January 24 is the International Day of Education—a day of celebration of the role of education for peace and development.

Education is critical for countries to meet their human capital development goals: it provides people with knowledge, it helps them better themselves and understand the world around them, and ultimately paves a way for their employment and providing a livelihood for their families. Consequently, increasing and sustaining access to quality education, including by ensuring schools are functional, teachers are present, and educational materials are available, remains a major priority for communities, countries, and a range of global stakeholders. Yet, a commonly overlooked aspect is how education can be impacted by various extrinsic factors—and good health is chief among them. In lower- and-middle-income countries, specifically in sub-Saharan Africa, one disease in particular continues to have an outsized impact on childhood health: malaria.

Malaria’s impact on childhood health

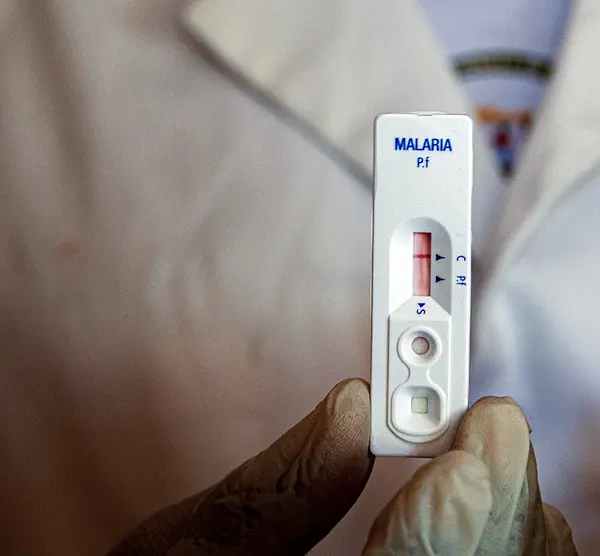

Malaria is among the leading causes of illness and death among children in sub-Saharan Africa. Transmitted by a mosquito bite, symptoms range from shivering and chills followed by a high fever to headache, nausea and vomiting, muscle or joint pain, and general fatigue. In its more severe form, malaria can result in seizures, organ failure, coma, and death. Because of their low anti-malarial immunity, pre-school age children (generally under 5 years of age) are at greatest risk of severe malaria and malaria-related mortality. While less likely to experience severe malaria and malaria-mortality compared to pre-school age children, school-age children suffer from clinical malaria (an acute episode of illness prompting treatment seeking) and chronic infections, both of which are associated with anemia.

The link between malaria and learning, cognition, and education outcomes

In both pre-school and school-age children, malaria can negatively impact learning and education outcomes. For example, malaria symptoms, including fever, anemia, and myalgia—especially when recurring repeatedly in high transmission areas—affect concentration and general ability to absorb information. In school-age children, the disease leads to absenteeism from school, hindering the continuity of the learning process. Additionally, the cognitive impairments associated with malaria may compromise students' ability to actively participate in their studies, thereby contributing to a potential decline in academic performance. Addressing malaria in these age groups is crucial for fostering a conducive environment for learning and promoting overall educational success.

In the past decade, several malaria interventions, specifically seasonal malaria chemoprevention and insecticide-treated bed nets, have targeted preschool- and, to a degree, school-age children. Both have contributed to large reductions in malaria prevalence and incidence across sub-Saharan Africa. And of course now, we anticipate that the large-scale roll out of the malaria vaccine may have a similar impact.

While some studies suggest decreasing malaria burden leads to improved cognition and education, the evidence base is inconclusive, largely due to reliance on brief interventions and metrics limited to sustained attention and routine classroom tests as indicators of cognition and educational outcomes, respectively. No prior studies have evaluated the impact of malaria control interventions at scale on cognition or education.

Understanding the impact of health interventions on cognition and education is central to estimating the full societal impact of disease control programs and determining whether health interventions may contribute to achieving Sustainable Development Goal 4 (Quality Education).

We hypothesize that if pre-school and school-age children continuously receive seasonal malaria chemoprevention, have benefitted from population-level malaria interventions such as bednets, or in the future the malaria vaccine, then they experience fewer episodes of clinical malaria leading to fewer school absences and have less chronic parasitemia, leading to improved wellness and concentration, which then increases their ability to learn and attain higher education outcomes, thereby positively impacting long-term child development outcomes.

Could reducing the malaria burden have an education dividend?

A newly launched collaborative research study between the University of Maryland, the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and RTI is striving to answer this question. The study is one of seven independent research efforts funded by RTI in 2024 to address key international development challenges—part of our mission to improve the human condition by turning knowledge into practice.

Using an existing nationally representative survey and large-scale programmatic malaria and education intervention data, we will assess whether interventions that reduce malaria burden in pre-school and school-age children impact learning and educational outcomes and what the most useful metrics for measuring these outcomes are.

Specifically, we will conduct three types of analyses, the results of which, combined, we hope will answer these research questions:

- What is the population-level evidence that malaria interventions at scale are associated with improved early childhood development outcomes?

- What is the evidence that malaria interventions at scale are associated with improved learning and education outcomes?

- What is the individual-level evidence that school-age children who are protected from malaria learn better and have greater education outcomes than those who are not?

Should our research show that malaria burden reduction efforts indeed lead to better learning and education outcomes, more intensive investment and efforts for cross-sectoral programming across the health and education sectors would be warranted to not only ensure children have access to education, but that they are also set up—in terms of their overall health—to succeed in absorbing information and knowledge, thereby maximizing communities’ education and human capital.