure, making it easier to introduce new vaccines.

So, what’s the catch?

Challenges at every level

Kataria describes how there are challenges, or barriers, to the expansion of an HPV vaccination programme, at each level.

The first obstacle to overcome is personal.

“I think one of the key things is that with the way we function as a society in India, the adolescent girls don’t have an entirely independent choice about HPV vaccination.”

Kataria explains that often the choice ultimately lies with the parents, who she calls the decision makers. “And a lot of people will have questions,” she says. “And since these questions will be related to adolescent girls, they may be based around sexual implications as people may think it can lead to promiscuity.

“Experts have said that even more than the logistics of the vaccination programme itself, the communication and social mobilisation strategy will be key in all this setup.”

When interviewing a state immunisation officer in one of the North East states, Kataria heard how there would need to be people, including the state organisation officers, medical professionals and technical experts who could go as a team and hold a session to clear any doubts for the school authorities and local community to feel secure with the vaccination programme.

For Kataria, it helped to reiterate just how important communication is going to be. “It’s something that needs to be really well done – myths and misconceptions that people will have about the vaccine is also a key barrier that we need to overcome.”

But even if the young women who are eligible for the vaccine, and their families, consent to the vaccine, the puzzle isn’t complete.

The next hurdle is cost. “We were actually told by a lot of health care providers that they themselves wouldn’t recommend the vaccine, because they think a lot of people can’t afford it.”

However, there may be a solution on the horizon, as a vaccine produced in India is expected to be approved in the near future. This could provide a more cost-effective alternative to the other vaccines currently available.

A vaccine produced locally could also address hesitancy at a Government level, Kataria comments. “The Government have a large focus on indigenous vaccines. We’ve seen that with COVID-19, a vaccine has been developed indigenously in the country and is being administered to the population successfully, safely and effectively.”

When this HPV vaccine is launched into production, with a significant cut in the cost, Kataria notes that there will be a surge in the motivation of the Government of India to integrate the HPV vaccine into the National Immunisation Programme.

Kataria adds that there are lots of valuable lessons to learn from the states that already have an immunisation programme.

“Both states of Sikkim and Punjab use schools as a vehicle to initiate vaccination. And they have found this strategy very successful, because there is an opportunity to get teachers and parents involved. The students place a lot of trust in teachers, so both these states have seen very high uptake through school-based vaccinations, and this method will need to be prioritised by other states as well.”

Looking forward

There’s still a way to go before any results of Kataria’s research project can be published, turned into policy briefs, and discussed with advocates and policymakers, but the team are gathering invaluable information every day.

And with the challenges that exist at each level, the solutions seem to point in one direction – that working together to get HPV vaccination included in the National Immunisation Programme would bring India closer to ensuring that cervical cancer is ‘eliminated’.

Despite the scale of the challenges, Kataria remains wholly optimistic. “India will definitely start HPV vaccination through its national immunisation programme. And we will have the girls who are in the eligible age category getting vaccinated. That is what I hope. And that is what I dream, and I’m quite optimistic that that will eventually happen.”